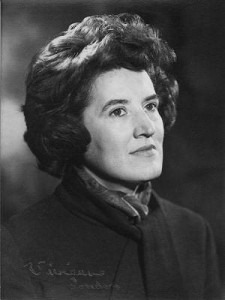

Joyce Hatto

Credit: http://www.bach-cantatas.com/

Occasionally when I’m at a concert, I hear people remark that the performance “wasn’t like the CD”. These comments seem tinged with disappointment, suggesting that the listeners were expecting a pristine performance identical to the high-quality CD on their bookshelf at home.

I love the excitement of live music – and the whole concert-going experience, from the moment I arrive at the venue and join the throng of people in the foyer or bar, the air full of that eager hum of expectancy, and all the little “rituals” of concert-going: meeting friends, discussing the music we’re about to hear, slipping into the plush seats. Then the house lights dim and the adventure that is a live performance begins. Each performance is different, and it is this very uniqueness that makes live music so special.

These days it is almost de rigeur to find CDs by the featured artist for sale at the concert. For many people, these recordings are a way of keeping the memory of the concert alive, purchasing a “souvenir” to take home, or another recording to add to a cherished collection.

At the turn of the twentieth century, at a time when recordings were relatively scarce, the activity of concert going was confined to a relatively small minority of cultured people (the Proms were conceived to bring classical music to a wider audience and to make music more accessible) and the symphonies of Beethoven, for example, could be heard only in a select few concert halls. And because of the scarcity of recordings, performers enjoyed much more freedom in the way they rehearsed, presented and performed the music. For example, encores were often given between the movements of a symphony: audiences demanded encores, and received them, and there was nearly always applause between movements (a cardinal sin of concert etiquette these days). With few or no recordings to bolster their career, performers made their living from, well, performing.

Since the middle of the twentieth century, recording technology has grown ever more sophisticated, allowing artists and orchestras to create performances which are almost alien to the performance in the concert hall. Alongside this, a certain “globalisation” of sound has emerged, if all the rough edges and distinctive national traits of earlier performers and performances have been smoothed out, and even so-called “live” performances are subject to editing and touching up. (‘Hattogate’ offered us some interesting insights into the craft, and craftiness, of the editor.) Russian pianist Grigory Sokolov insists that all his recordings (and he has made relatively few during his long career) are genuinely live – one concert, one take, ensuring that no two recordings are ever the same and retaining, as far as possible, the spontaneity of his live performances.

With the rise of high-quality recordings, and the ease with which they could be obtained, performers, ensembles and orchestras were forced to abandon the rather laissez-faire attitude to rehearsing and performing that had existed in an earlier age – because now they had quality recordings to provide them with feedback. Now they could assess not only their own playing but also compare performances of the same works by other performers around the world, and certain recordings by certain orchestras/conductors/soloists have become regarded as the benchmark against which other recordings and performances are measured. This standardisation of sound meant that audiences demanded the same high-quality sound in live performances, and performers have been forced to adopt higher standards of technical facility, accuracy, consistency of presentation and expressive focus that were unknown in the first half of the twentieth century.

This, of course, is no bad thing, and the quality of music one can hear on any given night in any concert hall around the world these days is testament to the high standards performers now set themselves, and similarly high standards demanded by audiences and consumers of quality recordings. But it has also led, in my opinion, to a desire by certain audience members to expect to hear an exact recreation of a recording in a live performance – something which is, of course, impossible, for no two live performances are ever the same.

Recordings and live performances are two very separate entities, and should be regarded as such. Many classical performers find the recording studio a difficult place to be as it robs them of the spontaneity that comes from performing to an audience. Curiously, many performers also find recording more nerve-wracking than live performing, even though they have the “safety net” of the editing process to remove errors and inconsistencies. Compare this with Glenn Gould who resented “the one-timeness, or the non-take-twoness, of the live concert experience”. He famously stopped giving live concerts in 1964, believing his artistry was better served by committing his music to recordings.

Now, with so much technology available to manipulate sound, classical performers working with skilled producers and editors are able to produce more experimental or “hyper” recordings – something I think Glenn Gould would have enjoyed, given his interest in the recording process and the ability to make creative choices by selecting particular “takes” for inclusion in a recording.

Hyper-production of Debussy’s La Cathedrale Engloutie.

With the increasing popularity and ease of access of platforms such as YouTube and music streaming services, it is now possible to hear vintage recordings of composers performing their own works (there are wonderful archive recordings of Rachmaninoff and Ravel playing their own piano music, for example) and to recapture the sounds of an earlier age.

Further reading

Performing Music in the Age of Recording – Robert Philip