Michael Daugherty: Fire and Blood

In 1933, a set of 27 fresco panels by the Mexican artist Diego Rivera was unveiled at the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA). Rivera (1886–1957) brought the idea of murals to life. His enormous works, which covered entire walls and were often on in large multi-panel sets, such as his 1940 mural The Marriage of the Artistic Expression of the North and of the South on This Continent, commonly known as Pan American Unity, which measures 22 by 74 feet (6.7 m x 22 m) and weighing over 60,000 pounds (27,200 kilos).

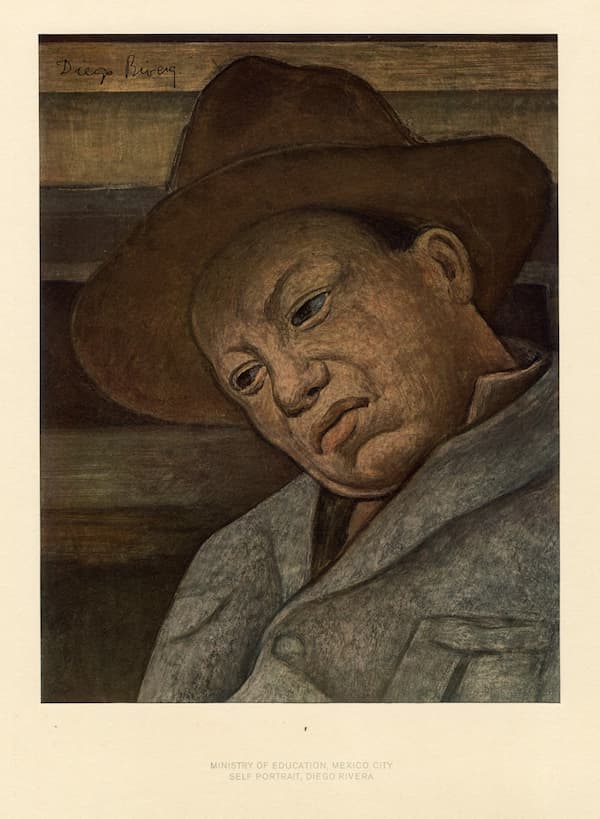

Diego Rivera: Self-Portrait from the Portfolio “Frescoes of Diego Rivera”, 1933

Between 1923 and 1924, Rivera covered the 3-storey courtyard at the Ministry of Public Education Building in Mexico City with 124 frescos.

Rivera’s art was always political and caused problems: his art for Rockefeller Center in New York, commissioned by John D. Rockefeller, was plastered over before it was complete and destroyed because of its portrait of Lenin and its Marxist pro-worker content. The fresco was removed from the wall in 1923, and only black-and-white photos remain of the original (made by Rivera, who suspected what Rockefeller might have done). Rivera recreated just the central section (Man at the Crossroads) in a smaller format in 1934; it’s now at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City. The flanking panels, The Frontier of Ethical Evolution and The Frontier of Material Development, which depicted socialism and capitalism, were never created.

Diego Rivera while working on the north wall of his Detroit Industry Murals at the DIA, 1933 (Detroit Institute of Arts)

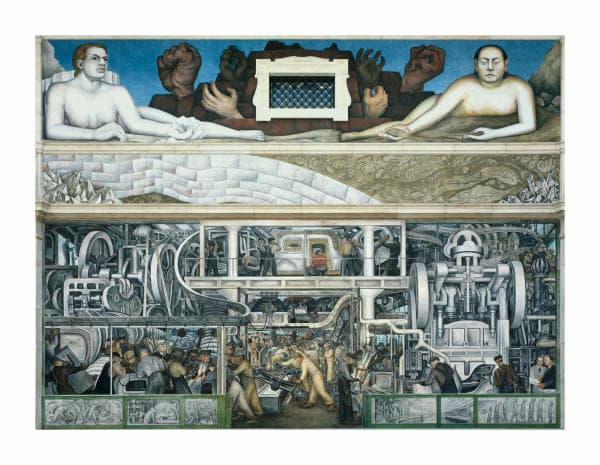

In Detroit, the murals, entitled the Detroit Industry Murals, were originally commissioned for only 2 murals on the North and South walls. The original budget of $10,000 (worth $240,000 today) was doubled to $20,899 ($500,000 today) when all four walls were made part of the project. This was the fee paid to Rivera – the cost of materials and plastering was extra. The East and West walls have smaller surfaces.

Diego M. Rivera, Detroit Industry Murals, 1932-1933 (Detroit Institute of Arts, Gift of Edsel B. Ford)

In preparation for his work, in the summer of 1932, Rivera toured Ford’s River Rouge complex, where Ford began manufacturing in 1918. The complex now covers nearly 16 million square feet (1.5 km2) of factory floor space. At first, Ford made anti-submarine boats for WWI, and after the war, the manufacture of Ford’s Model A cars started in the late 1920s; now, the facility makes Ford F-150 pickup trucks. The last car, a red Mustang, rolled off the assembly line in 2004.

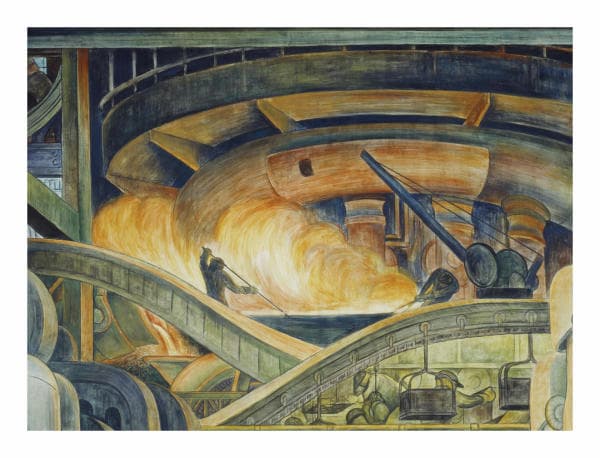

Rivera chose industry as his theme. Surrounded by Depression-hit Detroit, Rivera used the ‘marvel of the modernistic and high-tech River Rouge complex and its impact on workers’. The technology of the assembly line, the flow of the factory, and, with them, ‘the tension on the determined faces of workers caused by performing the string of repetitive tasks at maximum speed’.

Diego M. Rivera, Detroit Industry Murals: North Wall, 1932-1933 (Detroit Institute of Arts, Gift of Edsel B. Ford)

Diego M. Rivera, Detroit Industry Murals: South Wall, 1932-1933 (Detroit Institute of Arts, Gift of Edsel B. Ford)

On commission from the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, American composer Michael Daugherty wrote his symphony Fire and Blood, which was given its premiere by the orchestra on 3 May 2003, under the baton of Neeme Jarvi, with Ida Kavafian as solo violinist.

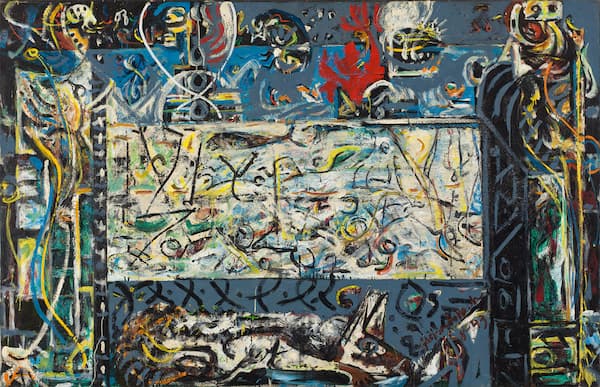

Michael Daugherty

Inspired by Rivera’s work, Daugherty calls his piece his ‘own musical fresco for violin and orchestra’. Rivera also saw the possibility of music in his art, saying after returning from a visit to the factory, “In my ears, I heard the wonderful symphony which came from his factories where metals were shaped into tools for men’s service. It was a new music, waiting for the composer…to give it communicable form.”

We start the first movement in Mexico City, surrounded by volcanoes. The erupting fire of the natural volcanoes is matched by the fires of the factory furnaces. The violinist is taxed with triple stops and closes the work with an extended cadenza, accompanied by marimba and maracas.

