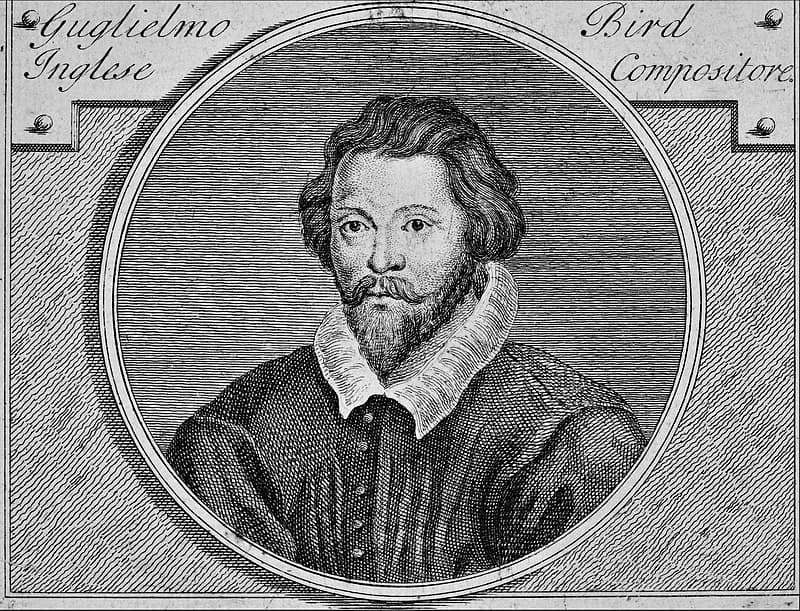

“Father of Musick”

400 years ago, on 4 July 1623, William Byrd (1540-1623) died at Stondon Massey, a small village near Chipping Ongar in Essex. According to his will, he was buried in the parish churchyard, but his grave has not yet been located. Byrd enjoyed the highest reputation among English musicians, and contemporary accounts hail him as a “Father of Musick,” and “Brittanicae Musicae Parens.” His music was copied extensively, and a number of poems ranked Byrd as among the greatest composers of the Renaissance. An Elizabethan scribe by the name of Baldwin mused:

William Byrd

Yet let not straingers bragg, nor they these soe commende,

For they may now geve place and sett themselves behynde,

An Englishman, by name, William BIRDE for his skill

Which I shoulde heve sett first, for soe it was my will,

Whose greater skill and knowledge dothe excelle all at this time

And far to strange countries abrode his skill dothe shyne…

William Byrd: “Ave verum corpus”

Byrd was born in London, but as no record of his birth has survived, the exact year is not known with certainty. Scholars, however, do agree that he was most likely born in 1539 or 1540. Byrd came from a wealthy family of merchants and musicians, and like his two brothers, he probably was a chorister. It seems likely that he was brought up in the Chapel Royal. This establishment in the royal household served the spiritual needs of the sovereign and the royal family and consisted of a number of priests and singers that travelled with the monarch. It has been assumed that Byrd was the student of the famed organist at the Chapel Royal, Thomas Tallis, and that the young student crafted several compositions in his teens.

William Byrd: Fantasia in C

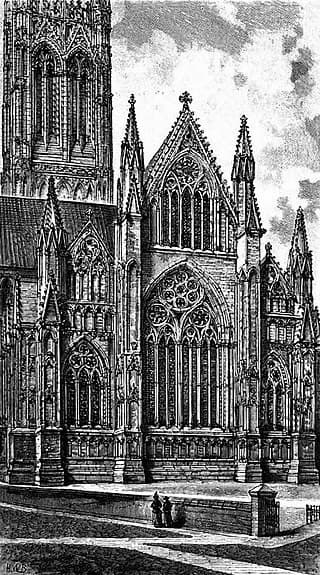

On 25 March 1563, Byrd was appointed organist and master of the choristers at Lincoln Cathedral, and having secured a large salary, he married Juliana Birley from Lincolnshire. He did get into hot waters with church authorities over his protracted organ playing during the services, and scholars interpret this “as the first indication of the stubborn Catholicism that would become a defining feature of Byrd’s life and works.”

Exterior View of the East End of Lincoln,

Development & Character of Gothic Architecture (1890)

In Lincoln, Byrd quickly developed his compositional skills, and wrote organ and virginal music, alongside settings of English poems as five-part consort songs for solo voice and viols. In addition, “most of Byrd’s English liturgical music seems to have been written at Lincoln, and some of his Latin motets published in 1575 appear to have been composed around this time as well.

William Byrd: Deus venerunt gentes (The Sixteen; Harry Christophers, cond.)

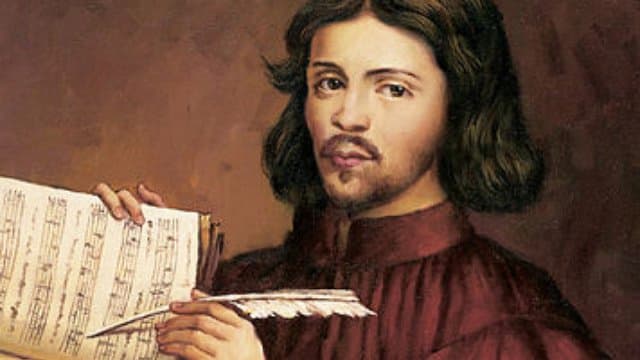

Thomas Tallis

In 1572, Byrd was appointed a “Gentleman of the Chapel Royal,” and shared organist duties with his teacher Thomas Tallis. Byrd quickly made the acquaintance of powerful Elizabethan lords, and he apparently “moved easily among the aristocracy.” He also gained favours with Queen Elizabeth I, a music lover and keyboard player. The Queen was a moderate Protestant, who shunned the extreme forms of Puritanism, and in 1575, she granted Thomas Tallis and William Byrd a 21-year monopoly for music printing and for lined music paper. This monopoly covered, “set song or songs in parts, composed in English, Latin, French, Italian, or other tongues as long as they served for music in the Church or chamber.” Tallis and Byrd immediately took advantage of the patent and produced a collection of 34 Latin motets dedicated to the Queen herself.

William Byrd: Laudate pueri Dominum

Byrd lived in an age of conflict between Catholics and Protestants in England. And Byrd’s loyalties were rather severely divided between the two religions. He and his wife were devout Catholics, yet at the same time, he held positions in Anglican churches and wrote music for their services. Most of his patrons were fellow Catholics, but the Earl of Northumberland was executed, and Lord Thomas Paget had to flee England in the aftermath of a supposed pro-Catholic plot against Queen Elizabeth I. As anti-Catholic sentiment was on the rise in England, Byrd and his family were frequently cited as “recusants.” This simply means that they were absent from services in the Church of England, which could lead to imprisonment and rather hefty fines. However, Byrd was considered loyal to the crown, and as we have seen, the Queen held him in high esteem.

William Byrd: Mass a 5 (King’s College Choir, Cambridge; David Willcocks, cond.)

William Byrd and Queen Elizabeth I

During the 1570s, Byrd started to compose a series of pavans and galliards for keyboard, and he became increasingly involved with Catholicism. In fact, Byrd got into serious trouble in 1583 for his indirect involvement in the Trockmorton Plot. Led by the English Roman Catholic Sir Francis Trockmorton, the plot consisted of a series of attempts to depose Elizabeth I of England and replace her with the jailed Mary, Queen of Scots. The objective was to encourage a Spanish invasion of England, assassinate Elizabeth, and put Mary on the English throne. Trockmorton was arrested and executed, and one of Byrd’s biggest patrons accused of sending money to Catholic abroad. “Byrd’s membership of the Chapel Royal was apparently suspended for a time, restrictions were placed on his movements, and his house was placed on the search list.”

William Byrd: Firste Galliard

Semi-retiring from the Chapel Royal in 1594, Byrd moved to a large property in Stondon Massey. Very few documents from this period of Byrd’s life exist, save for a large stash of legal papers as the ownership of Stondon Place was contested for well over a decade and a half.

Stondon Massey church

In terms of music, his attitude towards Latin sacred music underwent a significant change, and he now sought to provide music specifically for Catholic services. Some of this music must have sounded in the two local manor houses of Byrd’s patron Petre. He was a wealthy landowner and discreet Catholic, who held clandestine Mass celebrations throughout the year. However, Byrd’s devotion to Catholicism did not prevent him from contributing to the repertory of Anglican Church music, and in later years he also added a fair number of consort songs.

William Byrd: Browning for 5 Viols

In 1588, and again in 1589, Byrd published two collections of English songs. The publications contain the first madrigals ever published in England. As a scholar writes, “Byrd’s sets contain compositions in a wide variety of musical style, reflecting the variegated character of the texts which he was setting.” In his keyboard works, Byrd once again turned to pavans and galliards, “with keyboard figuration becoming more flexible in his later years.”

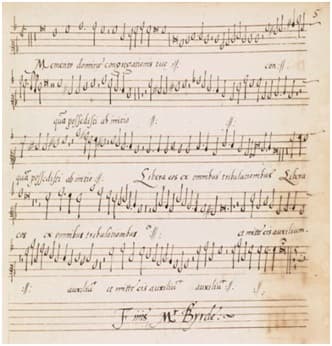

William Byrd’s motet

His last printed works were four quiet sacred songs of 1614. William Byrd died of heart failure on 4 July 1623. As a scholar writes, “Byrd belonged to the pioneer generation that built Elizabethan culture, and in music, he did it all by himself.” Among his 470 compositions, we find works in nearly all the genres of his time, including keyboard and other instrumental works, sacred music, and secular songs.

William Byrd: Lullaby, my sweet little baby (Michael Chance, counter-tenor; Christopher Wilson, lute; Fretwork)

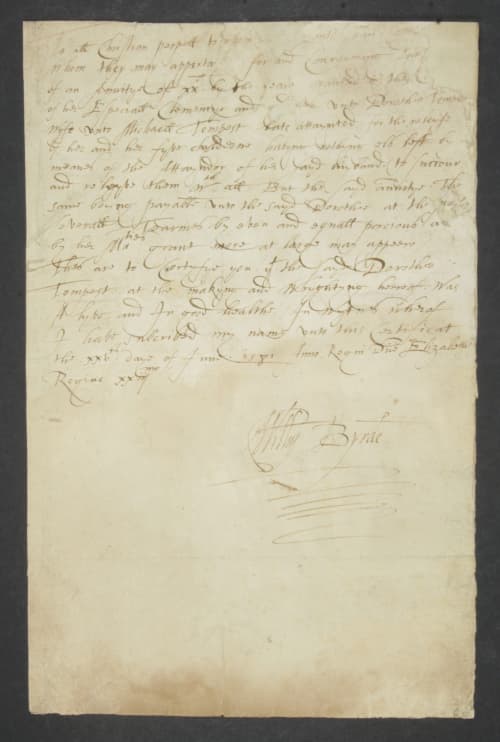

William Byrd’s autograph letter

Byrd, without doubt, was one of the great masters of European Renaissance music. “Perhaps his most impressive achievement as a composer was his ability to transform so many of the main musical forms of his day and stamp them with his own identity.” And while his musical mind is hard to characterize, his works disclose a highly personal synthesis of English and continental models. In addition, he virtually created the Tudor consort and keyboard fantasia, “and raised consort song, the church anthem and the Anglican service setting to new heights.”

William Byrd’s Mass for three voices

As a musicologist explained, “Byrd was always doing something unexpected, and he is probably to be regarded as one of the more intellectual of composers, and yet he also had a magic touch with sonority. Line, motif, counterpoint, harmony, texture, and figuration are all brought into play, and they are brought not singly but in ever-new combinations. Form was expression for Byrd, and the extraordinary variety of effect that he obtained in his pieces stemmed from his fertile instinct for shape and for musical construction.” After Byrd’s death, it was his Anglican music that survived, with the modern revival of his entire oeuvre having to wait until the first quarter of the 20th century.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter