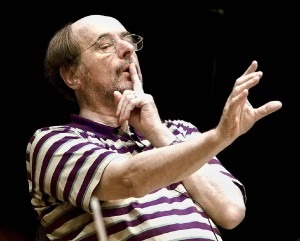

Sir Roger Norrington

‘Is this the greatest piece ever written?’ Such was the question fired at me by Sir Roger Norrington during our correspondence in preparation for the recent performance of Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis, given by the combined choirs and orchestras of Cambridge University in King’s College Chapel, conducted by Sir Roger himself. Norrington is an alumnus of Clare College, and perhaps the key figure in the development of historically informed musical performances during the 1970s – with extraordinary energy, imagination and a large dose of historical proof, he set about reimagining all sorts of music from Schütz to Wagner (and in recent years, even to Mahler) with the aim of playing that music, as far as possible, as it was played when it was written. That means – more often than not – smaller orchestras, fast tempi and, most notoriously, ‘pure tone’, or no vibrato, giving the sound an exciting edge and vitality in fast music, and a wonderful depth and profundity in slower music.

There’s plenty of both in the Missa Solemnis, and I spent a wonderful week assisting Sir Roger as he brought this music to life with Cambridge students. Assisting a conductor is an interesting task in itself – after leading the orchestra through an initial playthrough before Sir Roger joined us, I spent time in King’s evaluating balance issues between choir and orchestra, checking that the choir’s text was audible (never easy in a resonant acoustic like King’s) and occasionally suggesting where perhaps something might work better if played slightly differently. I have to confess, though, that the best part was getting to spend a week listening to the Missa Solemnis every night. I had spent a lot of the Christmas vacation learning the piece in order to prepare for my rehearsal with the orchestra, so I thought I knew it quite well – but I had barely scratched the surface, and (like so many works) the impact of a recording is trifling compared to that of a live performance, especially of this monumental work.

King’s College Chapel

There are obvious reasons for this – it hasn’t got a tune to rival the Ode to Joy, and it’s ferociously difficult to perform. But there is also a more subtle reason, which I believe lies in a fundamental difference in the messages of the two works. The Ninth moves from a state of disorder and darkness at its opening to a glorious celebration of human brotherhood and hope, from chaos to certainty. The Missa Solemnis takes the opposite journey, from the stability of the unison cries of ‘Kyrie’ at the beginning to an oddly abrupt, almost unresolved ending. The words that close the Mass, ‘dona nobis pacem’ (grant us peace) seem outwardly conciliatory, full of relaxed certainty in a peaceful future. Indeed, they are most often set like that, a major resolution of usually stormy, minor-key cries of ‘miserere nobis’ (have mercy upon us). Beethoven follows that harmonic path, but undercuts that with two sudden interjections of military trumpets and drums, the army banging at the gate. Sir Roger was keen to impress on us during rehearsals that Beethoven lived in Vienna during wartime – he knew the sound of warfare, and the frailty of peace. So the Agnus Dei presents an ambiguous ending – we seem to reach some kind of resolution with the last few orchestral chords, but the sound of warfare is still ringing in our ears. We have moved from a communal call in prayer to profound uncertainty about the future – the exact opposite of the Ninth.

So the Ninth is powerfully affirmatory, and looks to the future, whereas the Missa Solemnis is in the final reckoning ambivalent, unsettling and spends a lot of time looking to the past. It’s a no-brainer – but if you give yourself one musical project this year, make it to get to know the Missa Solemnis. It’s utterly extraordinary, and a list of my favourite passages could take up another two articles. There’s one, though, that’s too good not to share. After the energy of the opening section of the Credo, we suddenly hit a wall – the music halves in speed, and we reach D minor for the words ‘Et incarnatus est’. The tenors of the choir intone the words in which Jesus was made man and dwelt among us to the accompaniment of violas and cellos; the same music is taken up by a few string players and the four soloists, while the flute, the Holy Spirit appearing as a dove, flutters serenely over the top of the texture. It’s an amazing moment, like so many in this work. But enough of me telling you about it – go and have a listen, live with it for a few weeks like I did, and become one of the few people who actually know Beethoven’s greatest achievement.

A well written piece, Will. This performance – which I attended – brought the wheel full circle for me. The greatest concert I have been to was a performance of the Missa Solemnis under Otto Klemperer in 1965. (Sir) Roger was in the choir that night. I suspect many serious music lovers know the Mass for what it is, but for me, like a great wine (to descend to the trivial) it has to be a rare experience, so exalted is it.

For that matter, his ‘other’ (sic!) Mass, , The Mass in C, although quite Beethovian in every which way, has not been projected well enough by the Concert community…or for that matter, the media.. It has all the stuff a great Mass should have, but yet…,

Perhaps Beethoven tried a ‘little too hard’ with his religious music….

Whenever l hear this mass, glorious as it truly is, l cannot help but recall this film:

https://www.theguardian.com/film/filmblog/2014/jul/29/malcolm-mcdowell-mick-travis-if-role-model