The classical bilingual poet in Azerbaijani and Persian, Mirza Shafi Vazeh (1796-1852) was widely known as the “sage of Ganja,” the town of his birth. He initially studied Arabic and Persian but got expelled from school for questioning the arrogance of the religious clergy. He made a living giving calligraphy lessons, and taught Mirza Fatali Akhundov, the writer and father of Azerbaijani theater. With Akhundov’s help, Vazeh secured a teaching job in Tiflis in 1840. And he established a literary society, which attracted prominent minds from Azerbaijan, Russia, and foreign lands. And one such member was the German poet and traveler Friedrich Martin von Bodenstedt. He became Vazeh’s student in Azeri and Persian languages and literature. Significantly, he not only wrote down Vazeh’s poetry, but also upon his return to Germany, translated the poems into German.

Illustration of Mirza Shafi Vazeh

Bodenstedt’s first publication entitled “Thousand and One Days in the Orient,” provided an account of his travels in Asia, and it included a good number of Vazeh’s poems. The publication proved popular, and Bodenstedt’s publisher asked him to issue the poems in a separate volume. Bodenstedt was agreeable, and in 1851 he published a greatly expanded volume of poems under the title “Lieder des Mirza Schaffi” (The Songs of Mirza Shafi). This volume was subsequently translated into English and most other European languages with authorship erroneously attributed to Bodenstedt. Vazeh’s poems are songs of freedom, rejecting religious fanaticism, Oriental despotism, old customs, and prejudices. The characters of his imagination are associated with his personal philosophy, glorifying the joys of life and the wisdom and goodness of man.

Presumably, Anton Rubinstein (1829-1894), the Russian pianist, composer, conductor, and founder of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory stumbled upon Vazeh’s poetry during his time in Germany. He had originally spent time in Berlin in 1844, and returned for a grand concert tour to Leipzig in 1855. Ignaz Moscheles lauded his pianistic abilities and wrote, “In power and execution he is inferior to no one.” However, Rubinstein was also a highly skilled composer, and always on the lookout for new inspirations. And in the poetry of Mirza Shafi Vazeh, he found exactly that.

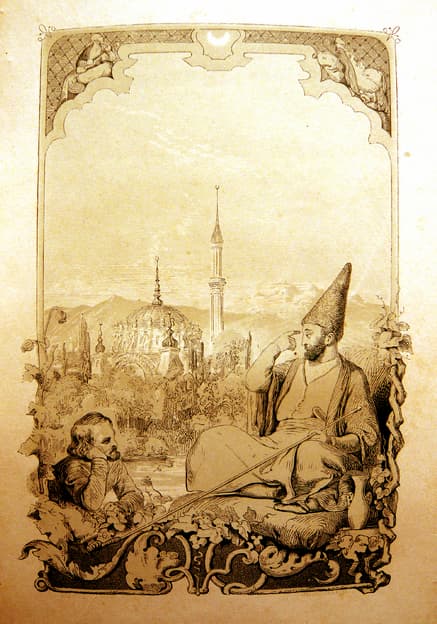

Illustration of Vazeh and Friedrich Martin von Bodenstedt

At my feet the swirling waves of the Kura River,

In the dancing bustle of the waves,

The sun smiles brightly, as do my heart and the meadow,

Oh, that it would ever remain thus!

The red Kakhetian wine sparkles in the glass,

That is filled by my beloved,

And with the wine I draw in her glances as well,

Oh, that it would ever remain thus!

The sun is sinking, already night is darkening,

But my heart, like the star of love,

Flames in the deepest darkness, in brightest splendor.

Oh, that it would ever remain thus!

Into the black sea of your eyes rushes

The raging river of my love;

Come, maiden, it is getting dark and no one can hear us!

Oh, that it would ever remain thus!

Portrait of Anton Rubinstein by Ilya Repin

In the end, Anton Rubinstein selected twelve poems and set them to music as his “12 Lieder des Mirza-Schaffy,” better known as his “Persian Love Songs.” Rubinstein was a prolific composer who composed assiduously throughout his life, but his music demonstrated none of the nationalism associated with the “Russian Five.” His Persian settings had followed the German texts from the Bodenstedt publication, and Rubinstein’s student Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky wasn’t particularly happy about that. As such, Tchaikovsky published a translation from German to Russian of Rubinstein’s “Persian Love Songs.” As Rubinstein dejectedly wrote towards the end of his life, “Russians call me German, Germans call me Russian, Jews call me a Christian, Christians a Jew. Pianists call me a composer, composers call me a pianist. The classicists think me a futurist, and the futurists call me a reactionary. My conclusion is that I am neither fish nor fowl—a pitiful individual.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Anton Rubinstein: Persian Love Songs, Op. 34