© Michel Catalisano on Unsplash

Athletes and experts in peak performance understand very well the concept of “tapering” – a significant reduction in training load in the days before a competition which is, paradoxically, thought to have the effect of optimising performance. This often involves lessening the amount of training hours and changing the type of training in the days leading up to a race. One of the main reasons for tapering is to minimise fatigue and thus conserve energy ready for race day. This does not necessarily mean a reduction in the intensity of training (i.e. quality of training) but rather a reduction in training volume (i.e. quantity of training). Tapering can have positive physiological and psychological benefits, aiding motivation and self-determination.

Musicians also understand the concept and benefits of tapering when approaching a performance and organise their practising and preparation accordingly.

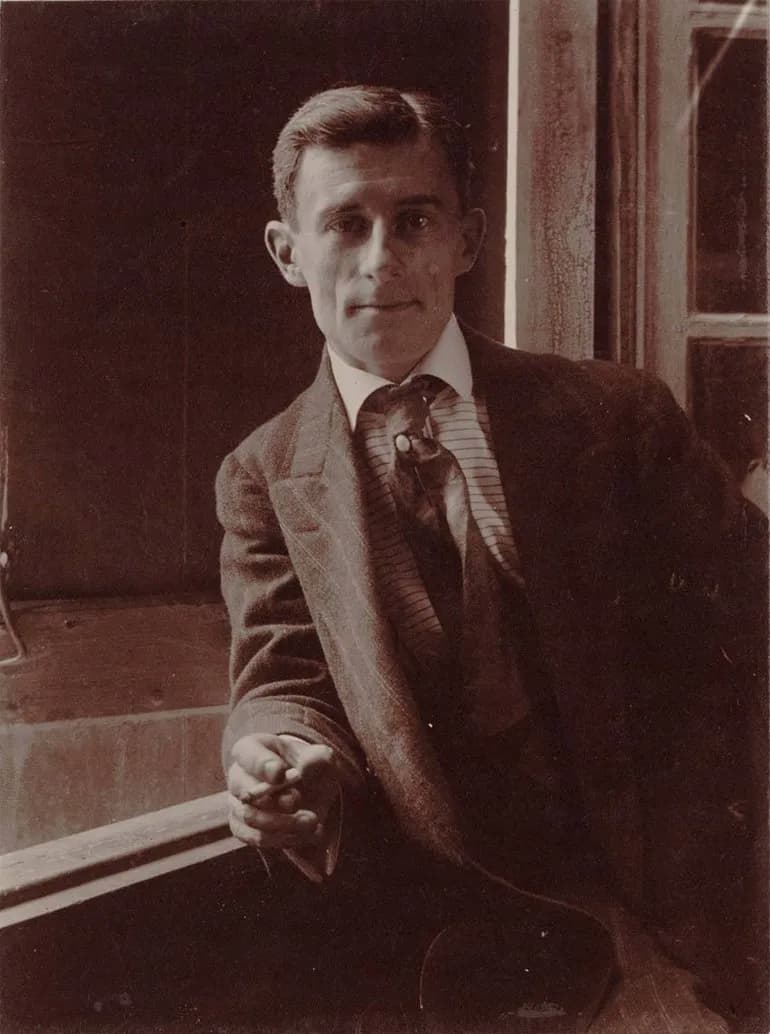

It’s not just that pieces need to be kept in the memory (muscle and mind), but the very act of playing the piano is physical and athletic. It involves reflex and endurance. It may be true that you never forget how to ride a bicycle, but if you and it are rusty there’s not much hope of winning or even completing the Tour de France.

– Stephen Hough, concert pianist

© TrainingPeaks

Practising is the musician’s regular “training” and just as top athletes organise their training for peak results, so do musicians. Practising is a finely-honed craft, crucial for the artistry of music making. Done well, it will result in a performance which is accurate and, more importantly, expressive, communicative and memorable. Hours and hours spent note-bashing in the practice room is usually counter-productive, especially in the days leading up to a concert.

Just as an athlete needs to “hold something back” for the day or the race, so the musician needs to conserve both energy and artistry for the day of the concert, and in order to bring freshness to the performance. In the law of diminishing returns, there is only so much practising that can be done when the music is thoroughly learnt, memorised and finessed and no audience wants to hear music which has been worked over to such an extent that it has lost that special ‘edge’ in performance. There also comes a point in one’s preparation where one has to accept that there is no more to be done and that one must play “in the moment” of the concert.

Bach: Cello Suite No. 1 in G Major, BWV 1007 – I. Prelude

For many musicians who employ tapering in their concert preparation, they will deliberately not play the repertoire in the concert programme in the immediate days before and on the day of the concert (it is said that Fryderyk Chopin would only play Bach prior to a performance). This is not to say that they do no practising at all, only that they change the way they practice. Some will practice the concert repertoire slowly and thoughtfully (that notion of quality rather than quantity again) or will play other repertoire.

I like to practice slowly in the morning [of a concert], on the score, looking at every detail and refreshing the memory

– Alexandra Dariescu, concert pianist

Keeping body and mind rested is also important: a surprising amount of physical and mental energy is expended when performing and conserving those reserves of energy is another aspect of tapering.

The assiduous preparation necessary to bring music to life in performance runs the risk of deadening its emotional impact; tapering ensures that the imagination and creativity of music is retained to create performances that are memorable, exciting and emotionally impactful.