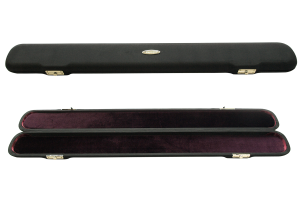

Vacations can pose dilemmas for musicians. Travelling with instruments and our children in tow has its challenges. Carrying a cello is hard enough without having to watch one’s child in crowded airports. On one of my trips to Toronto to visit family, my father entrusted me with one of the cello bows from his collection. It was a valuable 150-year-old French bow entirely crafted by hand. He put the bow in a hard-sided bow case with a little reluctance—like he wanted to kiss it good-bye … I was thrilled to have it, as the bow would enhance the quality of my cello sound.

My young son and my husband were with me, but not my cello. I couldn’t afford four airline tickets, and there really wouldn’t be time to practice. Besides, on our flight home, we were loaded with the diaper bag, a car seat, food and other carry-on items, and several new toys from grandpa. I was not accustomed to carrying a bow in a case, separate from my cello. Over and over I kept telling myself “Don’t forget the bow…Don’t forget the bow!” Placing it on the floor by the windows, along the side of the plane so that it extended under the seat in front of me, I gently set my foot on the bowcase to be sure.

Bow case

The cab driver made a speedy U-turn while I called the airport. After interminable minutes on hold they told me to go to “lost and found.” Screeching to a halt back at the terminal, I ran inside and tried to convey my dilemma to the woman at the lost baggage desk. She radioed the plane. Her news was not good. Our plane had been cleaned and was now in the air heading for Arizona. I burst into tears. Between sobs I attempted to convey to the woman the value and fragility of the item. Civilians, I told her, would assume it was a pool cue case. She assured me that once the plane was out of air space she could radio the pilot. Perhaps the cleaning crew missed the bow. Perhaps it was still on the plane.

Barber: The School for Scandal, Op. 5

French cello bow

That night I barely slept. In the morning, with apprehension, I drove to the airport. Would the bow be ok? In one piece? Scratched?

I waited impatiently for the plane to land. It seemed like hours before the passengers began to file out into the terminal. Finally, the pilot disembarked and there was my bow case looking incongruous in the pilot’s hand. He had a big grin on his face as he handed the case to me. After I checked out the bow for any signs of damage, I noted a sign, which was stuck onto the bow case. Huge red letters screamed, “Do not open. Do not jostle. Very old. Fragile. DO NOT TOUCH!!”

I hoped my gratitude was conveyed when I offered the pilot a handful of free tickets to the Minnesota Orchestra. That week we were playing an appealing all-American program including Gershwin’s An American in Paris, Copland’s Fanfare for the Common Man, and Barber’s The School for Scandal Overture. How appropriate.

Since then, the bow is called my Arizona Bow. Of course, I never told my father.