For many literary critics, the Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen (1828-1906) is considered “the father of realism and the second most influential playwright of all times.” Ibsen was one of the founders of modernism in theatre and completely rewrote the rules of drama.

Edvard Grieg: Peer Gynt Suite No. 1, Op. 46 “Morning Mood” (New York Philharmonic Orchestra; Leonard Bernstein, cond.)

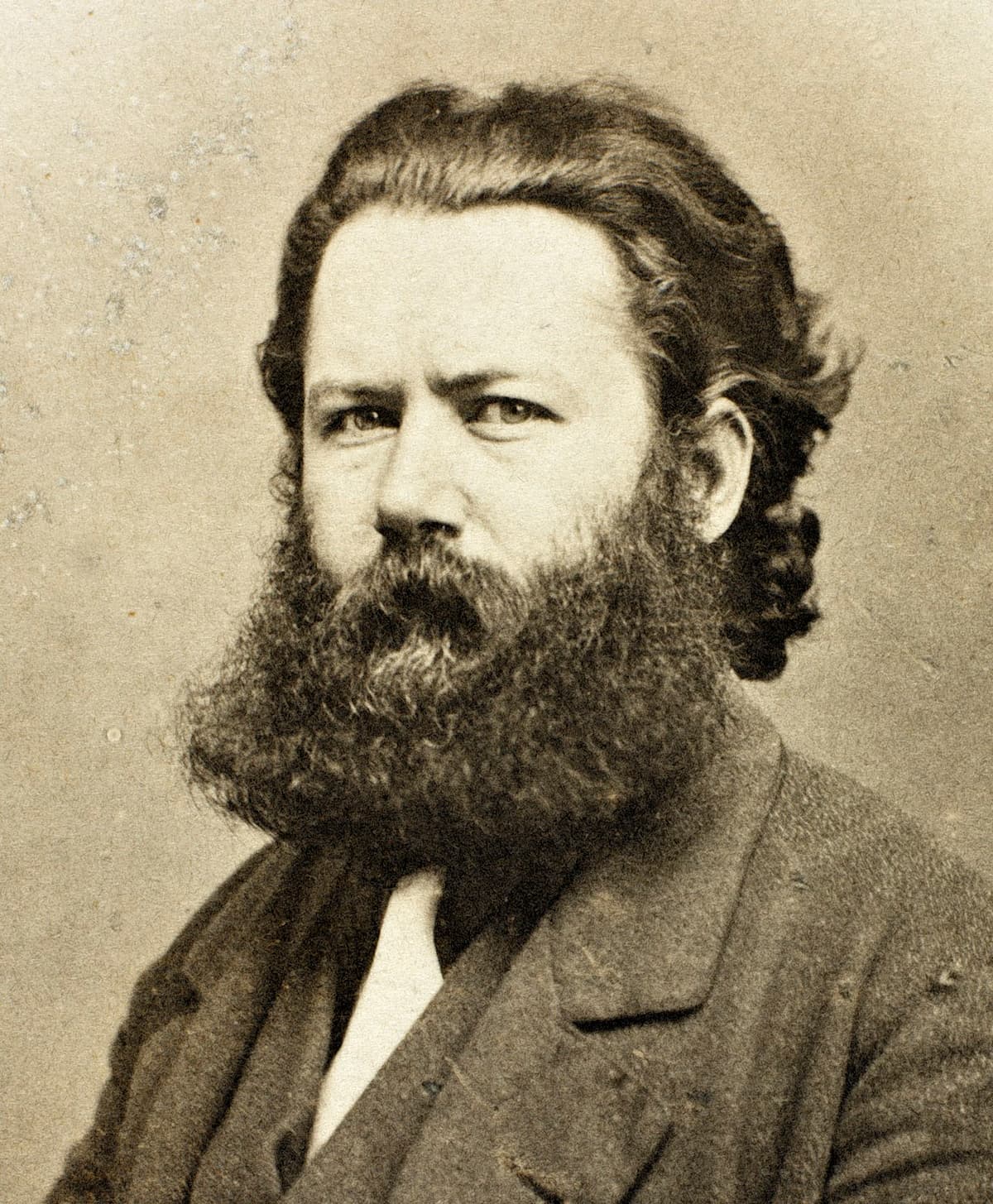

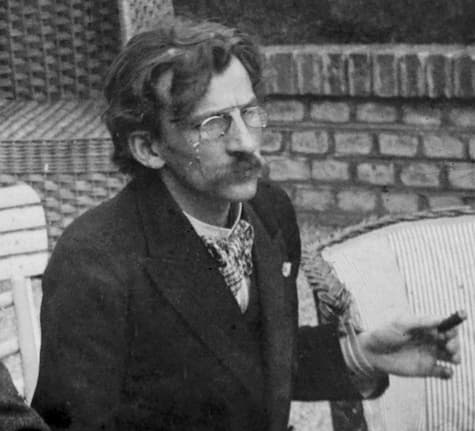

Portrait of Henrik Ibsen

Ibsen brought his audience into regular people’s homes, where the bourgeois kept their carefully guarded secrets. “He then placed the conflicts that arose from challenging assumptions and direct confrontations against a very realistic middle-class background and developed them with piercing dialogue and meticulous attention to detail.”

“If you take away the average man’s life-lie,” Ibsen writes in The Wild Duck “you take away his happiness at the same time.” Ibsen certainly gained notoriety with his play A Doll’s House, in which the character of Nora is leaving her husband Torvald and her three children. It caused a scandal in 1879 when it was first performed, “and it is still considered one of the most famous gender political moments in world literature.”

Edvard Grieg: Peer Gynt Suite No. 1, Op. 46 “The Death of Aase” (New York Philharmonic Orchestra; Leonard Bernstein, cond.)

That play, with its emphasis on the social problem of women’s status in marriage, gave Ibsen a reputation as a playwright of ideas and a feminist. Near the end of his life, however, Ibsen said that he had “been more of a poet and less of a social philosopher than people have generally been inclined to believe.” In fact, Ibsen’s career is marked by a tension between the poet and the social philosopher.

However, Ibsen had a different philosophy at the early stages of his career. At the age of 36, Ibsen left Norway for Rome and wrote Brand and Peer Gynt, both in verse and following in the tradition of European romantic drama. Both plays immediately made him famous in Europe. Both plays turn on the conflicts between duty and pleasure and are filled with larger-than-life characters, mythical elements, and supernatural intervention, “which greatly inspired later symbolist and avant-garde playwrights.”

Edvard Grieg: Peer Gynt Suite No. 1, Op. 46 “Anitra’s Dance” (New York Philharmonic Orchestra; Leonard Bernstein, cond.)

Henrik Ibsen’s Peer Gynt

Ibsen sent parts of his Peer Gynt manuscript to his publisher, explaining the work’s starting point. “Peer Gynt was a real person who lived in the Gudbrandsal, probably around the end of the last century or the beginning of this one… Not much more is known about his doings than you can find in Asbjørnsen’s Norwegian Fairy Tales… So I haven’t had much on which to base my poem, but it has meant that I have had all the more freedom with which to work on it.”

In the end, the five-act verse play presents a meandering tale about an anti-hero, “with no ruling passion, no calling, no commitment, the eternal opportunist, the charming, gifted, self-centred child who turns out finally to have neither centre nor self.”

Edvard Grieg: Peer Gynt Suite No. 1, Op. 46 “In the Hall of the Mountain King” (New York Philharmonic Orchestra; Leonard Bernstein, cond.)

In 40 scenes, the title character has one disastrous adventure after another. He attends the wedding of a wealthy young woman he himself might have married. There, he meets Solveig, who falls in love with him. However, Peer impulsively abducts the bride from her wedding celebration and subsequently abandons her.

He embarks on a series of fantastic voyages around the world, finding wealth and fame but never happiness. As he arrives back in Norway for a hallucinatory finale in which he is faced with the strands of his life that have gone awry, he is redeemed by Solveig, ever faithful and loving.

Edvard Grieg: Peer Gynt Suite No. 2, Op. 55 “Ingrid’s Lament” (English Chamber Orchestra; Raymond Leppard, cond.)

Edvard Grieg’s Peer Gynt Suite No. 1 – Morning Mood

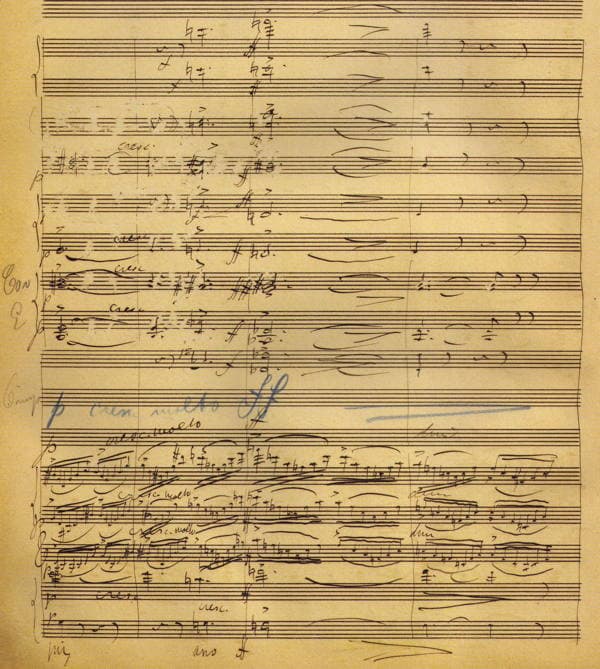

Ibsen met Grieg in Rome in 1866 but never really became good friends. The stage play of 1867 was considered a modest success, but it was produced in Christiania with accompanying music by Grieg over a decade later. Ibsen had written from Italy to ask Grieg to provide music for the production, and the composer had accepted.

Grieg had misjudged the amount of music that would be required, and he wrote to a friend in 1874, “Peer Gynt goes very slowly. It is a horribly intractable subject except for a few places… And I have something for the hall of the troll-king that I literally can’t bear to listen to; it reeks so much of cow-pads and super-Norwegianism.”

Edvard Grieg: Peer Gynt Suite No. 2, Op. 55 “Arabian Dance” (English Chamber Orchestra; Raymond Leppard, cond.)

Ibsen had little feeling or sense for music, although he wrote some opera criticism, expressing strong views on librettos. In 1861, he attempted to rewrite his Olaf Liljenkrans for the operatic stage, but the project was quickly abandoned. He also turned down a request for a libretto from Grieg.

In the end, Grieg wrote 26 different numbers for Peer Gynt, totalling about 90 minutes of music. Neither Ibsen nor Grieg attended the premiere, but the production was a triumphant success. Grieg was still not happy as the theatre had not given him specifications as to the duration of each number and its order. As he writes, “I was thus compelled to do patchwork… In no case had I the opportunity to write as I wanted.”

Edvard Grieg: Peer Gynt Suite No. 2, Op. 55 “Peer Gynt’s Homecoming” (English Chamber Orchestra; Raymond Leppard, cond.)

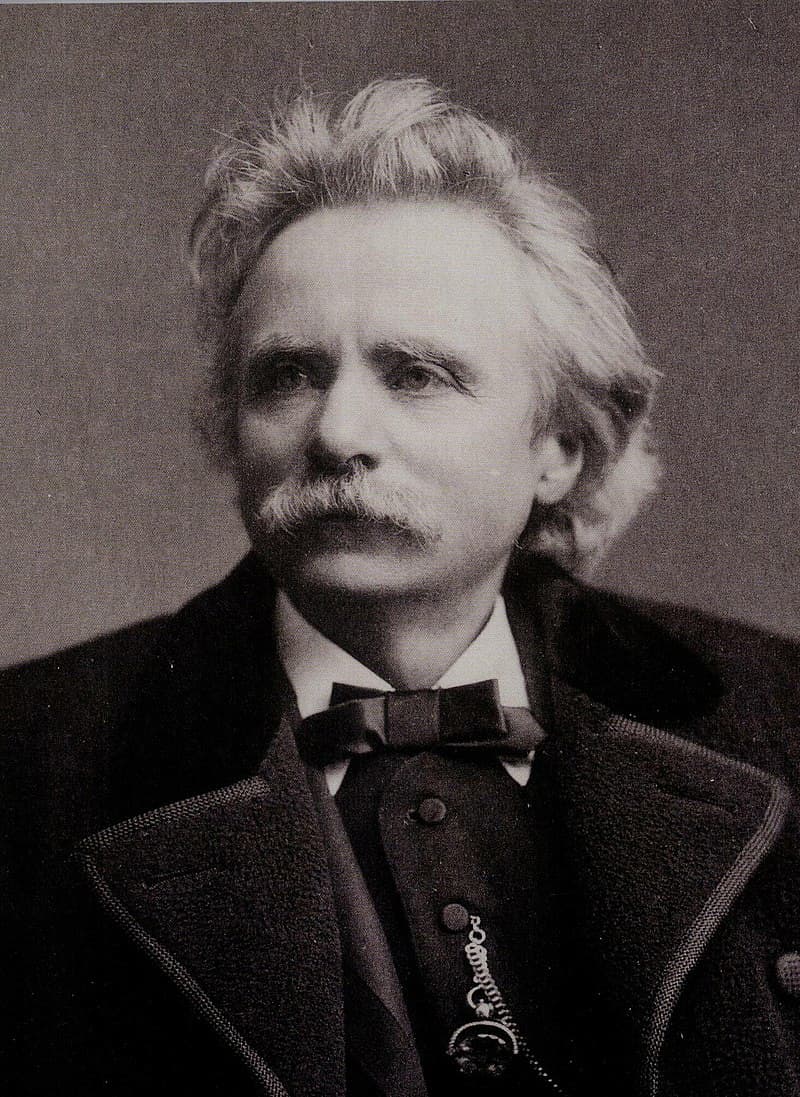

Edward Grieg, 1888 (Bergen Public Library)

The complete score of the incidental music includes several songs and choral pieces. It was believed to have been lost until the 1980s and has only been performed in its entirety since then. Of course, we know that a decade after composing the full incidental music, Grieg extracted eight movements to make two four-movement suites.

The Suites contain some of Grieg’s best-known music, with Suite No. 1 being the far more famous. For many decades it was a staple of music education curricula for the young. For Grieg it meant international fame and financial security, and his music has completely overshadowed Ibsen’s play. The music, as we can easily hear, is evocative and dramatically relevant, the story messages resonating in no small measure through the power of Grieg’s memorable score.

Edvard Grieg: Peer Gynt Suite No. 2, Op. 55 “Solveig’s Song” (English Chamber Orchestra; Raymond Leppard, cond.)

While most music lovers know the Peer Gynt Suites by Edvard Grieg, the stage music for Ibsen’s fairytale drama “The Feast of Solhaug” by Hans Pfitzner (1869-1949) is relatively unknown. The musical score dates from the years 1889 and 1890, and underscores Ibsen’s first publicly successful drama. Written in 1855 and first performed at the Theater in Bergen on 2 January 1856, the play was received enthusiastically.

The play centres on Margit, a woman in a good marriage with a wealthy and good man, essentially the “Mountain King.” She has everything she could ask for except love and adventure. Her quest for complete happiness arrives in the form of the kinsman and former flame Gudmund Alfson. As he is basically an outlaw, Margit imagines that he can provide the adventure and excitement she is missing.

Hans Pfitzner: The Feast at Solhaug, Act I “Prelude” (Cologne West German Radio Orchestra; Helmut Froschauer, cond.)

Hans Pfitzner

Gudmund is a gentle but heroic character, and on finding Margit married, transfers his affections to her younger sister Signe. There is a predictable complication, however, as Signe is also pursued by the King’s sheriff Knut Gesling. These misreadings of feelings and misunderstandings occur on the night of a feast to celebrate the anniversary of Margit’s unhappy marriage.

Amongst the frivolities are threats of infidelity, betrayal and murder, and the only light relief is brought by Margit’s oblivious husband Bengt, who, aware of his wife’s unhappiness is nevertheless determined to enjoy the festivities by drinking himself into oblivion.

Hans Pfitzner: The Feast at Solhaug, Act II “Prelude” (Cologne West German Radio Orchestra; Helmut Froschauer, cond.)

When Pfitzner presented his music to the Stuttgart publisher Luckardt in 1903, he described the work as a “kind of audio guide to the play.” The programmatic character of Pfitzner’s music is ever-present, and all three parts closely imitate the setting and atmosphere of Ibsen’s text.

The yearning of Margit, imprisoned in the Mountain King’s realm, is musically expressed in a probing motif, while the coming of spring is represented by a pastoral sicilano. Feelings of longing are depicted by a quickening of the tempo, as the magnificent “Mountain King” theme finally sounds to full effect.

The second part of the play is characterised by festive dance and merriment, with the composer turning to dancing rhythms and a great variety of tempos. The concluding third part “again shows the music faithfully following the line of the plot, once again quoting the emotional Mountain King theme in the context of hopes and feverish fantasies and expressing the state of waking by means of a progressive brightening of the music.” You might know that Hugo Wolf also wrote incidental music to “The Feast at Solhaug,” but more on that in a later article.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Hans Pfitzner: The Feast at Solhaug, Act III “Prelude” (Cologne West German Radio Orchestra; Helmut Froschauer, cond.)