A féerie was a French theatrical genre and, as a ‘fairy play’ combined music, dance, mime, and acrobatics, in a fantasy plot set off by spectacular scenery and stage effects. Some critics noted that the visuals, with the transformational scene changes usually happening on the open stage, were more important than the words or music. The stories mainly came from the French fairy tale tradition, such as the stories by Charles Perrault. There were usually 4 main characters: the young lovers, the rival for the ingenue’s affection, and the lazy valet who focused on food. The story has supernatural forces that drive the lovers apart and the ending brings them back together, often with dazzling effect.

We found two stage images from an 1848 grande féerie, based on the story of the hen with the golden eggs. La poule aux oeufs d’or was in 3 acts and 28 tableaux. It had its debut at the Cirque National in Paris on 29 November 1848. It was staged again at the Théâtre de la Gaité in December 1872 with new music by Paul Henrion, and again in 1884 at the Théâtre du Châtelet in 1884, this time with new music by Albert Vizentini. We should say at the outset that this actual féerie had little to do with the fairy tale as we usually know it!

One writer in 2020 had this to say about the scenario: ‘I started reading the scenario but gave up after two pages. It was enough to realise that the play was rocambolesque: an absurd mix of ridiculous adventures, burlesque characters and the obligatory ingenue’.

People queuing at the opening of La Poule aux oeufs d’or at the Theatre National in Paris

The French writer and critic Théophile Gautier had this to say about féerie plays in general: ‘The characters, brilliantly clothed, wander through a perpetually changing series of tableaux, panic-stricken, stunned, running after each other, searching to reclaim the action which goes who knows where; but what does it matter! This dazzling feast for the eyes is enough to make for an agreeable evening’. You’ll notice that there’s not much there about the quality of the text or even of the music – it’s all about the visual spectacle!

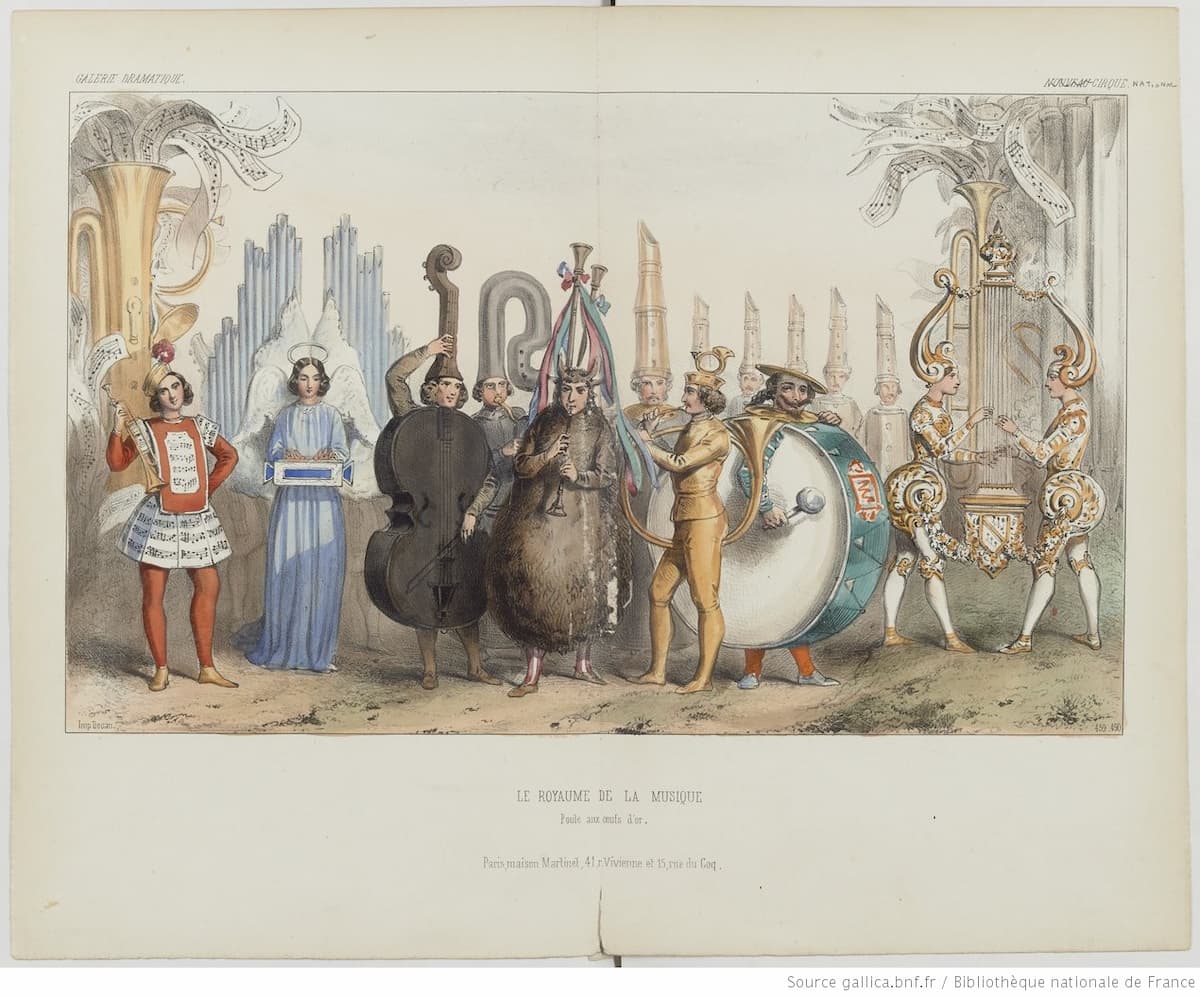

To get an idea of what kind of visual feast might be expected, we can look at two scenes from La poule aux oeufs d’or. These were illustrated in colour in the book Galerie dramatique, which shows the costumes used on stage in the Paris theatres. In 1,000 images, the book captured stage costumes for productions between 1844 and 1871, including our not-so-little hen.

An Angel (you’ll see her below) and Satan are the movers of the magic in the story. Our characters carry a totem (in this case the golden egg) that sparks the transformations of people, things, and places through the production. Some sample transformations included a cottage that would transform magically into a palace, all in the audience’s sight. In another scene, windmills turned into gondolas while a lake emerged in the middle of the stage. The more unbelievable, the better!

The actor Ameline appeared in the role of Satan, wearing a wonderfully evil costume with a pitchfork at the ready. The cat face on her costume is matched by the cat heads on the shoulders with their ear-like epaulets. The cat-heads on her knees and her boots, on her girdle, are all part of the perfect cat ‘look’. Somehow, the fearsome horns are somewhat mediated by the vase of flowers between them!

Ameline as Satan in La Poule aux oeufs d’or, Galerie dramatique, p. 436, 1848 (Gallica, ark:/12148/btv1b10541412f)

Next, we have the Empire of Animals who are appearing before the King and Queen. These are wonderful animal heads and then, just as in real life, the clothes tell you about the characters’ place in life – a cleric in black or a servant with a white apron? A dashing courtier with a lace collar or someone with more workaday clothing?

L’Empire des Animax in La Poule aux oeufs d’or, Galerie dramatique, p. 461–462, 1848 (Gallica, ark:/12148/btv1b10541455f)

The separate animal costume drawings, done by E. Bourdillat, show us the Bull, the Camel, and the Shark.

Bourdillat: Bull (Gallica, ark:/12148/btv1b6406085m)

Bourdillat: Camel (Gallica, ark:/12148/btv1b6406085m)

Bourdillat: Shark (Gallica, ark:/12148/btv1b6406085m)

However, the image that was the most striking to us was the scene depicting The Kingdom of Music. From the left to the right, we have a trumpet, and behind it stands an ophicleide spewing sheets of music. Next is the Angel, our other agent of change with Satan, carrying a portative organ, with extra pipes behind matching her wings. In the shadows behind her, there seem to be guitars with feet. A double bass is both an instrument and player, shown standing next to an inverted serpent. In the middle, decorated with red and blue ribbons is a very large and hairy bagpipe, playing the instrument’s chanter. A clarinet is tucked in behind the bass drum and a golden horn player is at the front. The bass drum, with red socks, is also an instrument and player, wearing cymbals as hat and ruff. More clarinets are lined up behind. At the far right is a most elegant harp.

Le royaume de la musique in La Poule aux oeufs d’or, Galerie dramatique, p. 459–460, 1848 (Gallica, ark:/12148/btv1b105414540)

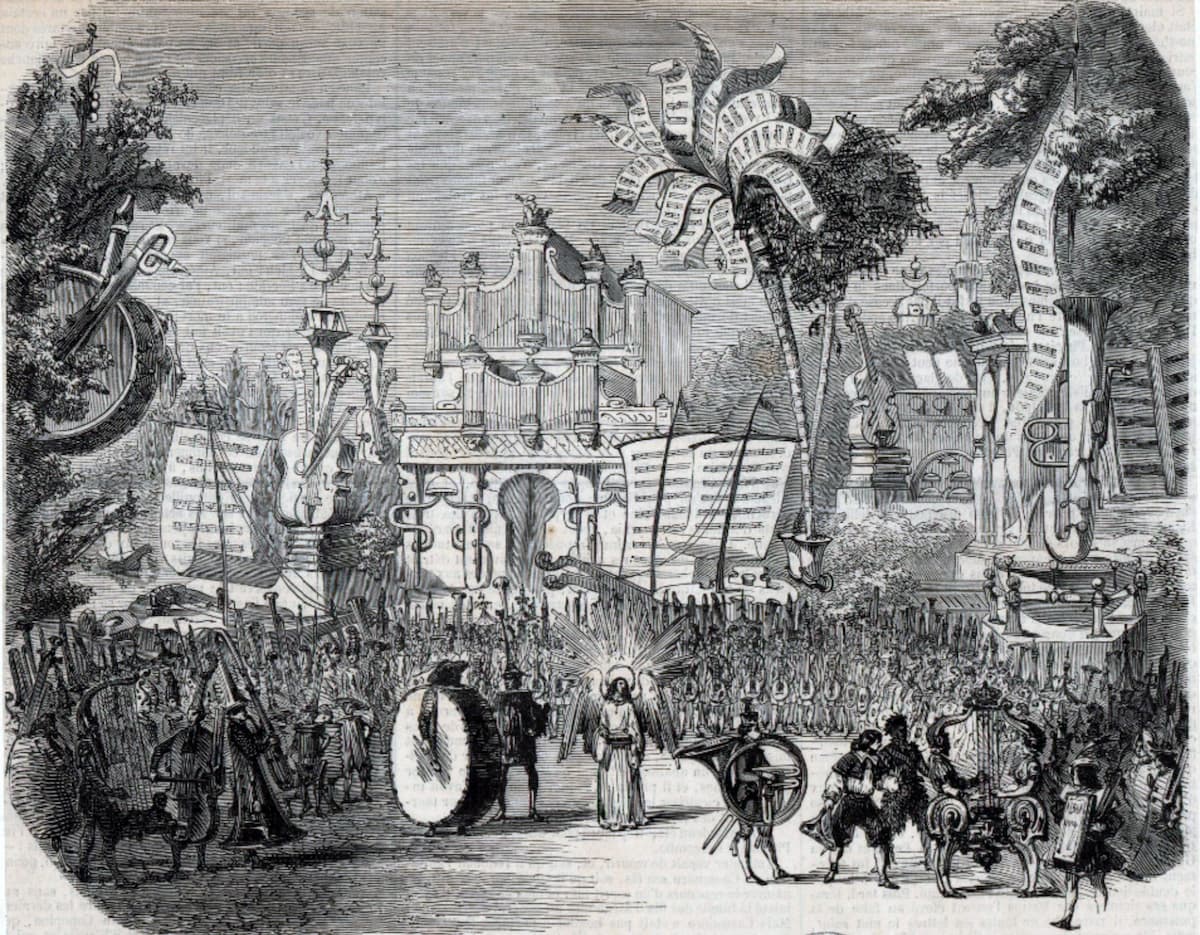

The féerie closes on the Island of Harmony, where all of our musical characters appear, with the organ-angel in the middle, bringing the story to a close.

The grand finale: stage setting for the 21th scene, L’Île de l’Harmonie

The Hen lived on stage for many more years, keeping the fabulous sets but changing the music. The composers Paul Henrion and later Albert Vizentini wrote music for other productions later in the 19th century.

Unfortunately, none of the music from this féerie has been recorded, but we can listen to music that the second composer, Albert Vizentini, was associated with.

Vizentini was a French violinist, composer, conductor, and writer of music. He succeeded Offenbach at the Théâtre de la Gaîté-Lyrique in 1875 where he was both music director and administrator. His grand shows included one of Offenbach’s féerie operas, Le voyage dans la lune.

Jacques Offenbach: Le voyage dans la lune – Act I: Ouverture (Orchestre National Montpellier Occitanie; Pierre Dumoussaud, cond.)

Féerie was simplified down by the end of the 19th century to become productions for children and then made the leap to film. In this short silent-film version of La poule aux oeufs d’or, directed by Gaston Velle in 1905, the story has been simplified back to its roots in fairy tales, but the same transformative stage effects, usually achieved through stop motion, are still part of the style. Watch, for example, the appearance of the ballet chickens at 03:40.

The Hen that Laid the Golden Eggs (1905)

We can’t find a record of who wrote the music for the first production and little of Henrion’s and Vizentini’s music has been recorded. However, in this Offenbach track, we can hear the humour, lightness, and velocity of French theatre music in the 19th century. We think that these were somehow the equivalent of today’s action movies – quick changes and always rushing!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter