Hungarian composer Béla Bartók (1881–1945) wrote two ballets, one that has achieved some fame (The Miraculous Mandarin of 1926), but the other has faded from today’s stages. In its time, however, the first ballet, The Wooden Prince, was staged everywhere.

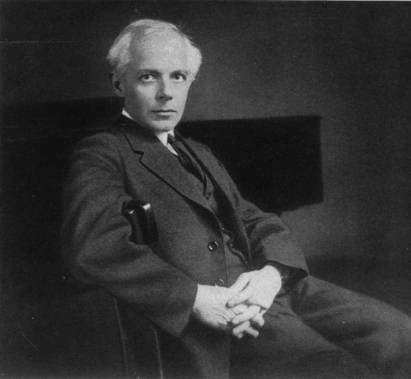

Béla Bartók, 1927

The Wooden Prince, in Hungarian A fából faragott királyfi, Op. 13, was composed between 1914 and 1916 and staged in 1917 at the Budapest Opera. It was a success at its premiere and prompted the Budapest Opera to stage the premiere of Bartók’s opera Bluebeard’s Castle, which had been postponed since 1911.

The orchestra for the ballet is larger than usual, including 4 woodwinds (4 flutes, 4 oboes, etc.) where normally 2 or 3 would be called for: alto, tenor and baritone saxophones, extra brass, extra percussion, 2 harps and extra strings.

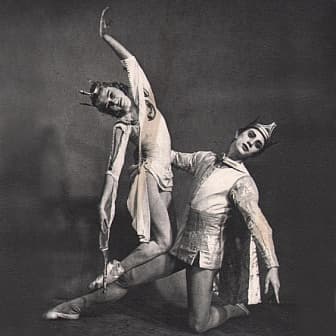

The Wooden Prince, 1966 (Mikhailovsky Theatre)

In the story, the Prince falls in love with a Princess, but a Fairy intervenes, separating the lovers with a wide river. The Prince catches the eye of the Princess by hanging his cloak in a tree, adding hair and a crown for verisimilitude. The Princess comes and dances with the Wooden Prince, which the Fairy has brought to life. The Prince is despondent – she’s going off with the wrong prince! The Princess quickly finds, however, that her Wooden Prince is not very responsive to her desires. The Prince falls asleep, and the Fairy exchanges the live Prince with the Wooden Prince and all is well again.

The writer of the story, Béla Balázs (1884–1949), who wrote the libretto for Bluebeard’s Castle, found Bartók in a depression and encouraged him to write the music for the ballet. When Bartók started to work, it was his first composition in many months. In a way, The Wooden Prince is a twist on the Pygmalion story – instead of the artist falling in love with his statue, here the creator’s love falls in love with his creation. In both scenarios, divine intervention (gods or fairies) is involved. Some writers see this as the intervention of the forces of Nature, while others see it as the difficulties of the path of true love. Is the Princess so self-absorbed that she can’t see the non-human core of the Wooden Prince? True value and inner beauty are other questions that are driven by a deeper reading of the story.

The ballet was made into a short orchestral suite in 1925, consisting of three dances, and a longer orchestral suite in 1932.

The enchanted forest is summoned in a sonorous and delicate C major.

Béla Bartók: A fából faragott királyfi szvit (The Wooden Prince Suite), Op. 13, BB 74 – I. Prelude (Philharmonia Orchestra; Neeme Järvi, cond.)

The Princess appears and dances, and the Prince sees her and falls in love.

Béla Bartók: A fából faragott királyfi szvit (The Wooden Prince Suite), Op. 13, BB 74 – II. Dance of the Princess in the Forest (Philharmonia Orchestra; Neeme Järvi, cond.)

The Fairy attempts to persuade the prince that her forest realm is better than the outside world. She first brings the forest to life in The Trees Dance for the Fairy, and here Bartók’s skill in orchestration, particularly with such a large orchestra, comes to the fore.

Czár Gergely as The Prince in Bartók’ The Wooden Prince, 2016 (Szeged Contemporary Ballet and the National Dance Theatre)

Béla Bartók: A fából faragott királyfi szvit (The Wooden Prince Suite), Op. 13, BB 74 – III. Dance of the Trees (Philharmonia Orchestra; Neeme Järvi, cond.)

Next comes a dance of the waves as the Fairy sets even the waters of the river into animation. All of this is the Fairy’s attempt at wooing the Prince into her world. The Princess, having finished her dance, is sitting in her castle, spinning. The wave music is where the three saxophones perform, bringing an early jazz-influenced idea to the music but above a very romantic-influenced swirl of water in the strings.

Béla Bartók: A fából faragott királyfi szvit (The Wooden Prince Suite), Op. 13, BB 74 – IV. Dance of the Waves (Philharmonia Orchestra; Neeme Järvi, cond.)

When the Princess comes to dance with the animated Wooden Prince, the music tells us immediately of the problems she’s encountering with this non-man. The tempo speeds up and stamps back into a slow tempo. Abrupt shifts of rhythm can only be frustrating to the live Princess. Inevitably, the Wooden Prince is but a simulacrum and fails. Some of the stylistic elements in this dance come from Bartók’s and his friend Zoltán Kodály’s work on folk music, particularly the verbunkos style that we are more familiar with in his later music.

Béla Bartók at home with his carved and painted peasant furniture, 1908

Béla Bartók: A fából faragott királyfi szvit (The Wooden Prince Suite), Op. 13, BB 74 – V. Dance of the Princess with the Wooden Doll (Philharmonia Orchestra; Neeme Järvi, cond.)

The Princess sees the Prince. He tries to console her for her loss of the Wooden Prince and, in looking at him for the first time, she sees a new reality. As much as the Fairy has tried to bring the Prince to her world of Nature, it’s the outside world and love that capture his and the Princess’s hearts.

The Wooden Prince, 2018 (National Dance Theatre, Hungary) (Photo by Rajnai Richárd)

Béla Bartók: A fából faragott királyfi szvit (The Wooden Prince Suite), Op. 13, BB 74 – VI. The Prince comes up and tries to console her (Philharmonia Orchestra; Neeme Järvi, cond.)

In the end, we return to the quiet C major of the beginning. We start with Nature, alone its glory, before all these humans started emoting all over the landscape. The forest slowly delivers us back to the real world as it loses its enchantment, and the quiet C major returns us to reality.

Béla Bartók: A fából faragott királyfi szvit (The Wooden Prince Suite), Op. 13, BB 74 – VII. Postlude (Philharmonia Orchestra; Neeme Järvi, cond.)

Bartók’s work on The Wooden Prince has been compared with many other influential works. The opening of the ballet, on its beautiful C major, has been seen as similar to the opening of Das Rheingold by Wagner – a ‘near pulseless, triadic sound that slowly pushes higher into the orchestral registers, gaining power and motion as it grows’. Some of the dances show the influence of Stravinsky in their use of pulsing rhythm.

One important orchestral climax that is missing from the two different suites created from the full ballet score is called ‘The Great Apotheosis’. After the Fairy has shown the Prince the glories of nature with its dancing trees and waves, and he’s seen the initial failure of the Wooden Prince as a dancing partner, he’s in despair. In the score, the Fairy takes the prince’s hand and leads him to the hill. Triumph, radiancy and splendour. “Here you will be King over everything!” She wants to show him the folly of pursuing love when all nature is open to him in his loneliness. However, the great climax is on C sharp minor, not the comforting C major of the beginning. Is it really as ideal as the Fairy is indicating? Is he destined for a life of loneliness? Fortunately, the Princess returns, and we have a more normal ending, but for an instant, the Fairy holds sway.

Béla Bartók: A fabol faragott kiralyfi (The Wooden Prince), BB 74 – Great Apotheosis –(Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra; Marin Alsop, cond.)

This climax is pure Bartók, with no outside influences. This is the chromatic, passionate Bartók we will get to know better in his later works.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter