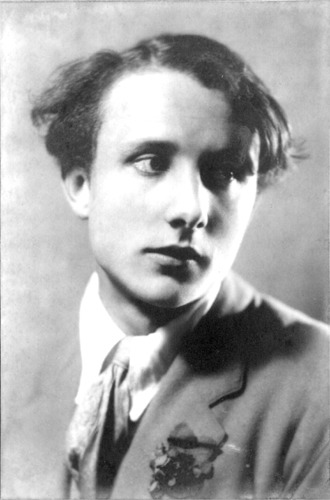

Lennox Berkeley

While Benji Britten was delighting in his fondness for the young of his own sex, he himself became the object of the desires of the poet WH Auden and the composer Lennox Berkeley. In 1935, the General Post Office Film Unit produced a series of documentary films about modern-day life, bringing together the most prominent poet in the English-speaking world and the sexually repressed and rather innocent composer. Both couldn’t get enough of “thin-as-a-board juveniles,” and quickly collaborated on the films “Coal Face” and “Night Train.” Auden, who had “never before seen such extraordinary musical sensitivity in relation to the English language,” was determined to teach young Benji the ways of the world. He encouraged him to read English poetry and keep abreast of the political situation, but above all, he made it his personal task to “bring him out.” Together with the novelist Christopher Isherwood “we tried to bring him out, if he seemed to us to need it. We were extraordinarily interfering in this respect—as bossy as a pair of self-assured young psychiatrist. Auden wasn’t a doctor’s son and I wasn’t an ex-medical student for nothing!” On one occasion Isherwood took him to a bathhouse in Jermyn Street, central London, which was “a favorite haunt for London homosexuals.” Britten wrote: “It is extraordinary to find one’s resistance to anything gradually weakening.” Auden, on the other hand cast his advice to Britten on matters of sex in the form of a poem, which Britten later set to music:

Underneath the abject willow

Lower sulk no more;

Act from thought should quickly follow:

What is thinking for?

Your unique and moping station

Proves you cold;

Stand up and fold

Your map of desolation…

…Dark and dull is your distraction:

Walk then, come,

No longer numb

Into your satisfaction.

Wystan Hugh Auden

A couple of months later, the expressed the same sentiment in slightly cruder terms:

For my friend Benjamin Britten, composer, I beg

That fortune send him soon a passionate affair.

There can be no doubt that Auden was in love with Britten, but his advances were probably rejected. Isherwood reports, “Wystan may have been in love with Ben, but there was never an affair. If there was sex between Auden and Britten, I remember nothing of it. My guess would be No. Nothing between Britten and me, either.”

Mont Juic – Suite of Catalan Dances, Op. 9 / Mont Juic, Op. 12

Variations on an Elizabethan Theme

Variation 3: Andante (Lennox Berkeley)

Variation 4: Quick and Gay (Benjamin Britten)

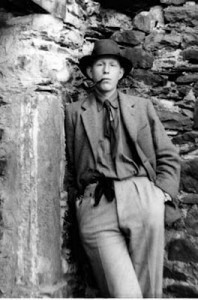

Britten and Auden

The composer Lennox Berkeley, on the other hand, met Benji in 1936 at the International Society for Contemporary Music Festival in Barcelona. Lennox had studied with Nadia Boulanger in Paris, and was acquainted with Poulenc, Stravinsky, Milhaud, Honegger and Roussel. Lennox had had a number of homosexual affairs, including a current one with José Raffalli, and Benji was certainly on the menu. They very much enjoyed nude sunbathing and together with the young critic Peter Burra, visited the red-light district of the Catalonian capital. The watched cross-dressing revues and sexually explicit performances, and Britten was revolted. “I was shocked by the sordidity” he wrote, “sexual temptations of every kind at each corner.” Berkeley was “besotted” with Britten, but in the end, did not get his way with Benji. “He is a dear & I am very, very fond of him,” wrote Britten, “nevertheless, it is a comfort that we can arrange sexual matters at least to my satisfaction.” Despite, or because of it, Lennox and Benji remained close friends and collaborated on a number of works, including a suite of Catalan dances entitled Mont Juic, and Variations on an Elizabethan Theme. In our next episode, Benji visits the Folies Bergère in Paris to investigate heterosexual practices, and eventually falls in love with the singer Peter Pears.

Here is my response to this article and the way it’s been circulating: https://notanothermusichistorycliche.blogspot.com/2016/11/did-wh-auden-uncloset-benjamin-britten.html?m=1