In November 1792, Beethoven was sent by his patron, the Archbishop-Elector of Bonn, to Vienna, where he would study with Haydn. To show his pupil’s progress, Haydn reported back to the Archbishop-Elector, sending examples of his work.

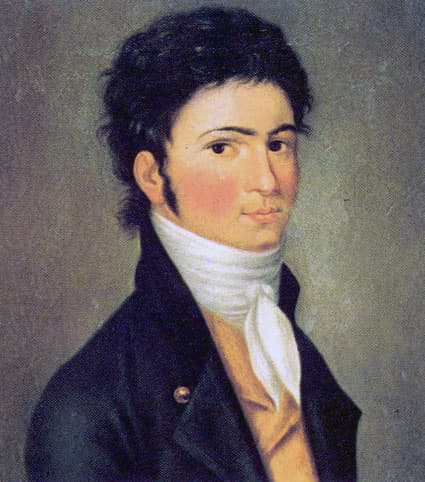

Riedel: Beethoven, 1801

Unfortunately, one of the works he sent was Beethoven’s Wind Octet, along with a plea for some additional funds. The brisk reply from the Elector was that the Octet had, in fact, been composed before Beethoven left Bonn, and perhaps it was time for Beethoven to return home.

The Octet in E flat major, later given the opus number 103, was for pairs of oboes, clarinets, horns, and bassoons and had been written for the Elector’s wind ensemble. The ensemble played during the Elector’s meal times. The wind band, called the ‘harmonie’, was first popularized by the one in the imperial court, and the smaller courts in the Habsburg empire followed suit. The ensembles were inexpensive to maintain, cost less than an orchestra, and yet had enough sound power to provide music for spacious rooms or for open-air activities. In a sense, it was music to be ignored, background music in the truest sense.

The key of E flat was particularly suitable for wind ensemble, and this is unrelated to how Beethoven used the key in his more heroic works, such as his Eroica Symphony or the Fifth Piano Concerto.

The Archbishop-Elector’s ensemble had grown with time to include the latest wind instruments, such as the clarinet, and Beethoven’s instrumental writing rose to the occasion. The long-established oboes take precedence in the first movement, being given a significant motive.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Octet in E-Flat Major, Op. 103 – I. Allegro (Stephen Taylor and Hsuan-Fong Chen, oboes; David Shifrin and Paul Wonjin Cho, clarinets; Frank Morelli and Marissa Olegario, bassoon; William Purvis and Lauren Hunt, horns)

In the second movement, the oboe and the bassoon share the lead.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Octet in E-Flat Major, Op. 103 – II. Andante (Stephen Taylor and Hsuan-Fong Chen, oboes; David Shifrin and Paul Wonjin Cho, clarinets; Frank Morelli and Marissa Olegario, bassoon; William Purvis and Lauren Hunt, horns)

The third movement Menuetto, is more like Beethoven’s later Scherzo movements and less like the traditional dance movement. The contrasting Trio section, lighter in feeling, brings the clarinet forward against the horns. The movement back to the Menuetto section starts gradually.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Octet in E-Flat Major, Op. 103 – III. Menuetto (Stephen Taylor and Hsuan-Fong Chen, oboes; David Shifrin and Paul Wonjin Cho, clarinets; Frank Morelli and Marissa Olegario, bassoon; William Purvis and Lauren Hunt, horns)

The final movement is a lively Presto, showing off the skills of each of the Octet instruments.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Octet in E-Flat Major, Op. 103 – IV. Finale: Presto (Stephen Taylor and Hsuan-Fong Chen, oboes; David Shifrin and Paul Wonjin Cho, clarinets; Frank Morelli and Marissa Olegario, bassoon; William Purvis and Lauren Hunt, horns)

This work, completed in 1792, was not published until 1830, so it received Opus 103 instead of a relatively low opus number.

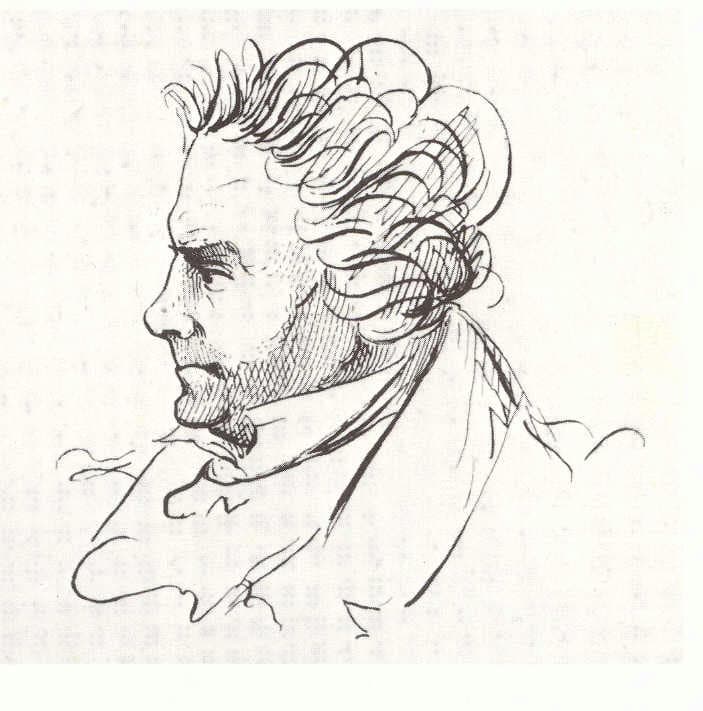

Lyser: Beethoven Caricature, 1825

Beethoven’s works weren’t given opus numbers until his first publications in 1795 in Vienna. The high opus number hid the fact that this was a youthful work. His Op. 104, a String Quintet, wasn’t written until 1815, for example. The publisher was seeking to place this work as something from the mature Beethoven, rather than an incidental work from his early years.

In the end, the double lie (I wrote this while studying with Haydn in Vienna and This is a mature work) was exposed but the work still holds a certain charm.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Op. 104 was a string quintet arrangement by Beethoven of his Piano Trio in C Minor, Op. 1, No. 3, which he (very justifiably, I would say) maintained a strong affection for through his years.