With the nationalist revival in the 19th century, the different regions of Spain saw a diverse musical development, from the Basque-language choirs in the north, to the melting pot in Castile, León and Aragon, where Roman, Visigoths, French, Italian and Gypsy influences are felt, to Catalonia, where the ‘sardana’ originated – and to Andalusia’s ‘flamenco’, which is considered the quintessential musical expression of Spain, famous all over the world, its roots reaching back to Phoenicians, Visigoths, Moors and Jews.

Many artists and writers were entranced by the lament of the ‘soléa’, the guitar accompaniment of the ‘seguiriya’, and the sinuous and voluptuous movements of the Flamenco dancers. The music itself was handed down from one generation to another, often through the gypsy dynasties of Andalusia, defying academic structures, never executed twice the same way – an individual art par excellence.

Guitarists mark the rhythm of the performance. The singers, standing, back up the dancers, punctuating the rhythm with their hands clapping and heels clicking; up front, usually only one male or female dancer performs for the audience. Here too, the pure essence of flamenco is individuality.

In 1922, in Granada, García Lorca, Manuel de Falla and Andrés Segovia tried to revive the true form of flamenco, the ‘cante jondo’ (deep song) with a Festival of Flamenco. García Lorca was particularly concerned in bringing back the ‘duende’ (evil spirit, demon or poltergeist). The meaning of ‘duende’ in the artistic sense is close to the Greek concept of ‘daimon’, signifying a god or divinity, but here, it represents more the genius of a person, and in particularly that of an artist. As Lorca said himself “The appearance of the duende always presupposes a radical change of all forms based on old structures. It gives a sensation of freshness wholly unknown, having the quality of a newly created rose, of miracle, and produces in the end an almost religious enthusiasm” (The Theory and Function of the Duende – lecture given by Lorca in 1933).

Again, the connection to the visual arts, and in Garcia Lorca’s case, to literature, which we will explore in our upcoming July article, imposes itself at this point.

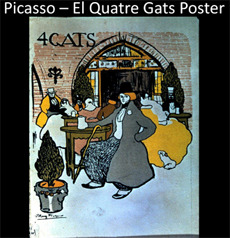

The early work of Picasso in Barcelona which is closely connected to the Arts and Crafts movement, not only in that city, but in the rest of Europe as well, is a poster in the style of Toulouse-Lautrec. The flattened perspective and figures and the limited use of color break with traditional perspective and concepts in the arts and raise the advertisement, the poster, to the same level of artistic value as paintings.

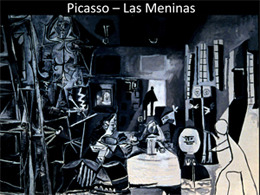

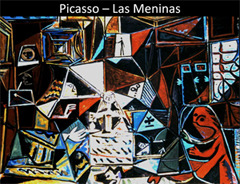

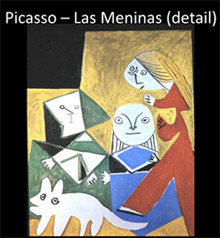

Space is no longer the traditional space of Renaissance paintings, but becomes distorted, re-invented and outright imaginary. In Dalí’s work, the Velázquez’ painting Las Meninas, is projected into a cloud-scape, a dream-scape, alluding to the Freudian concept of the sub-conscious; Dalí includes himself (i.e. his shadow) in the painting, the brush and its shadow are reflected on the canvas as well, simultaneously implying Dalí’s absence and his presence as the creator of the painting.

In architecture, the buildings of Gaudí reiterate similar concepts. Highly individual, his buildings, such as the Casa Battló, make reference to nature — in this case, the exterior with its bluish/greenish tiles — to the sea, harking back to the Moorish tradition of the Middle Ages. Its roof and the details of the windows replicate a giant sea monster.

All of Gaudí’s buildings are topped with off-centered crosses, which take us back to García Lorca’s concept of ‘duende’, radical change of all forms based on old structures which results in “religious enthusiasm”. Gaudí’s last work, the unfinished Church of the Sagrada Familia in Barcelona, also has to be seen in this light. The only façade of the church finished during Gaudí’s lifetime uses Moorish architectural elements which resemble the beehive construction of the interior courtyards of the Alhambra in Granada.

According to Dalí, when his friend García Lorca saw the façade of Sagrada Familia for the first time, he “claimed to hear the ‘griterio’ – a cacophony of shouts (reminiscent of the ‘soléa’) – that rose stridently to the top of the cathedral, creating such tension in him that it became unbearable. There is the proof of Gaudí’s genius, he appeals to all our senses and created the imagination of the senses” (quoted from Dalí’s autobiography).

Music, the arts and literature exhibit the same dynamics, which we will explore further in our July article with the works of García Lorca, Manuel de Falla and others.

Camarón de la Isla sings Romance de la luna based on a poem by García Lorca.

Carmen Amaya (1939)

Rare Flamenco Guitar Video: Carlos Montoya – Farruca