Franz Liszt (1811–1886) created the genre of the symphonic poem, but they weren’t without controversy. Eduard Hanslick, the premiere critic of mid–mid-19th-century Vienna thought little of them, noting that the addition of the extra-musical programmes did not justify what he saw as an absence of music content.

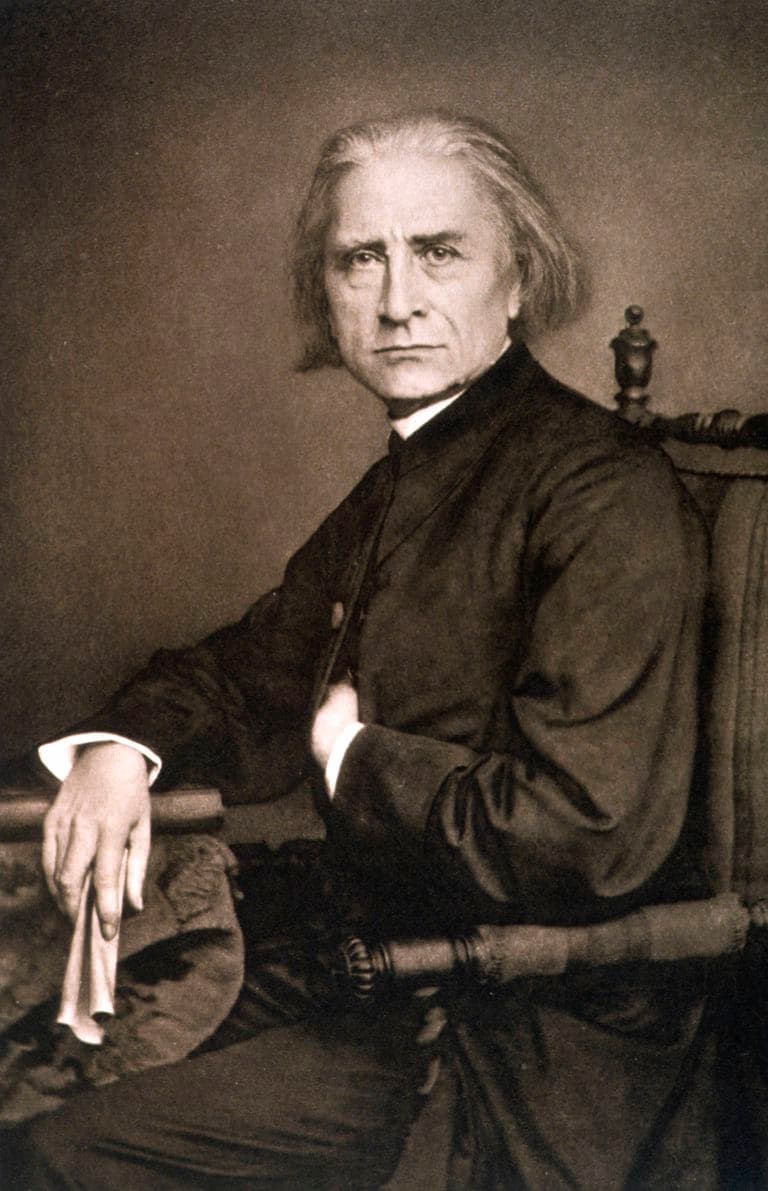

Franz Hanfstaengl: Liszt, 1870

Liszt became acquainted with Goethe’s telling of the Faust story in Paris in 1828 and fell in love with it immediately – for him, it was the equivalent of Dante’s La Divina Comedia, which he used as the basis for his Dante Symphony. It wasn’t until he was in Weimar, the home of Goethe and Schiller, however, that he took up the characters as subjects for his music.

Anton Kaulbach: Faust and Mephisto, ca. 1900

Starting with sketches and initial concepts in the 1840s, Liszt merged his symphonic poems with the symphony, completing the first version of his Faust Symphony of 1854. Using the characters for each of the movements gave him the opportunity to explore each of them in greater depth than he could in just a single-movement symphonic poem. The work was given its premiere on a particularly auspicious occasion: the dedication of Rietschel’s Goethe and Schiller Monument in Weimar on 5 September 1857.

Ernst Rietschel: Goethe and Schiller Monument in Weimar, 1857

A Faust Symphony opens with the eponymous scientist himself. Faust was a particular favourite for writers in the 19th century because he could be moulded in so many ways: he could be a human hero, a scholar who would do anything for youth and power, or even an opponent to political and religious tyrannies. For Liszt, he assumed the listener knew the Faust story and it didn’t need to be told. The characters were his focus, particularly their inner lives.

The character of Faust is multi-sided: he’s contemplative, erudite, passionate, and wants higher knowledge; he has a love of God and humanity but his pride becomes his downfall.

Franz Liszt: A Faust Symphony (Three Character Pictures, after Goethe) – Faust (Franz Liszt Academy of Music Orchestra; András Ligeti, cond.)

Gretchen, as the simple maid, has a much simpler character drawn in Liszt’s music: her innocence comes through in the lyrical melodies but doesn’t capture the depth of feeling she has for Faust as shown in works such as Schubert’s Gretchen am Spinnrade. Her melodies start in the flutes and clarinets and the overall setting is as for a small orchestra.

Ary Scheffer: Faust and Gretchen in the Garden, 1846

Franz Liszt: A Faust Symphony (Three Character Pictures, after Goethe) – Gretchen (Franz Liszt Academy of Music Orchestra; András Ligeti, cond.)

It is in the Mephistopheles movement that the devil gets his due. The music of Faust’s movement returns here but transformed and twisted. Gretchen’s music also returns but as a redeeming note. The convoluted fugue that precedes Gretchen’s theme is smoothed away.

Delacroix: Faust and Mephistopheles, 1827 (The Wallace Collection)

Franz Liszt: A Faust Symphony (Three Character Pictures, after Goethe) – Mephistopheles (Franz Liszt Academy of Music Orchestra; András Ligeti, cond.)

After completing the first three movements, Liszt waited another 3 years before he added the chorale finale. Tenor and chorus re-emphasize Gretchen’s victory: All transitory things are but a likeness…the eternal feminine draws us upward.

Friedrich Moritz August Retzsch: Die Schachspieler (private collection)

Franz Liszt: A Faust Symphony (Three Character Pictures, after Goethe) – Final Chorus (András Molnár, tenor; Hungarian State Opera Chorus; Franz Liszt Academy of Music Orchestra; András Ligeti, cond.)

In a sense, the symphonic poems that precede the Faust Symphony could be regarded as the preludes to the final picture. In answer to Hanslick’s objection to the symphonic poems as lacking musical substance, here Liszt has used the story as a springboard to the deeper exploration of the characters and puts the story aside in preference to the music.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter