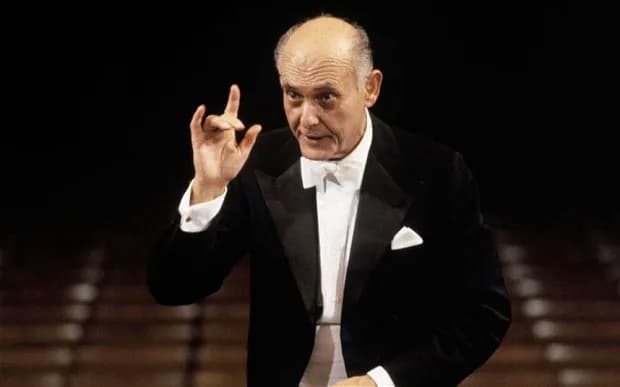

Sir Georg Solti was probably best known for his appearances with opera companies in Munich, Frankfurt, and London, and as a long-serving music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. He was also famous for his exuberant and forceful podium personality, which critics found both glorious and vulgar but never dully. Fastidious in the recording studio in search of technical accuracy, Solti was widely hailed for his ability to convey deeply felt emotions. His legacy includes over 250 Decca recordings, including 45 complete operas, and he has garnered 32 Grammy Awards.

Georg Solti Conducts Chicago Symphony

György Stern

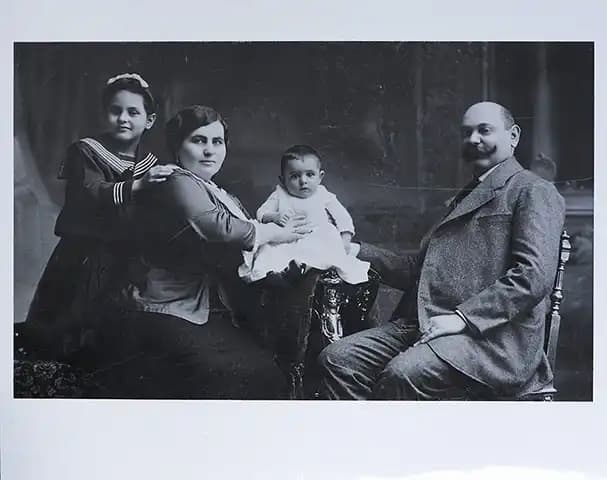

Georg Solti (baby) with his family

Georg Solti was born György Stern in Vérmezö Street, in the Hegyvidék district of the Buda side of Budapest, on 21 October 1912. His father Móricz “Mor” Stern had moved to Budapest as a young man. Solti describes him as “a sweet person but utterly untalented at business… he trusted everyone and was often cheated.” For his children, Mor Stern followed a requirement in the aftermath of World War I to change foreign-sounding names into Hungarian ones. As such, he renamed his children after Solt, a small town in central Hungary.

His mother Teréz Rosenbaum hailed from a region between the Danube and the Tisza rivers. Her family included the painter, photographer and co-founder of the Bauhaus, Moholy-Nagy, who later helped establish the Chicago Art Institute school. His mother’s youngest brother, later known as Emery Reeves, published Churchill’s memoirs and assembled an important collection of paintings. Teréz married “Mor” when she was still in her mid-teens, and Solti’s sister Lilly was born in 1904.

Richard Strauss: Salome – Scene 4: Ah! Du wolltest mich nicht deinen Mund kussen lassen, Jochanaan! (Birgit Niilsson, soprano; Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra; Georg Solti, cond.)

Early Memories

Georg Solti at age 4

Solti’s earliest memories were of a religious nature. His father kept all the Jewish traditions, including praying every morning and attending services at the synagogue every Friday evening and Saturday morning. As Solti remembered, “He used to take me with him, but I never stayed in the synagogue for longer than 10 minutes, which often upset him.” And in later years he recalled, “although both sides of my family were religious, I was never forced to practise the Jewish faith. I did not really rebel against it, but then, I disliked organized religion.”

Teréz Rosenbaum was highly musical, and she quickly noticed that her son had a very good ear. She decided that it was time for György to take piano lessons. The harpist of the Budapest Opera was engaged to come to the house once a week. Solti remembers, “I hated him because he hit my fingers when I made mistakes or disobeyed. What was worse, the piano was near a window, and while I was having a lesson or practising, I could see my friends playing soccer in the park… So my piano playing stopped almost as soon as it had begun.”

Georg Solti Conducts Wagner’s Götterdämmerung, “Siegfried Funeral Music”

Music Revival

Georg Solti as a teenage

When György entered his second year at elementary school, he discovered his love for singing. He also knew that he could do a better job than the boy who played the piano accompaniments. “He awakened my tremendous musical ambition, which has never subsided to this day.” As such, he started piano lessons again, with his mother believing that he had the makings of a musician. Apparently, she resisted the advice of her husband and one of her brothers to make him learn a “real profession.”

A new teacher was found, and when György reached the age of 10, he passed the entrance examination for the Ernő Fodor School of Music. It was a high-profile private institution, and György studied with Miklós Laurisin. As he remembers, “He was the first teacher who told me that sound is not only produced by the fingers, and he loved to teach. I was grateful to him for what he taught me; sad to say, he later became a Nazi sympathiser, and I lost all contact with him.”

Béla Bartók: Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta, BB 114 (Chicago Symphony Orchestra; Georg Solti, cond.)

Liszt Academy

Georg Solti

After two years at the Fodor School, György passed the entrance exam for the Liszt Academy, “where, for six years, I received the most significant part of my formal musical education… The training I received was difficult and at times harsh, but those who survived the experience emerged as real musicians.” His first piano teacher, Arnold Székely, came from a line of pianists who had studied with Liszt. Apparently, Székely was not a great teacher, and when he caught pneumonia, the class was taken over by Béla Bartók.

Bartók, for Solti, “presented an austere, forbidding front to the world, and his reputation was daunting. He was widely regarded as a raving radical, but we music students knew exactly how important he was, and we revered him.” Solti remembers making an awful faux pas during one of the first lessons. “I sat down to play his Allegro barbaro. When he saw me set the music on the stand, he became quite upset and said No, no, not that. I don’t want to hear that. It was stupid of me to have thought that he might have enjoyed hearing an immature student play one of his compositions, but my intentions had been good; I had wanted to show my love and respect for him.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter