Paul Hindemith: Die Serenaden, Op. 35 “Duett for Viola and Violoncello”

Paul Hindemith: Die Serenaden, Op. 35 “Duett for Viola and Violoncello”

At the beginning of 1940, Gertrude was still stuck in Switzerland and desperately looking for a way to join her husband, who had secured lectureships at the University of Buffalo, Cornell University, Wells College and Yale University. As Europe was plunged into the maddening absurdity of WW2, traveling became increasingly difficult, if not impossible. Bureaucratic measures around the world were specifically designed to deter unwanted immigrants. Gertrud had a confirmed passage, leaving Genoa for New York. However, Italy declared war on France and Britain on 10 June 1940, which US President Roosevelt described as “a dagger struck into the back of its neighbor.” As a result, all passenger travel between Italy and the US ceased with immediate effect.

This created a rather serious problem for Gertrude. If she left Switzerland to find alternative travel, but failed to do so, she would not be allowed to return. Furthermore, her American visa was only valid for four months, and an extension only granted on the condition of a paid and confirmed ship passage. Yet, a ship passage could only be obtained with a valid visa. Gertrude, however, was not prone to paralysis. In consultation with Paul, she deposited his musical manuscripts with friends, and began an arduous journey through Grenoble, Montpellier, Perpignan, Barcelona and Madrid, before eventually arriving in Lisbon on 25 of August. Paul always traveled with her in spirit, “with fingers crossed until they were blue in the hopes that nothing bad would happen and everything would work out fine.” Paul and Gertrud were finally reunited in on 12 September 1940. Once they arrived in New Haven, Gertrude began her studies in Romance languages and literature, Paul founded the Collegium Musicum — with Gertrud singing in the choir — and both obtained American citizenship in January 1946.

This created a rather serious problem for Gertrude. If she left Switzerland to find alternative travel, but failed to do so, she would not be allowed to return. Furthermore, her American visa was only valid for four months, and an extension only granted on the condition of a paid and confirmed ship passage. Yet, a ship passage could only be obtained with a valid visa. Gertrude, however, was not prone to paralysis. In consultation with Paul, she deposited his musical manuscripts with friends, and began an arduous journey through Grenoble, Montpellier, Perpignan, Barcelona and Madrid, before eventually arriving in Lisbon on 25 of August. Paul always traveled with her in spirit, “with fingers crossed until they were blue in the hopes that nothing bad would happen and everything would work out fine.” Paul and Gertrud were finally reunited in on 12 September 1940. Once they arrived in New Haven, Gertrude began her studies in Romance languages and literature, Paul founded the Collegium Musicum — with Gertrud singing in the choir — and both obtained American citizenship in January 1946.

Immediately after the war, Hindemith was urged to return to Germany to rebuild the cultural and musical life, a request he dismissed decisively. However, the couple soon traveled to Europe to visit family and friends, and Paul gave concerts and lectures throughout the continent. In 1949, he received an offer from the University of Zurich and for the next five years commuted between Zurich and New Haven. On 2 May 1953, the Hindemith’s bid farewell to the United States and moved to Switzerland. They settled in the Villa La Chance in Blonay, a small town overlooking Lake Geneve. It became their private retreat in the midst of Paul’s frantic teaching, publishing and conducting obligations. On 16 November 1963, following a high fever, Paul was admitted to a Frankfurt hospital for further examination. Once there, he suffered a series of strokes and passed away on 28 December. Almost immediately — as a personal therapeutic activity — Gertrud began to organize Paul’s heritage, “our entire legacy is to be transformed into a Hindemith Foundation, the principal activities of which should be to look after the musical and literary estate of Hindemith and to continue expanding the archive in our house in Blonay that I have begun to set up.”

Immediately after the war, Hindemith was urged to return to Germany to rebuild the cultural and musical life, a request he dismissed decisively. However, the couple soon traveled to Europe to visit family and friends, and Paul gave concerts and lectures throughout the continent. In 1949, he received an offer from the University of Zurich and for the next five years commuted between Zurich and New Haven. On 2 May 1953, the Hindemith’s bid farewell to the United States and moved to Switzerland. They settled in the Villa La Chance in Blonay, a small town overlooking Lake Geneve. It became their private retreat in the midst of Paul’s frantic teaching, publishing and conducting obligations. On 16 November 1963, following a high fever, Paul was admitted to a Frankfurt hospital for further examination. Once there, he suffered a series of strokes and passed away on 28 December. Almost immediately — as a personal therapeutic activity — Gertrud began to organize Paul’s heritage, “our entire legacy is to be transformed into a Hindemith Foundation, the principal activities of which should be to look after the musical and literary estate of Hindemith and to continue expanding the archive in our house in Blonay that I have begun to set up.”

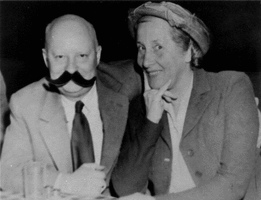

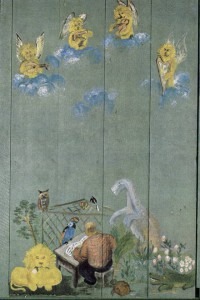

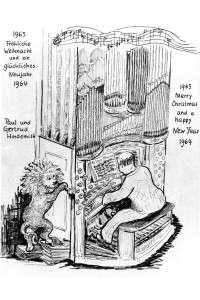

Gertrude died on 13 March 1967, and she is buried next to Paul in St. Légier. By now you surely have noticed that the Hindemith’s were a painfully private couple, their public life and private identities diametrically opposed. Do we really know how they felt about each other? Of course we do, and ample evidence is found in Paul Hindemith’s drawings. Hundreds of pictures and small-scale drawings not only give evidence of Paul’s remarkable talent as a draftsman, but also of his love and devotion to his wife. You see, in the Zodiac, Gertrud was born under the sign of Leo, the Lion. And in Paul’s drawings, the lion is everywhere! It decorates benches, lamps, walls, letters, Christmas cards, calendars, napkins, tablecloths, envelopes and even musical manuscripts. In addition, the couple also appears in music. Die Serenaden Op. 35 are dedicated to Gertrud, and the viola and cello — their favorite instruments emblematically representing the couple — are intimately intertwined and united. Paul could simply not have existed without Gertrud, and she felt the same way. But that’s clearly none of your business!

Gertrude died on 13 March 1967, and she is buried next to Paul in St. Légier. By now you surely have noticed that the Hindemith’s were a painfully private couple, their public life and private identities diametrically opposed. Do we really know how they felt about each other? Of course we do, and ample evidence is found in Paul Hindemith’s drawings. Hundreds of pictures and small-scale drawings not only give evidence of Paul’s remarkable talent as a draftsman, but also of his love and devotion to his wife. You see, in the Zodiac, Gertrud was born under the sign of Leo, the Lion. And in Paul’s drawings, the lion is everywhere! It decorates benches, lamps, walls, letters, Christmas cards, calendars, napkins, tablecloths, envelopes and even musical manuscripts. In addition, the couple also appears in music. Die Serenaden Op. 35 are dedicated to Gertrud, and the viola and cello — their favorite instruments emblematically representing the couple — are intimately intertwined and united. Paul could simply not have existed without Gertrud, and she felt the same way. But that’s clearly none of your business!

More Love

- Untangling Hearts

Klaus Mäkelä and Yuja Wang What happens when two brilliant musicians fall in love - and then fall apart? -

The Top Ten Loves of Franz Liszt’s Life Marie d'Agoult, Lola Montez, Marie Duplessis and more

The Top Ten Loves of Franz Liszt’s Life Marie d'Agoult, Lola Montez, Marie Duplessis and more - Mathilde Schoenberg and Richard Gerstl

Muse and Femme Fatale Did the love affair between Richard Gerstl and Mathilde Schoenberg served as a catalyst for Schoenberg's atonality? - Louis Spohr and Marianne Pfeiffer

Magic for Violin and Piano How did pianist Marianne Pfeiffer inspire a series of chamber music?