Chausson in 1885

Robert Casadesus (1899-1972) was far better known as a pianist than as a composer, but in his compositions, we find an interesting side view on this most French of French pianists.

In his 1954 work, Homage à Chausson, Casadesus paid honor to Amédée-Ernest Chausson (1855-1899), a French composer who had died 2 months after Casadesus was born, on the centenary of his birth. Chausson was a French composer who came to music late. After completing his law degree for his father, he started classes at the Paris Conservatoire and was recognized by his teacher, Massenet, as ‘an exceptional person and a true artist.’ Coming from money, he supported music in Paris through his salons, made an important collection of paintings, and supported the Société Nationale de Musique, which not only promoted young French composers but also made performances possible of their music. The Société Nationale de Musique fought against the dominant German music of the late 19th century and promoted the ‘gospel of French music and … the works of living French composers.’

Robert Casadesus

Chausson died age 44 in a bicycle accident, just as he was coming into his own as a recognized composer, leaving behind works up to Opus 39, including an opera, a symphonic poem, a single symphony, a song cycle, and other indications of his coming greatness.

Robert Casasdesus, was one of the musical Casadesus family. His uncles, Henri (violist) and Marius Casadesus (violinist) were founders of the Société des Instruments Anciens, which functioned as a quintet of obsolete instruments, such as the viola da gamba and the viola d’amore. His aunts, Rose, Cécile, and Régina, were keyboard players. Robert’s father, Robert-Guilluame Casadesus, was also musical, writing songs, instrumental works, and a few operettas.

Robert and his wife Gaby taught at the American Conservatory at Fontainbleau, and when evacuated from France to the US during the war, was known to play duets in Princeton, NJ, with his neighbor, Albert Einstein.

As a composer, Robert was very much a non-Romantic – his music is noted for its precision and clarity. These same characteristics carried into his own performances. One writer said of his compositions: “It is music for connoisseurs, music of formal concision not devoid of passionate expression, but highly wrought, suggestive, and understated in, typically, lyrically attenuated slow movements, tender and strange, and conclusions of fastidious tumult.” And so we have his Homage to Chausson. Written for the centenary of Chausson’s birth, the work clearly notes in the score Casadesus’ intentions.

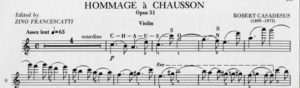

Violin part of Hommage à Chausson

Casadesus has taken care to note over the violin line Chausson’s name, although it’s a bit different from finding B-A-C-H all over the place. The letter ‘C’ is the note ‘C’, the letter ‘H’ is the note ‘B-natural’ (or ‘H’ in German), the letter ‘A’ is the note ‘A’. Ok, so far. Now ‘U’ is the note ‘E’, ‘S’ is the note ‘C’ again, ‘O’ is the note ‘G’ (which could be from ‘Sol’) and ‘N’ is the note ‘F’. Not all the letters can be directly tracked to a specific pitch, but he does what he can. However, in writing it into the score, which happens a couple of times, he makes his point clear.

This becomes an invisible bow to Chausson. The audience can probably figure out C-H-A as indicating CHAusson, but you must see the score to understand what Casadesus intended.

Casadesus: Homage à Chausson, Op. 51 (Zino Francescatti, violin; Robert Casadesus, piano)

In his precise way, Casadesus draws us a picture of his vision of Chausson – it’s not a large colourful work but more like a line-drawing – and is as fastidious as we expect.