In April 1919, Gabriel Fauré’s Masques et Bergamasques, a comédie musicale, with a libretto by René Fauchois, had its debut at the Opéra de Monte-Carlo. From its very title, the influence of Italian commedia dell’arte, French music, and pastoral art is apparent.

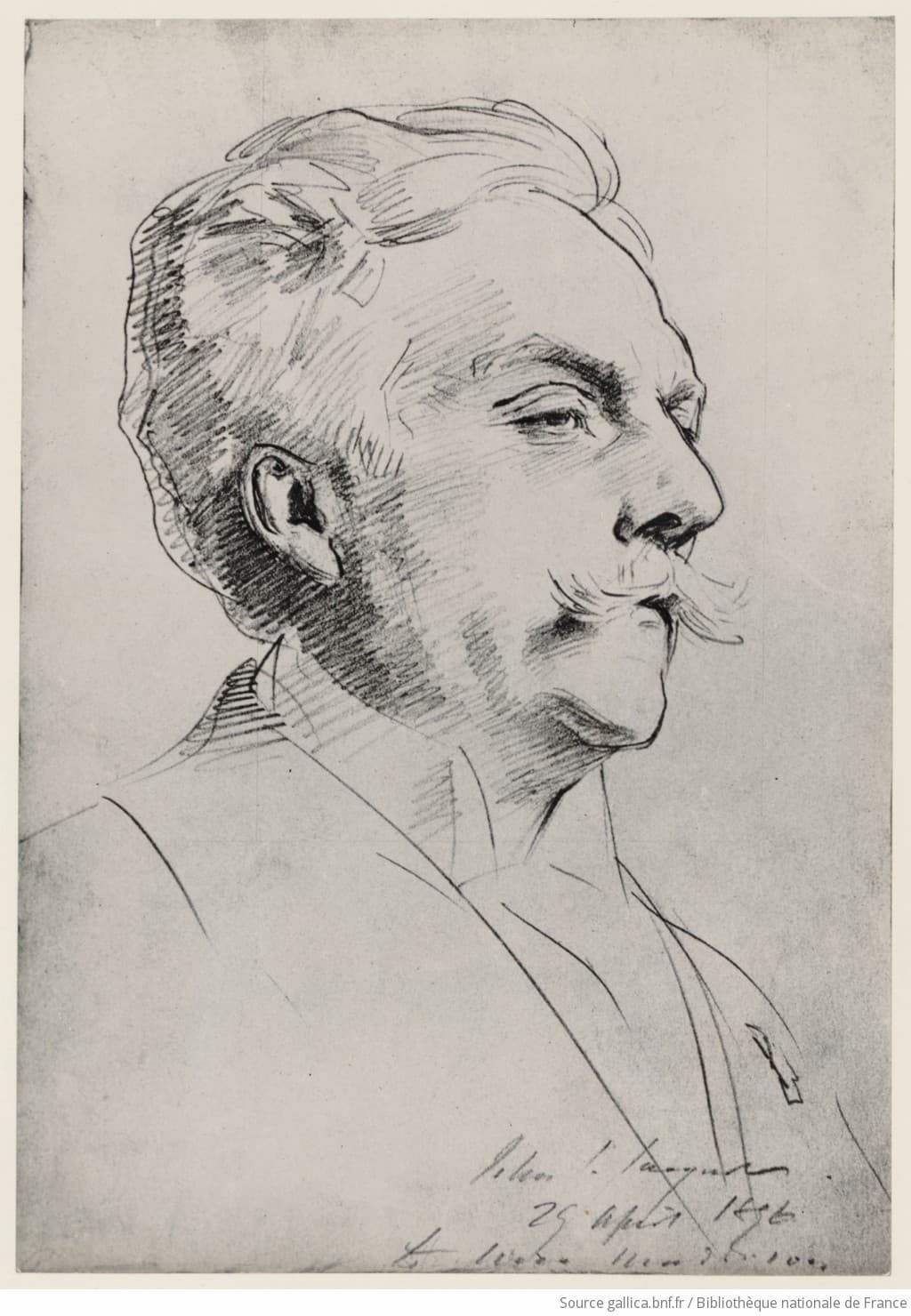

John Singer Sargent: Gabriel Fauré

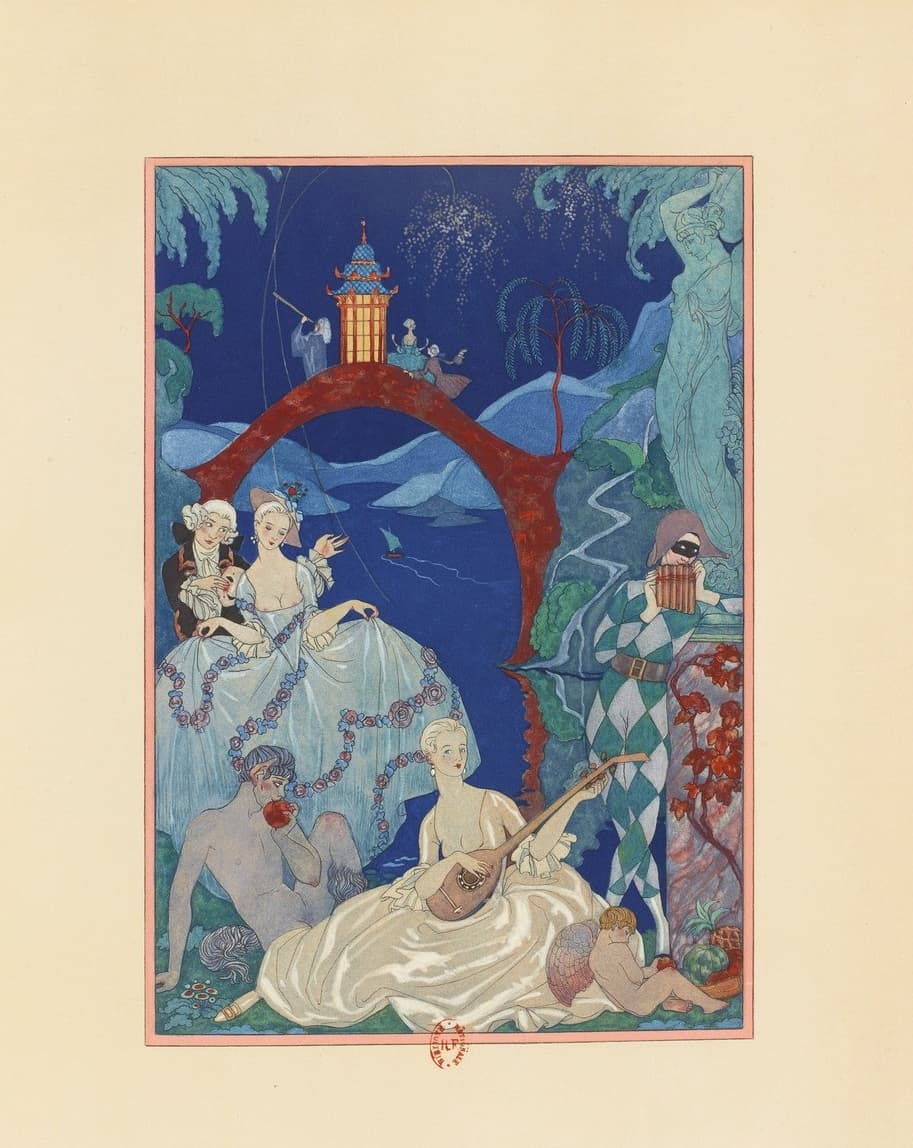

Verlaine’s 1869 poetry collection, Fêtes galantes, was the source for Fauchois’ characters.

George Barbier: Claire de lune from Verlaine’s Fêtes galantes, 1928 (Gallica:ark:/12148/bpt6k15213572)

The work was commissioned by Prince Albert I of Monaco to accompany a choreographic divertissement. Fauré constructed his score from both new music and older scores.

The story starts with the commedia dell’arte characters Harlequin, Gilles, and Columbine in the countryside on a ‘Cytherian island’. Next, a theatre audience of ‘figures from the aristocratic world of Watteau…’ arrive. The scenery was based on Watteau’s The Swing.

Watteau: The Swing, 1712 (Helsinki: Sinebrychoff Art Museum)

The setting of an idyllic and imagined elegance was evoked both by the Watteau imagery and by Verlaine’s poetry, who looks back at Watteau’s images with fond remembrance. The title of the work comes from Verlaine’s poem Clair de lune:

Votre âme est un paysage choisi

Que vont charmant masques et bergamasques

Jouant du luth et dansant et quasi

Tristes sous leurs déguisements fantasques.

Your soul is a chosen landscape

Charmed by masks and bergamasques

Playing the lute and dancing and almost

Sad under their fanciful disguises.

The title of the work, of course, is a pun on the masque, an entertainment based around a masked ball, and the bergamasque, a dance from Bergamo, since the work was for a choreographic divertissement.

Shortly after the staged presentation, Fauré put together four movements from the larger work to create the Masques et bergamasques Suite, Op. 112, with the songs from the original work transformed into orchestral music and dances without singers or dancers.

The work starts with a lively dancing overture, and in your mind’s eye, you can see the stage filling with both the commedia dell’arte characters and the audience.

Gabriel Fauré: Masques et bergamasques Suite, Op. 112 – I. Ouverture (Lausanne Chamber Orchestra; Renaud Capuçon, cond.)

The second movement is a Menuet, a dance of the upper classes, and the music changes to reflect the sudden formality on stage. Unlike symphonic menuets, there is no separate trio section.

Gabriel Fauré: Masques et bergamasques Suite, Op. 112 – II. Menuet (Lausanne Chamber Orchestra; Renaud Capuçon, cond.)

The Gavotte is a lighter movement, with the orchestral line emphasized by timpani beats.

Gabriel Fauré: Masques et bergamasques Suite, Op. 112 – III. Gavotte (Lausanne Chamber Orchestra; Renaud Capuçon, cond.)

The closing Pastorale seems to signal sunset on the island.

Gabriel Fauré: Masques et bergamasques Suite, Op. 112 – IV. Pastorale (Lausanne Chamber Orchestra; Renaud Capuçon, cond.)

Even Fauré commented on the music as having ‘a somewhat evocative and melancholy – even nostalgic – character. It’s like the impression you get from the paintings of Watteau. Verlaine once described it as “playing the lute and dancing yet appearing rather sad beneath fantastic disguises”’. Fauré’s reuse of earlier music included the music for the first three movements, which was, in fact, based on piano pieces he’d written almost 50 years earlier.

Masques et bergamasques becomes a triple imagining of the past: Watteau’s paintings from the early 18th century, Verlaine’s look back at the world of Watteau and writing his Fêtes galantes in that style, and then Fauré’s music, which not only included Watteau’s and Verlaine’s ideas and feelings but also looks back half a century to his own earlier music. It’s a lovely work that has the ability to call up our own feelings of nostalgia and a happy past.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter