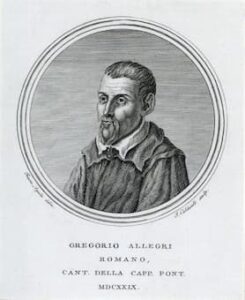

Caldwell: Gregorio Allegri (ca, 1740)

Gregorio Allegri (c. 1582-1652) was a composer and singer at the Vatican. He started his career in Rome as a chorister in the French national church, San Luigi dei Francesi. His skills as a composer in the cathedral of Fremo brought him to the attention of Pope Urban VIII who had him appointed as a contralto in the Sistine Choir at the Vatican in December 1629, a position he held for the next 23 years.

Allegri’s most famous work is Miserere mei, Deus, a setting of Vulgate Psalm 50 (= Psalm 51). Performed during the Tenebrae services of Holy Week, it was written for 2 choirs, one with five singers and the other with four. One choir sings a harmonization of the plainchant for the day, and the other choir (considered the solo choir) adds elaborations and cadenzas to the plainchant harmonization. The end result is 9-part polyphony, where each singer of each choir has their own part.

The young Wolfgang Mozart (1770)

The work was the property of the Sistine Chapel and it was forbidden to transcribe the music. It could only be performed during Holy Week and only in the Sistine Chapel. There were only three known copies of the music that left the Vatican, two of them to important kings: Leopold I, the Holy Roman Emperor, and the other to King John V of Portugal.

The young Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart heard it on a visit to Rome when he was 14 and transcribed it from memory, returning for a second hearing to check his work. He was rewarded by the Pope for his skills.

King’s College Choir (1963)

However, the work was more than the notes that Allegri wrote. The performance traditions of the Sistine Chapel Choir meant adding ornamentation to the basic work that weren’t written. The copies given to the two kings mentioned above didn’t preserve this unwritten tradition and it wasn’t until 1840, when Roman priest Pietro Alfieri published an addition with the ornamentation that it became known outside the Vatican. Alfieri’s intent was to preserve the Sistine Choir’s practices for the future and we all benefit from it.

One of the first modern recordings was done in 1963 by the King’s College Choir, under the direction of David Willcocks. With boy treble Roy Goodman singing the ultra-high notes, the recording captured the world’s attention and was the start of a whole series of Miserere recordings.

Gregorio Allegri: Il salmo Miserere mei Deus (Roy Goodman, treble; King’s College Choir, Cambridge; David Willcocks, cond.)

The original King’s College Choir production has inspired a number of more historically informed recordings, such as this 2006 one by Tenebrae.

Gregorio Allegri: Miserere (Tenebrae; Nigel Short, cond.)

Tenebrae with Nigel Short conducting

However.

What if this isn’t all that is seems to be?

It turns out that there was a mistake in the 1800s and that wonderfully aethereal high C was never in the original Vatican music. A transcription error changed the pitch of the solo choir up a fourth. The resulting key change, from G minor to C minor, is absolutely out of character for the time. Scribal error, as we’ll see, resulted in some unforgettable music.

ORA Singers, directed by Suzi Digby

A 2016 recording by the group ORA, under the direction of Suzi Digby, gives us 3 versions of the work in one track:

First: Allegri’s original unornamented work for the first part of the performance.

Second: Allegri’s work with the regular Sistine Chapel ornaments.

Third: Allegri’s work with the 19th century error transposition that created the aethereal high C.

Gregorio Allegri: Il salmo Miserere mei Deus (arr. B. Byram-Wigfield for choir) (Emma Walshe, Elizabeth Drury, sopranos; David Clegg, countertenor; William Gaunt, bass; ORA Singers; Suzi Digby cond.)

The note may not be there in the original, but it’s those high notes that caught everyone’s attention in the 20th century. Perhaps the Vatican officials were right in not permitting the original music to leave their hands – it’s only gotten messed up!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter