Herodias and Salome

Credit: Michael Cooper

Richard Strauss: Feuersnot, “Love Scene”

Feuersnot

Credit: palermo.repubblica.it

Richard Strauss: Taillefer, Op. 52 (1903)

Taillefer quickly disappeared from the repertoire, but the Symphonia Domestica composed around the same time, has proven far more resilient. This blatantly realistic autobiographical depiction of a twenty-four hour life cycle in the Strauss family includes the screaming child Franz, fights with his wife Pauline, and a graphically explicit “love scene” between the composer and his wife. Critics were quick to label “this composition as one of the most audacious challenges Strauss had hurled against good taste and common sense.” But they also criticized a transparent but nevertheless exceedingly heavy orchestration calling for approximately 110 players, including eight horns and five saxophones. The conductor Hans Richter famously suggested, “not all the gods burning in Walhalla could make one quarter of the noise of a single Bavarian baby in his bath.”

Richard Strauss: Symphonia Domestica, “Adagio”

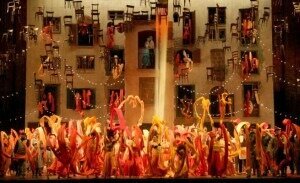

Concordant with his work on Taillefer and the Symphonia Domestica Strauss was busy composing a work that would establish him as the leading German opera composer of his time. Salome, based on a play by Oscar Wilde, gave rise to a modernist voice for the stage, one that resonated throughout a Europe preoccupied with the image of the sensual femme fatale. Erotic, murderous and biblical themes combine to reach a climax in Salome’s declaration of love and kiss for the severed head of John the Baptist. Paired with a colorful musical language, including extended tonality, chromaticisms, unusual modulations and tonal ambiguities, Salome greatly enlarged the artistic horizons of the theatrical and musical stage. Censors in London banned the opera until 1907, and Vienna had to wait until 1918 to hear a performance. As such, the Austrian premiere took place at the Graz Opera in 1906, with Arnold Schoenberg, Giacomo Puccini, Alban Berg and Gustav Mahler in the audience.

Richard Strauss: Salome

Scene 4: Ah! Du wolltest mich nicht deinen Mund kussen lassen, Jochanaan! (Salome)

Scene 4: Sie ist ein Ungeheuer, deine Tochter (Herod, Herodias)

Scene 4: Ah! Ich habe deinen Mund gekusst, Jochanaan (Salome)