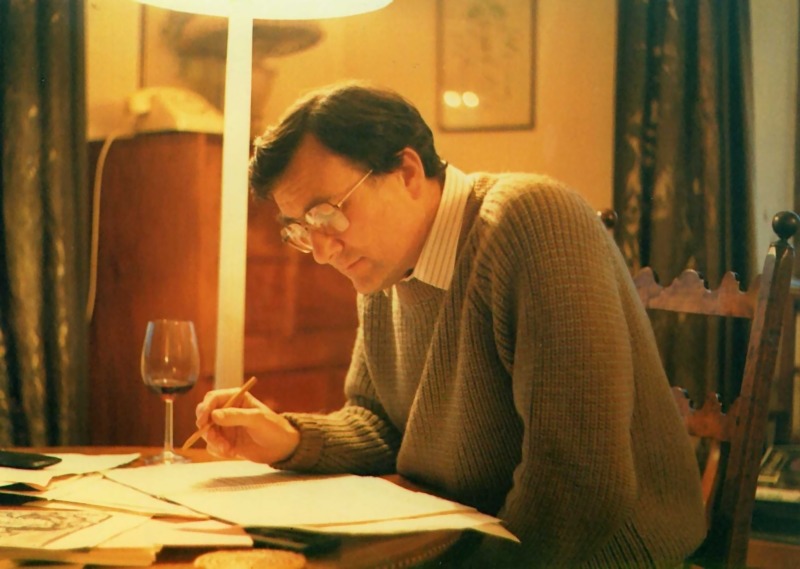

John Sanders

Credit: http://www.sanderssociety.org.uk/

Many Christian seasons have great music associated with them, and Lent is no exception. This Wednesday chapels, churches and cathedrals will ring to the sound of Gregorio Allegri’s Miserere, a setting of Psalm 51 made famous by its ringing top C for the soprano soloist and by its being restricted for performance only in the Vatican on account of its extraordinary beauty. While it is admittedly glorious, it might be that the top notes are actually a copyist’s error and that large portions of the work are actually a fourth too high! Nevertheless the sound of boy trebles (including yours truly) soaring to that high note can be one of haunting beauty. There are many other wonderful Lenten works from the Renaissance – one of my favourites is the Spanish composer Tomas Luis de Victoria’s poignant setting of the text ‘O Vos Omnes’, Jesus’ words as he hung on the cross (also set by Handel in Messiah):

O all you who walk by on the road, pay attention and see:

if there be any sorrow like my sorrow.

Behold, all people, and look at my sorrow:

if there be any sorrow like unto sorrow.

Francis Poulenc

Credit: http://www.larousse.fr/

Francis Poulenc

Quatre motet pour un temps de penitence

Francis Poulenc’s Quatre motets pour un temps de penitence come from a late period in his life when, after the death of close friend Pierre-Octave Ferroudin in a car crash, he refound his faith and wrote a series of searingly intense (and searingly difficult!) sacred choral works. The motets for Lent are among the most powerful, full of expressive and often dissonant harmonies. The third, Tenebrae factae sunt, is particularly striking as it depicts the moment of Christ’s death; at the phrase ‘et inclinato capite’ (and bowing his head), the altos sing a tortuous chromatically descending phrase before the whole choir sings, very softly, ‘emisit spiritum’ – he gave up the ghost. Many other contemporary composers have used an extended, more dissonant harmonic language in setting Lenten texts; the Scottish composer James Macmillan’s Seven Last Words from the Cross for chorus and strings has entered the repertoire as one of the most intense and powerful works of recent years. John Sanders’ The Reproaches, setting a similar text from the Good Friday service, is a favourite in the world of English church music and, in the same way that Allegri’s Miserere marks the occasion of Ash Wednesday, The Reproaches is heard in almost every church and cathedral in the country on Good Friday.

John Sanders

The Reproaches

Many parts of the Church year, and their associated texts, have inspired composers to create wonderful music, especially the seasons of Advent and Christmas itself. But to listen to some of the music for Lent written throughout the ages suggests to me that the intensity of the Passion story has been the starting point for surely some of the most powerful music ever created.

Victoria – O Vos Omnes (The Tallis Scholars / Peter Philips)

Bach – Erbame Dich (Andreas Scholl, Collegium Vocale Gent / Herreweghe)