Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina: Missa papae Marcelli, “Gloria”

Published in 1567, the Missa Papae Marcelli (Pope Marcellus Mass) — one of roughly 104 complete mass settings composed by Palestrina — sounds smoothly crafted and flowing melodies that dynamically combine to produce full consonant harmonies. Stepwise melodic motion in individual voice parts created arch-like contours, and carefully controlled counterpoint resulted in full triadic chords on each beat. Most importantly, however, is Palestrina’s skillful alternation of homorhythmic and polyphonic textures. A giving voice group simultaneously pronounces a segment of text in speech rhythm, thereby assuring that the text can be clearly understood. Palestrina’s style of composition was the first in the history of Western music to be consciously preserved and imitated as a model in later ages. It proved particularly influential on a number of Spanish composers studying and working in Rome.

Tomás Luis de Victoria: O vos omnes (Oh, all of you)

Tomás Luis de Victoria: O vos omnes (Oh, all of you) Victoria (1548-1611) spent over twenty years of his life in Rome and thoroughly absorbed the Palestrina style. The overall form of his motet setting O vos omnes, composed for the Office during Holy Week, was determined by the textual and musical form of the original plainchant settings. The music, a devout, pious and intensely fervent setting of the text strives for complete triadic harmony. Victoria returned to Catholic Spain in 1587 and assured that the “Roman” style of music found an enthusiastic following on the Iberian Peninsula. Under the influence of the Counter-Reformation, the “Roman” style also made its way across the Alps. Orlando di Lasso (1532-1594) stationed in Munich and employed by Albrecht V, the Duke of Bavaria, had already published several books of madrigals and chansons by the age of twenty-four. In all, he would compose more than two thousand works during his lifetime.

Orlando di Lasso: Lamentations of the Prophet Jeremiah

Lasso devoted much of his later years to setting sacred texts, particularly spiritual madrigals. He “renounced the merry and festive songs of my youth for music of more substance and energy.” A highly versatile composer, Lasso “synthesized the musical achievements — Franco-Flemish counterpoint, Italian harmony, Venetian opulence, French vivacity and German severity — of an entire era.” The musical influence of the Counter-Reformation also touched the British Isles, and William Byrd (1543-1623) was the first English and Catholic composer who thoroughly grasped the imitative techniques of Palestrina. In 1607, he described the generative power of the scripture. “I have found there is such a power hidden away and stored up in the words of the Scripture, that one who meditates on divine things, pondering them with detailed concentration, all the most fitting melodies come as it were of themselves, and freely present themselves when the mind is alert and eager.”

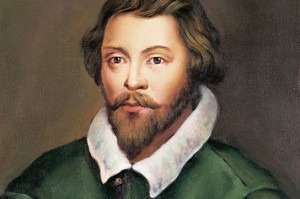

William Byrd

A devout Catholic, Byrd was liable to imprisonment for attending Mass and could be fined for non-attendance at services of the Church of England. Despite this oppressive environment, Byrd quickly rose to become one of the finest musicians of his day and was subsequently eulogized as “Britain’s greatest composer.” The principle aims of the Counter-Reformation met with limited success — unless, of course one considers millions of new souls recruited by Jesuits in the Americas and the Far East — but it certainly has left us an unmistakable corpus of breathtakingly magnificent music.