Japanese Garden

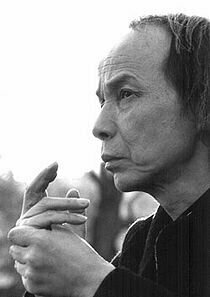

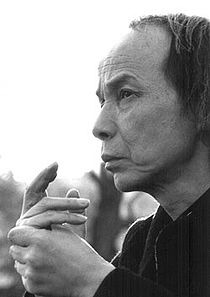

Tōru Takemitsu (1930-1996) fell in love with western classical music via American forces radio broadcasts during the post-war U.S. occupation of Japan. In fact, he “considered the radio as his first real teacher.” Almost exclusively focused on Western musical styles and genres, he even became the co-founder of an artistic group that religiously avoided all references to his native Japanese artistic tradition. “I hated everything about Japan at that time because of my experience during the war,” Takemitsu explained, as “Japanese traditional music became a symbol of my own bitterness.” He started to compose music in an explicitly modernist idiom, drawing on electro-acoustic influences and the music of his heroes Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg and Anton Webern. Takemitsu added the musical styles and techniques of Igor Stravinsky and John Cage, including controlled aleatoricisms to his compositional palate, and the world started to take notice.

Takemitsu’s philosophy about music, however, underwent a profound transformation in the early1960’s, as he consciously began to explore all types of traditional Japanese music. Fundamentally, it was a performance of Bunraku puppet theatre that inspired this change of heart. This art form was founded in Osaka in 1684 and features three different kinds of performers; the puppeteers, the chanters and the musicians. “I got a shock,” Takemitsu explained, “as I suddenly recognized that I was Japanese.” From then on, the composer opened his heart to the beauty of his homeland’s musical traditions. He experimented with different instruments, timbres and harmonies, but took his essential principles from the way Japanese gardens are constructed. Based on the idea of a “meaningful void,” this principle describes a presence, a space between objects that is full of energy. “My music is like a garden,” he writes, “I am the gardener. Listening to my music can be compared to walking through a garden and experiencing the changes in light, pattern and texture.”

Tōru Takemitsu

Credit: Wikipedia

Rather than favoring one musical tradition over the other, Takemitsu started to, as he articulated in a lecture “pay special attention to the differences between the two very different musical traditions, in a diligent attempt to bring forth the sensibilities of Japanese music that had always been within me.” Yet the true motivations and incentives for many Takemitsu compositions are not always easy to discern. For example, Rain Tree—the second of a sequence of four pieces collectively entitled “Waterscape”—is generally acknowledged to have been inspired by the title of a novel by Kenzaburo Oe. However, Takemitsu candidly admitted that he initially spied his title on the label of a can of American shaving cream, and only later endorsed the connection to Oe’s novel. Whether poetic or utilitarian, Japanese or Western, Takemitsu nevertheless evolved a highly individualistic authorial musical voice that easily transcends the implied cultural and musical duality.

Kenzaburo Oe

Credit: http://japandailypress.com/

Composed in 1981, Rain Tree is scored for two marimbas and vibraphone. However, all three performers also double on crotales—small percussion instruments consisting of tuned brass disks. Supported by atmospheric lighting indicated in the score, this composition does seemingly draw on the image of water interacting with the lush foliage of the “Rain Tree.” The first water droplets, sounding on the crotales, fall in total darkness. Gradually the marimbas add irregular rhythmic accents with the vibraphone providing an almost improvisational harmonic foundation. Soon thereafter, the marimbas establish a flexible ostinato that continues to increase in intensity. Once again joined by the vibraphone, the music steadily intensifies, however, without introducing a sense of forward momentum. In the final section, the water droplets combine to form small rivulets and streams that forcefully impact with the ground below. Dissonant clusters and the asymmetrical flow of Takemitsu’s gestures seemingly illustrate this constant shower of water that gradually narrows and eventually tapers off. Takemitsu’s integration of elements taken from an Eastern musical tradition with stylistic features borrowed from the West aptly reflects his belief that “various countries and cultures of the world have begun a journey toward the geographic and historic unity of all peoples.”

Tōru Takemitsu: Rain Tree