The medieval music theorist Guido d’Arezzo (ca. 991–992—after 1033) was a Benedictine monk who made a critical development in the history of music. His music treatise, Micrologus, was one of the most widely available medieval treatises on music.

Guido d’Arezzo

Guido first shows up in 1013 at Pomposa Abbey, near Ferrara. Pomposa is one of the most famous Benedictine monasteries of the 11th century. He first went to finish his schooling and then started teaching. His teaching methods, using staff notation, were resented by the staff, and he moved to Arezzo in 1025.

Up to this point, most music was taught by memorization. Music wasn’t written down as a reference but passed from person to person and monk to monk. Rote learning has two implications: one is that it’s easily forgotten, and the other is that it is just memorised rather than understood. This implies that if you forget something, you don’t have the ability to recreate what you learned, it just drops out of the consciousness. Using Guido’s methods, the usual 10-year training period for a cantor to 1 to 2 years.

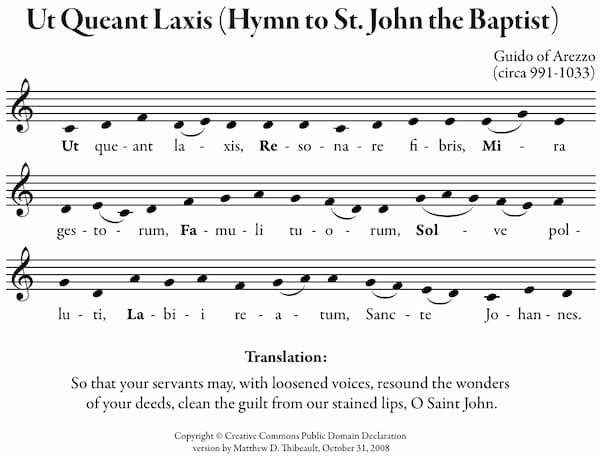

Guido had to invent everything in the move from memorisation to reading. One of his first developments was solmisation. This is the assignment of a unique syllable to a pitch. Guido used the hymn to St John the Baptist, Ut queant laxis, as his basis for each new phrase, starts up one note from the previous:

The “Ut Queant Laxis” hymn to Saint John the Baptist as used by Guido of Arezzo (Credit: Matthew Thibeault)

Guido d’Arezzo: Ut queant laxis (Christopher Gabbitas, baritone; David Miller, lute)

From this, singers were able to name pitches: ut–re–mi–fa–sol–la. A seventh pitch name, ‘si’ from the initials of Saint Ioannes (SI) or Saint John, from the last words of the hymn, filled out the scale.

Further developments changed some of the pitchnames: ‘Ut’ was changed to ‘Do’ in the seventeenth century by the theorist Giovanni Battista Doni, not just for his name but also so that the vowel would be open (oooooo versus Ew). The last note, ‘si’ was changed to ‘ti’ in the 19th century by English music educator Sarah Glover so that each syllable would have its own consonant. The final pitch names, do–re–mi–fa–sol–la–ti, are familiar to most people through the song ‘Do-Re-Me (or Do, a Deer)’ from the 1959 musical The Sound of Music.

The Sound of Music Do-Re-Mi (1965)

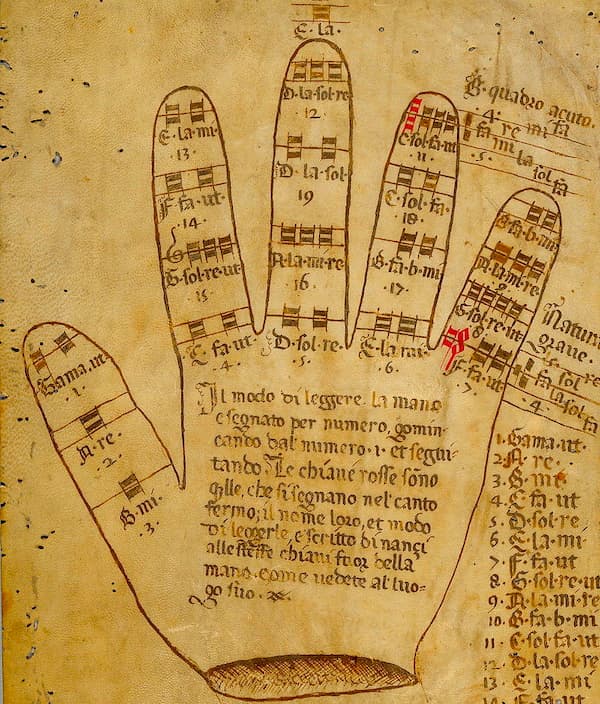

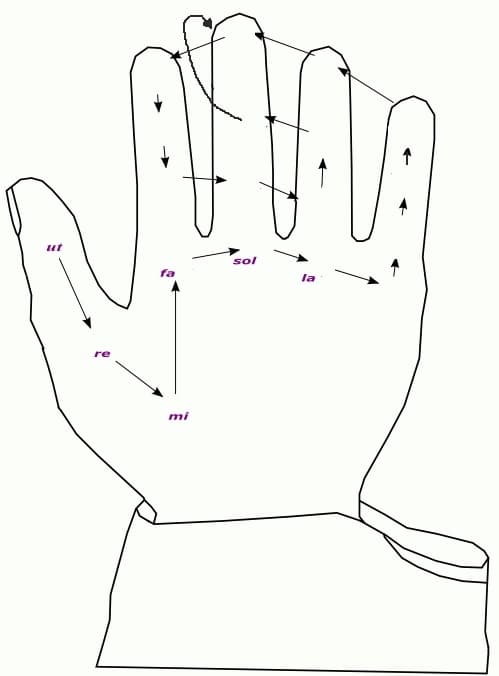

One of the teaching devices developed (but probably not finalised by Guido) was teaching through hand signals. The ‘Guidonian hand’ made it possible to indicate a pitch via a position on the hand.

Guidonian Hand, last quarter of 15th c. (Oxford University MS Canon. Liturg. 216. f.168 recto) (Bodleian Library)

However, just looking at the hand doesn’t tell you how to use it. The first three pitches start on your thumb. Using your index finger, you can point to the three places. Now, your thumb takes over, pointing at the bottom joint of your index finger, your middle finger, your ring finger, and then your pinkie.

Guidonian Hand – simplified

Then you go up the pinkie, over the tops of each of the other fingers, down the index finger, across the middle finger, go up the ring finger, over to the middle finger, and then the last note is on the back side of your hand – the nail of your middle finger.

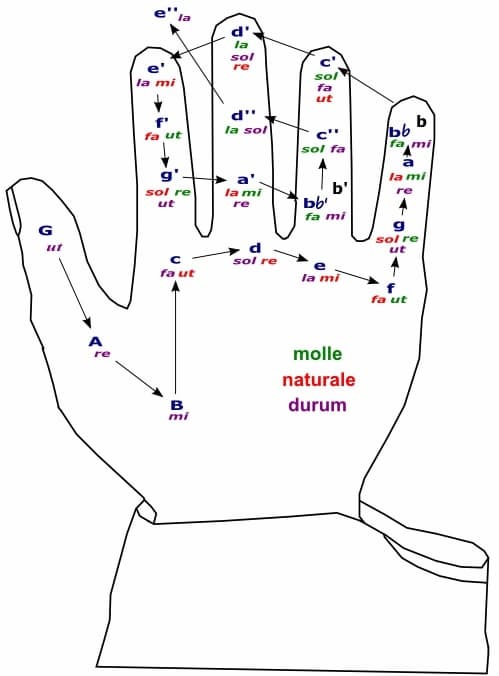

As the notation system developed, the scale was made into ‘hexachords’, i.e., six-note sections that were classified by their half-steps, which would always fall on Mi-Fa

Molle / Soft: ut-re-mi-fa-so-la (starting on G) G-A-B-C-D-E

Naturale / Natural: ut-re-mi-fa-so-la (Starting on C) C-D-E-F-G

Durum / Hard: ut-re-mi-fa-so-la (Starting on F) F-G-A-Bb-C-D

Note that in the scale starting on F, B must be shifted down to B flat to maintain the half-step. All of this could be shown on the one hand while you led the chorus with the other.

Guidonian hand with hexachords (credit: Jpascher)

For the development of staff lines, this started with the memorization. The first staff notation was a single line, simply to remind you where the pitches were in relation to each other.

Music notation with a single-line staff, 12th century (Italy)

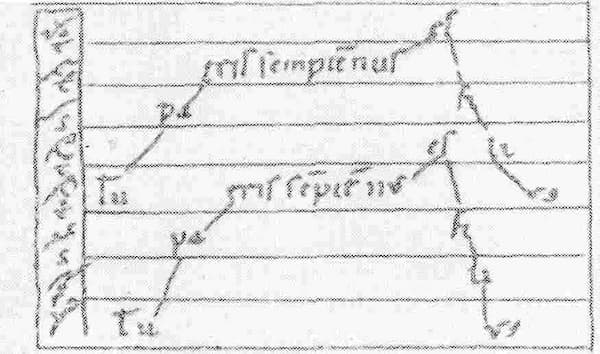

When you wanted to get more specific, more lines were used. In this example of daseian notation, the pitches are indicated on the far-left side while the text shows you the syllables and their approximate duration. The number of lines could vary from 4 to 18.

Tu patris sempiternus es filius, 9-line Daseian notation, 9th century

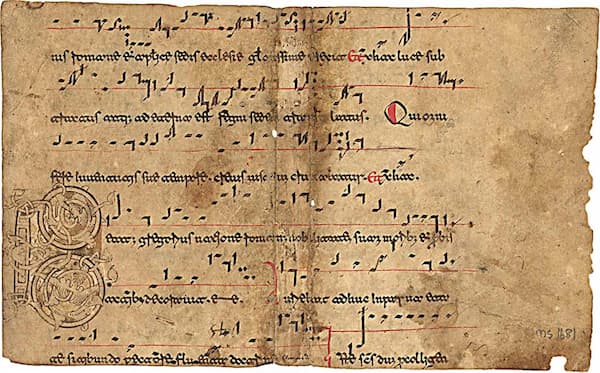

Eventually, 4-lines with an indication for a pitch became standard. In this 14th century missal from England, the lines are in red, with the first double note indicating the pitch C.

4-line notation, 14th century (National Library of Wales)

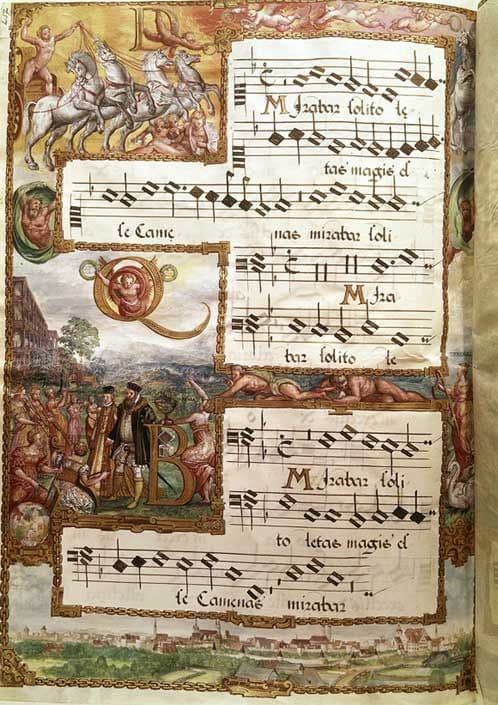

By the 15th century, 5-line notation was the standard. This permitted more extensive melodies, and they are what we still use today.

Motets of Cyprien de Rore illustrated by Hans Mielich, 1559 (Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek)

Everything we have for today’s music was developed from an idea by Guido – later, musicians and theorists may have developed them further or refined them, but it’s his basic ideas on music teaching that still help us today.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter