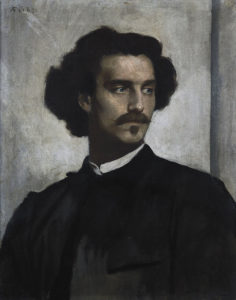

Feuerbach: Self-Portrait (1873)

The classicist painter Anselm Feuerbach was one of the artists who formed a close friendship with Brahms, and who was often compared to him. He sought in his art to both follow a stringent aesthetic and a Classical restraint, while at the same time adding in Romanticism’s more luxurious lines.

In many ways, he could be better compared with Wagner: he craved money and rich clothes, he was jealous of all others, he was vain, and a fanatical polemicist, with his favourite subject being himself. Beyond his personality, however, was a consummate artistry, bringing together intensity with a beauty of line that carry virtuosity.

In his painting Ricordo di Tivoli (Remembrance of Tivoli), painted in 1866, Feuerbach captured two Italian peasant children in the Italian area around Tivoli. Located about 30 km (19 miles) away from Rome, Tivoli was a country retreat for Rome’s ecclesiastical hierarchy, famous for its waterfalls.

Feurerbach: Ricordo di Tivoli (1866)

(Berlin: Alte Nationalgalerie)

In the picture, he uses the clothes of the children as an idealization: the girl is wearing late 19th-century peasant clothing but wears earrings and a necklace in an much older style, matching the wreath around her head. The boy, absorbed in his lute, wears ancient Roman-style clothing. She looks outward while he looks introspective, a reversal of the typical Classical styling for children. Thus they capture the eternity that is Italy.

Feuerbach is not using these classical narratives as allegories but as subjects. There’s a profound stillness around them, poised in an un-dateable landscape. Are we in the 19th century or the 9th century? The lyrical evocation brings us into the picture with them.

At the death of Feuerbach, Brahms wrote one of his last works for chorus and orchestra, Nänie (Elegie). It opens with ‘Auch das Schöne muß sterben!’(Even the beautiful must die!). The text, by Friedrich von Schiller, speaks to how beauty, which could once entice the gods, can do nothing in the face of death. Yet, the lament that is raised is far better than the silence that attends too many other deaths.

Here too, we have the restrained Classicism, and at the same time, the lyrical undertone that carries all the meaning of Brahms’ sorrow at his friend’s death. The work is dedicated to Feuerbach’s stepmother, Henriette Feuerbach, with whom the painter had been particularly close. The text makes reference to the mother of Achilles, Thetis, mourning him at the gates of Troy, and it is her lament that causes even the gods to weep.