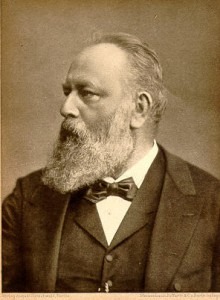

Theodore Billroth

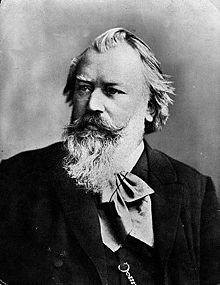

Brahms

String Quartet in C minor, Op. 51, No. 1

“It is one of the superficialities of our time to see in science and in art two opposites. Imagination is the mother of both.” These thoughtful words, uttered towards the end of the 19th century, stem from the pen of the father of modern abdominal surgery, Christian Albert Theodor Billroth. Appointed professor of surgery at the University of Vienna and chief of surgery at the Vienna General Hospital in 1867, Billroth was directly responsible for a number of surgical landmarks. He performed the first esophagectomy in 1871, the first laryngesctomy in 1873, and perhaps most famously, the first successful gastrectomy in 1881. Even today, a number of diseases and surgical procedures are named after him.

Johannes Brahms

However, Billroth not only had a steady hand and strong stomach, he also had a burning love for music. He was a talented amateur pianist and violinist, and during his stay in Switzerland he served as the music critic for the Neue Züricher Zeitung for seven years. He also guest conducted the Zürich Symphony Orchestra and tried his hands at composition. Yet in the musical world, he his primarily remembered for his friendship with Johannes Brahms. Billroth came to Vienna in 1867 on appointment from the Austrian Emperor Rudolf and he quickly thanked him by designing a maternity hospital, the “Rudolfinum,” which today serves as a student dormitory. Brahms arrived in 1869 after having been rejected for a conducting post in his hometown of Hamburg, and he decided to make Vienna his home. Brahms had never gone to University — a fact he preferred to keep a closely guarded secret — and as a result always surrounded himself with highly educated people. His friendship with Billroth, however, was genuine enough and lasted for decades. Much of Brahms’s chamber music for strings was first performed in Billroth’s home, with the surgeon participating as a musician in trial rehearsals. Brahms would frequently send Billroth his original manuscripts for evaluation prior to publication.

Parkhotel Billroth

Of course, Brahms being Brahms, he happily kept ignoring all of Billroth’s suggestions. Nevertheless, Brahms did dedicate the two string quartets Op. 51 to his surgeon friend who wrote, “I am afraid these dedications will keep our names longer in memory than the best work we have done. For us not very complimentary, but beautiful for humanity, which with the right instinct considers art more immortal than science.” For twelve years, Brahms spent his summer holidays in the resort and spa village of Bad Ischl, which also served as the summer residence of Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria. Billroth was never far behind, and while Brahms was composing his latest masterpiece, Billroth busily designed and build five stately houses in the nearby town of St. Gilgen. You can still visit and stay at one of his creations, the “Parkhotel Billroth” today. On occasion, the two friends also shared a bit of laughter. Mathilde Wesendonck — once romantically entangled with Richard Wagner — sent a poetic text to Brahms in 1874 in the hope that he would set it to music. The ode in question dealt with cremation, a highly controversial subject at the time, and Brahms was asked to compose a Cantata for chorus and soloists. Brahms derived much amusement from her request, as did Billroth and a whole host of other friends who were privy to the “Cremation Cantata Project.” Towards the end of his life, Billroth attempted to apply scientific method to the subject of music, and drafted an essay entitled “Wer ist musikalisch?” (Who is musical?). This scientific investigation of musicality — which was completed and published by the highly influential music critic Eduard Hanslick after Billroth’s death — also received some pointers from Johannes Brahms.

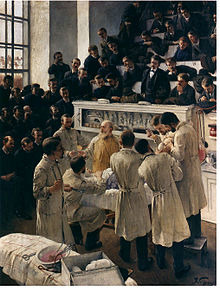

Billroth operating

Billroth specifically wanted to know what makes a melody beautiful. “This morning I spent two highly interesting hours with Brahms. He spoke to me with great animation about the formation of melodies, and demonstrated the musical beauty of the Bach Sarabandes. In these moments he can be so warm and amiable that one regrets that he is not always so. When I asked him about the indicators of beauty in a melody, he countered with a poem by Goethe and provided the most interesting analysis. It all confirmed the opinion that I had already developed. As to the final cause of whether something is poetically or musically beautiful, one can make no assertion, because it is a case of individual perception.” Brahms, however, clearly knew that beauty is not “in the eye of the beholder,” and that musical technique and specific artistic beauty are inseparably bound. Beauty, as we all know, is always apprehended by the mind, that is, it resides in an idea and not with a “feeling.” Surely that is the reason why Brahms steered Billroth towards poetry in the first place! Maybe it’s time to follow Brahms’s suggestion and read a bit more poetry?