Napoléon dans son cabinet de travail (Jacques-Louis David, 1812)

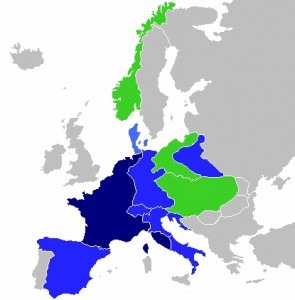

In the years before his exile, Napoleon had been opposed by six coalitions. The Third Coalition, for example, came together in April 1805, and joined the forces of Sweden, England, Russia, and Austria. The Fifth Coalition was led by Austria. It was the Seventh Coalition, made up of armies from the United Kingdom, Prussia, The Netherlands, the Kingdom of Hanover, and the Duchies of Nassau and Brunswick, bringing 118,000 men to the field, that brought Napoleon down at Waterloo in June 1815.

The victory inspired the musical world like little else: the threat of world domination (hmm sounds like today) was lifted and rejoicing was universal in the European countries, except, perhaps, France.

The most famous of the Waterloo battle compositions was Beethoven’s piece of program music, Wellingtons Sieg oder Die Schlacht bei Vittoria, Op. 91, also known as the “Battle Symphony” and “Wellington’s Victory.” The work is largely laughed at today, but it’s an important reminder of how composers can take up social phenomenon and set them to music in a way that was clearly important to them. The work is quite true to the sound-landscape of the battle, including the French and English army drum beats, the trumpet calls to action, and national music that reflects the two armies that Beethoven found important: Rule Britannia, Marlborough s’en va-t-en guerre, (otherwise in the English speaking world as For he’s a jolly good fellow), and the unmistakable rattle of gun-fire.

Beethoven: Wellingtons Sieg oder Die Schlacht bei Vittoria, Op. 91: The Battle. (Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra; Ondrej Lenard, Conductor)

First French Empire at

its greatest extent in 1811

French Empire

French satellite states

Allied states

3 Marches, Op. 45: No. 1 in C Major. (Daniela Ballek, piano, Josef Muller-Mayen, piano)

These slight works, written in 1803, are in a very popular style and reflect the wars and military preparations that were taking place across all of Europe. Vienna surrendered to Napoleon in 1797, again in 1805, and again in 1809.

When we think about works for piano four hands, we’re clearly looking at music for the home and during the various French occupations of Vienna, that’s where most of the music-making took place since public gatherings, be they rallies or concerts, were banned.

Further articles will look at other composers’ reactions to Waterloo, extending far beyond the time of the battle itself.