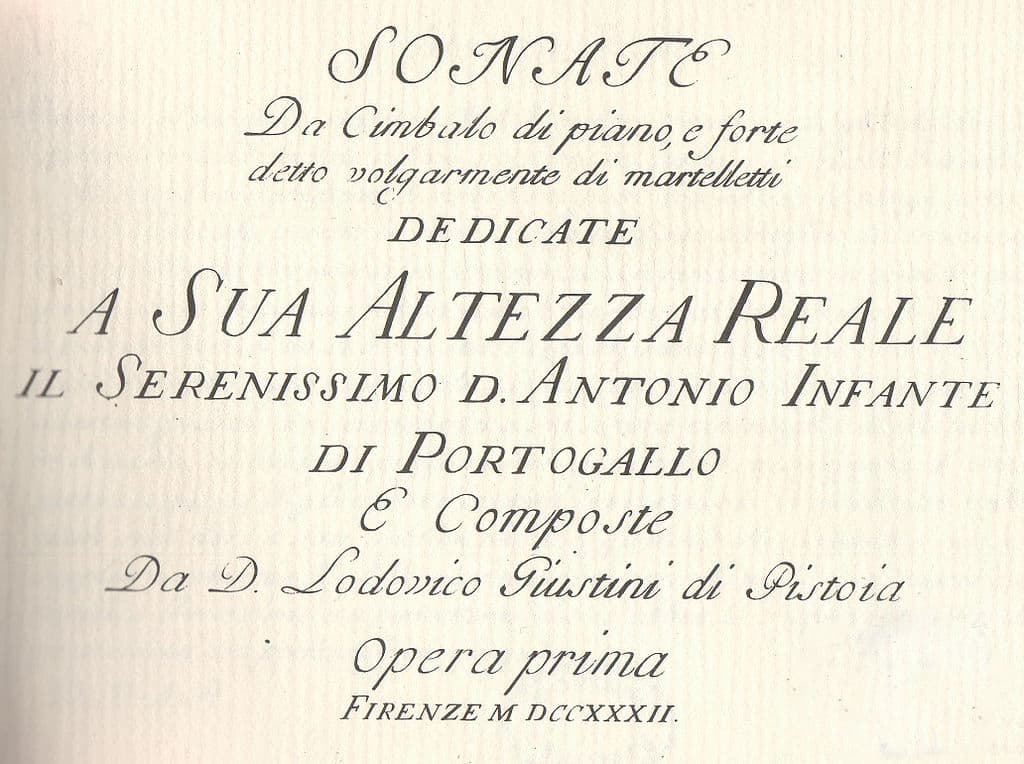

1685 was a particularly stellar year for classical music, as it saw the births of Johann Sebastian Bach, Georg Frideric Handel, and Domenico Scarlatti. However, there is at least one more composer born in 1685 who played a highly significant role in the history of music. He was the Italian composer, organist, and harpsichordist Lodovico Giustini (1685-1743), and he is primarily remembered for his 12 Sonate da cimbalo di piano e forte detto volgarmente di martelletti, Op. 1, (12 Sonatas for keyboard with loud and soft, popularly called with hammers). Supposedly published in 1732, it is the first known work to have been specifically written for the pianoforte.

Lodovico Giustini

As we all know, the invention of the piano revolutionized the music world. The new instrument offered keyboardists unhampered musical expression, making it possible to vary dynamics from gentle whispers to forceful fanfares by changing the amount of weight used when striking the keys. Giustini did not have his hand in the invention of the piano; that honor goes to the Italian instrument maker Bartolomeo Cristofori (1655-1732).

Lodovico Giustini: 12 Sonate da cimbalo di piano e forte detto volgarmenti di martelletti, Op. 1, “Sonata No. 1 in G minor” (Andrea Coen, fortepiano)

Lodovico Giustini’s 12 Sonatas for keyboard with loud and soft, popularly called with hammers

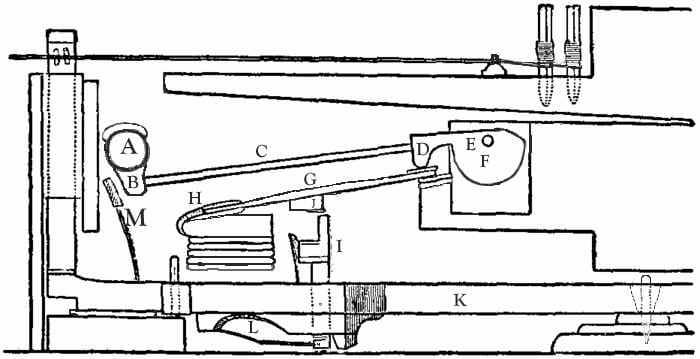

Cristofori was active at the Florentine court of Grand Prince Ferdinando de’ Medici, where he took care of an extensive instrument collection. In charge of tuning and maintaining harpsichords, Cristofori began to experiment with a hammer-action keyboard instrument capable of dynamic gradations. It is not clear when or why Cristofori started his experiments, or whether it was part of his court responsibility. We do know, however, that by 1700, a “newly invented harpsichord-like instrument with hammers and dampers having a range of four octaves” was officially described. The new instrument sparked significant interest, and it is reported that two pianos had been sold in Florence, and “another was owned by Cardinal Ottoboni in Rome.” By 1711, the Italian poet Scippione Maffei published an illustrated description of Cristofori’s piano, and a translation of that article started to circulate north of the Alps. Gottfried Silbermann’s pianos—the ones he introduced to J.S. Bach—are closely modeled on a Cristofori prototype.

Lodovico Giustini: 12 Sonate da cimbalo di piano e forte detto volgarmenti di martelletti, Op. 1, “Sonata No. 8 in A Major” (Kikuko Ogura, harpsichord)

Bartolomeo Cristofori

Only three original Cristofori pianos have survived the ravages of time. A 1720 model is housed in New York, a 1722 instrument is located in Rome, and a Leipzig collection holds a 1726 instrument. These surviving instruments “exhibit Cristofori’s tremendous ingenuity. He had grasped the technical crux of piano engineering, incorporating intermediary levers between hammer and key lever, back checks, the separation of soundboard from stress-bearing functions of the case sides and hitch pin rails, as well as many other technical subtleties.” While the harpsichord retained its place for many years to come, the “pianoforte” was slowly gaining ground. It was certainly highly prized as an object of prestige among European nobility. When soon-to-be Queen Maria Barbara left for Spain in 1729 to marry the future Ferdinand VI, she brought along her keyboard teacher Domenico Scarlatti, and as many as five pianos. Her father, the Portuguese King João V, was enamored with the new instrument, and Scarlatti also gave keyboard lessons to his younger brother Dom António de Bragança.

Lodovico Giustini: 12 Sonate da cimbalo di piano e forte detto volgarmenti di martelletti, Op. 1, “Sonata No. 5 in D Major” (Luca Guglielmi, harpsichord)

Pianoforte’s escapement action

Giustini dedicated his 12 Sonatas, supposedly published in 1732, to the Infante Dom António. The edition is prefaced in Italian by a letter of dedication written by the Benedictine monk Dom João de Seixas, “who claims to have seen the sonatas during a visit to Italy.” A recent publication describes the sonatas as “attractive compositions in early classic style that exhibit an interesting mixture of influences from Italian keyboard music, the Italian violin sonata, and French harpsichord music.” This publication attracted little interest at the time, and it is possible that the “publication of the work was meant as an honor to Giustini, representing a gesture of magnificent presentation to a royal musician, rather than an act of commercial promotion.”

Lodovico Giustini: 12 Sonate da cimbalo di piano e forte detto volgarmenti di martelletti, Op. 1, “Sonata No. 10 in F minor” (Enrico Maria Polimanti, piano)

Pianoforte invented by Cristofori, 1720

Newest research suggests that “although the only source of the sonatas is a print dated Florence, 1732, it is clear that the print could only have appeared between 1734 and 1740. It was probably disseminated out of Lisbon and not Florence.” Be that as it may, Giustini’s sonatas employ all the expressive capabilities of the new instrument, such as wide dynamic contrasts. In addition, the new instrument was not only capable of playing loudly and softly, it was also capable of playing crescendo and decrescendo, which Giustini indicated with directions such as “più forte” and “più piano.” Despite Giustini’s publication, the pianoforte only gained real traction several decades later. By the late 1780s, however, the instrument had fundamentally transformed the concert hall and the amateur music market as well.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter