The French Revolution was the dramatic backdrop to countless extraordinary life stories. Pianist and composer Hélène de Montgeroult had one of the most interesting.

Over the course of her life, she faced political turmoil, violence, and unspeakable loss, but persevered and ended her career as a widely respected pedagogue and performer.

Today, we’re taking a look at the life and music of Hélène de Montgeroult.

Hélène de Montgeroult’s Childhood

Hélène de Montgeroult

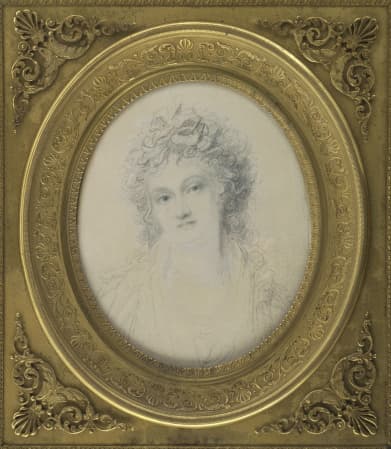

Hélène de Montgeroult was born Hélène de Nervo on 2 March 1764 in Lyon to unlanded nobility. Her paternal grandfather had bought a title, and her father had inherited a title and court position.

As a girl, she spent time in Paris and studied music there. Her keyboard teachers may have included celebrated Czech pianist and composer Jan Ladislav Dussek. He has since been acknowledged as a crucial link between the Classical and Romantic eras – something that Hélène has also been called.

Jan Ladislav Dussek- Piano Concerto in G minor, Op 49 | Vitam Musica Chamber Orchestra

Hélène de Montgeroult’s Marriage and Early Career

In 1784 Hélène married Marquis André Marie Gautier de Montgeroult, a man nearly thirty years her senior, and made a home with him.

Given her social rank, she did not perform piano publicly. However, she did play at prestigious salon concerts in her home and in other aristocrats’ homes, at concerts that were attended by the wealthiest and most influential Parisian figures. These figures included painter Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, author Germaine de Staël (daughter of the influential French finance minister Jacques Necker), and violinist Giovanni Battista Viotti.

Hélène and her husband were, like many aristocrats of the era, constitutional monarchists. They saw a need for the excesses of the monarchy and aristocratic class to be reigned in and a desire to emulate Enlightenment attitudes about human rights but had a limited appetite for violent wholesale change to the societal order.

The French Revolution: Widowhood and Mortal Danger

Château de Montgeroult

In July 1792, Hélène and her husband left France with statesman Hugues-Bernard Maret. These were tense weeks that would prove pivotal to French history. The following month, the King and his family were arrested. France was a veritable tinderbox, and all that was needed was a match to spark the flames of a full-blown revolution.

Laws were passed regarding the confiscation of property of emigrants, so Hélène and her husband returned to France in December. A few weeks later, in January 1793, Louis XVI was guillotined.

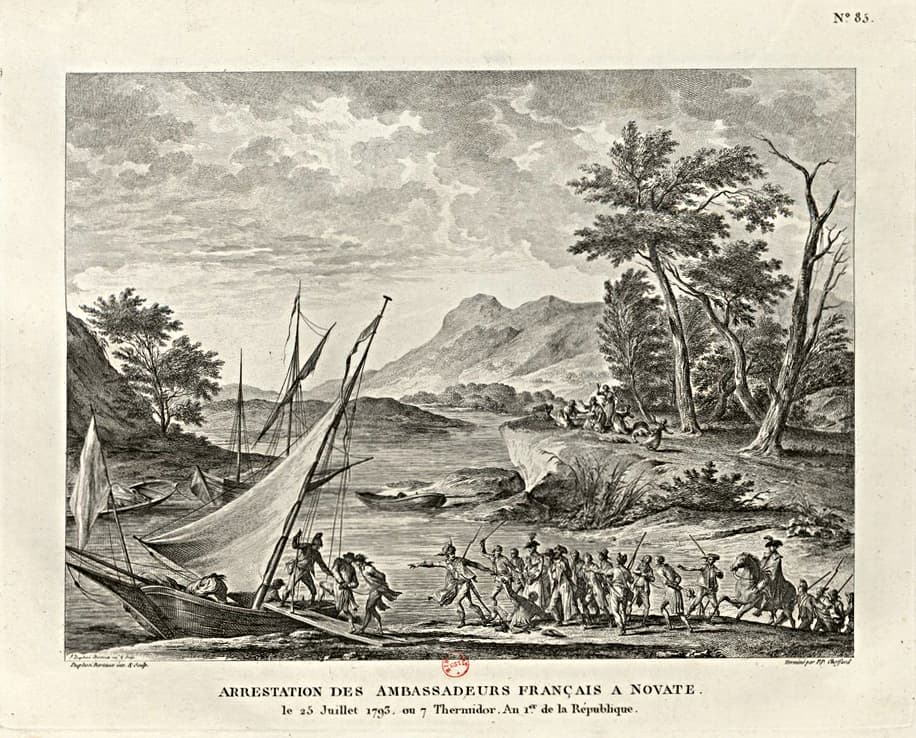

The following summer, Hélène and her husband left France a second time, again accompanying Maret, who had just been named Ambassador to Naples. One of the issues they hoped to address was getting help to save the life of Queen Marie Antoinette.

As soon as France had fallen into chaos, all of Europe quickly recognized that a bloody French revolution was the perfect time to attempt to advance their own interests. Of all France’s enemies, Austria was among the bitterest.

Unfortunately, disaster struck when Hélène and her husband’s party was stopped in Lombardy by Austrian troops. The Austrians approached them, took the men prisoners, and beat the women and children with rifle butts.

Maret and her husband were imprisoned by the Austrians. In September 1793, her husband died in custody.

As for Hélène, she barely escaped with her own life. An account exists where she describes climbing walls and walking through marshes, all the while glancing behind her to make sure her husband’s captors weren’t coming back for her.

Hélène de Montgeroult – Sonata in A minor, Op. 2 No. 3

Simultaneously, the couple was subject to a denunciation back home in France. However, when news got back that her husband had been murdered by France’s enemy, once she was released by the Austrians, “Citizen Gaultier-Montgeroult” was allowed to return to Paris.

There is a legend that during the Terror, Hélène faced the prospect of execution but saved herself by improvising on La Marseillaise in front of the Revolutionary Tribunal. It’s not known whether this story is true or not, but even if it’s not literally true, it certainly speaks to an emotional truth of how alone and vulnerable she must have been feeling at this time and how central music was to her identity. And even if such a dramatic recital never took place, it remains true that her musical abilities are likely what saved her life.

A New Son, a New Husband, and a New Job

Arrest of the French Ambassadors

Not long after she became a widow, she started dating Charles Antoine-Hyacinthe His, an editor at Le Moniteur Universel, the main newspaper of the Revolution. She had a son named Horace His de la Salle in February 1795 out-of-wedlock. If His was the father, that obviously means they were in a relationship by the spring of 1794. Hélène married His in June of 1797. (They’d divorce a few years later.)

Hélène de Montgeroult – 7 Etudes

A few months after her son was born, the government established a Conservatoire for the education of French musicians. Officials sent out notice they were looking for harpsichord teachers.

Hélène was hired as a first-class teacher of the men’s piano class – and interestingly, her salary would be equal to the male teachers’. She was the first woman to teach at what would become the legendary Paris Conservatoire.

Unfortunately, her tenure there only lasted a couple of years, and it’s unclear as to why, although her resignation letter suggests it was, at least in part, ill health.

Hélène de Montgeroult’s Published Music and Legendary Salons

Also, in 1795, she published her Opus 1 – a set of three sonatas. It was the first of many works; she continued composing prolifically in the politically turbulent years to come.

She also worked for years and years on a piano method called the “Complete Method”, which was only published in 1820. It contained nearly a thousand exercises.

Making the Piano Sing: the music of Hélène de Montgeroult; Ian Buckle, piano

During this time, she combined her social status with her musical abilities, holding salons known as “Madame de Montgeroult’s Mondays.” She often played with the greatest musicians of the day, men like Viotti, Kreutzer, Cherubini, and others.

At these gatherings, her numerous luminous friends would get together to exchange news, ideas, and gossip. In this way, she helped to influence French politics and the development of French culture during the Napoleonic era.

Hélène de Montgeroult’s Later Life

Hélène de Montgeroult

At some point she was widowed. In 1820, she married Count Édouard Dunod de Charnage, who was nineteen years younger than she was. It must have seemed likely that he’d outlive her, but six years later, he died falling from a horse.

By this point, her health was deteriorating. She moved from France to Italy to be nearer to her son who had moved there and died in Florence on 20 May 1836. She was 72 years old.

Tragically, however, if there were any manuscripts or letters left in her son’s possessions, he destroyed them. To the best of our knowledge, none exists today.

Hélène de Montgeroult’s Legacy – and Future

It’s a tremendous shame that Hélène de Montgeroult’s works haven’t entered the repertoire.

That said, she seems to be a composer on the cusp of a renaissance. Her work has been recorded and championed more and more over the last couple of years. There’s even an hour-long documentary about her on YouTube now, too, which is great news for any new fans her music may attract.

After generations of unconscionable neglect, let’s hope that the remarkably talented Hélène de Montgeroult gets her dues from musicians and music lovers, and soon.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter