Although a relatively young institution, the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing has seen its fair share of highly talented composers. Founded in 1950, the department of composition—for better or for worse—has been the cornerstone of its academic endeavours. Guo Wenjing, originally born in the ancient city of Chongquing in Sichuan province, was one of a limited number of students admitted out of 17000 applicants when the Central Conservatory reopened in 1978. Unlike many colleagues from this acclaimed class—including Tan Dun, Chen Yi and Zhou Long—Guo remained in China after graduation. In fact, he later served as the head of the composition department at the CCOM, where he still remains on faculty today. Honored among the Top 100 Living Artists of China, Guo has composed prolifically throughout his life, and his works are performed and recorded throughout the world.

Although a relatively young institution, the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing has seen its fair share of highly talented composers. Founded in 1950, the department of composition—for better or for worse—has been the cornerstone of its academic endeavours. Guo Wenjing, originally born in the ancient city of Chongquing in Sichuan province, was one of a limited number of students admitted out of 17000 applicants when the Central Conservatory reopened in 1978. Unlike many colleagues from this acclaimed class—including Tan Dun, Chen Yi and Zhou Long—Guo remained in China after graduation. In fact, he later served as the head of the composition department at the CCOM, where he still remains on faculty today. Honored among the Top 100 Living Artists of China, Guo has composed prolifically throughout his life, and his works are performed and recorded throughout the world.

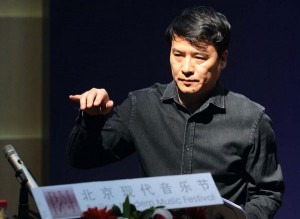

Guo Wenjing

Credit: http://www.nytimes.com/

Chen Yi

Credit: http://www.quintet.org/

Chen Yi: Suite for Cello and Chamber Winds

Tan Dun

Credit: http://www.imdb.com/

Ye Xiaogang

Credit: http://english.cri.cn/

For the opening ceremony of the 12th Macao Arts Festival in 2001, writers, producers and performing artists collaborated to produce a spectacular dance drama entitled Macao Bride. Utilizing colorful sets, lavish costume designs and virtuoso dance choreography, the production told the story of a Portuguese girl and her Macanese suitor, all set in 17th century Macao. One of the leading contemporary Chinese composers, Ye Xiaogang was commissioned to provide the musical score. A student of the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing and the Eastman School of Music, Ye’s compositions are intimately connected with the flourishing cultural scene of China. He has not only provided us with a variety of imaginative film scores, but his piano concerto Starry Sky, with Lang Lang as the soloist, was premiered during the opening ceremony of the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

Ye Xiaogang: Macao Bride