Diego Rivera: Detroit Industry, blast furnace and open hearth furnace (north wall mural detail), 1932-1933

(Detroit Institute of Arts, Gift of Edsel B. Ford)

Michael Daugherty: Fire and Blood – I. Volcano (Ida Kavafian, violin; Detroit Symphony Orchestra; Neeme Järvi, cond.)

The second movement, River Rouge, takes the life of Rivera’s third wife, Frida Kahlo (1906–1954), as a counterpart to the industrial activities. Kahlo was in constant pain from childhood polio and a bus accident at age 18, and her life of discomfort led to the Blood side of Daugherty’s work. There’s much of the artists’ native Mexico in Daughtery’s music in his melodic writing and in the use of marimbas in the background. Kahlo was with Rivera in Detroit and was frequently at the DIA site.

Michael Daugherty: Fire and Blood – II. River Rouge (Ida Kavafian, violin; Detroit Symphony Orchestra; Neeme Järvi, cond.)

It’s in the last movement that Daugherty takes on the immensity of the Rouge River plant with Assembly Line. Rivera’s own description of his murals detailed their “towering blast furnaces, serpentine conveyor belts, impressive scientific laboratories, busy assembly rooms; and all the men who worked them all”. The violinist represents the worker, surrounded by a mechanical orchestra. The percussion section includes metal instruments such as brake drums. In a larger sense, Daugherty says, “the musical phrasing recalls the undulating wave pattern that moves from panel to panel in Rivera’s mural”.

Michael Daugherty: Fire and Blood – III. Assembly Line (Ida Kavafian, violin; Detroit Symphony Orchestra; Neeme Järvi, cond.)

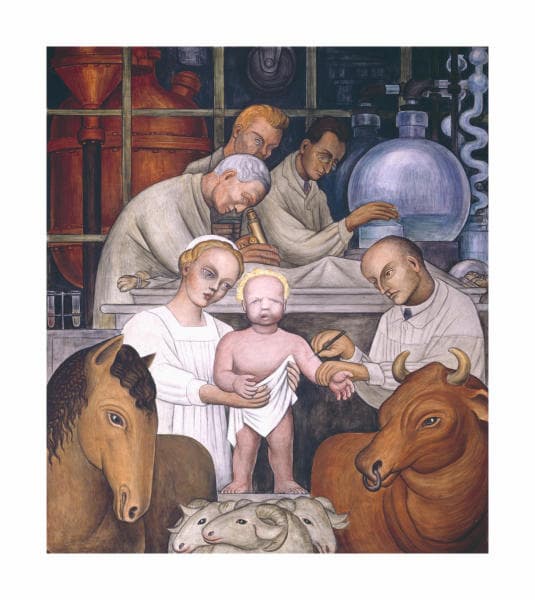

Considered one of the greatest of Rivera’s murals and ‘one of the country’s finest, modern monumental artworks devoted to industry’, the Detroit Industry Murals were not without controversy. In one corner, dedicated to the idea of vaccination, we have a very strange compilation.

Diego Rivera: Detroit Industry, Vaccination (north wall supporting panel), 1932-1933

At first glance, it’s a lovely nativity scene: Mary, Joseph, baby Jesus, with three wise men in the background. Or, if you know your images, it’s movie star Jean Harlow as Mary, the kidnapped Lindburg baby as Jesus, and DIA director William Valentiner as Joseph, who is vaccinating the child to protect its future. The three wise men are an ecumenical gathering of a Catholic, a Protestant, and a Jewish scientist.

So much of Rivera put into the Detroit Industry series was a positive view of the future. Not today’s Depression (which would last from 1929 to 1939, redeemed only by WWII and its industry demands) but the marvel of the modern – new manufacturing techniques, new medical advances, and the contribution of the world’s workers. He never forgets the role of the common man in the advances upon tomorrow, but he’s in praise of what tomorrow might bring. In his music, Daugherty brings us Mexican melodies and a driving American workforce, just as Rivera did in art.

There’s much more to the art than we’ve been able to cover here, so explore these murals at the DIA site.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter