Metronome

Credit: http://takelessons.com/

For Beethoven, who had exacting ideas about tempo, the metronome was what he needed to convey his compositional decisions. In fact, in a letter written in 1817, Beethoven declared “So far as I am myself concerned, I have long purposed giving up those inconsistent terms allegro, andante, adagio, and presto; and Maelzel’s metronome furnishes us with the best opportunity of doing so. I here pledge myself no longer to make use of them in any of my new compositions.” And when we look at the score for the Hammerklavier Sonata, written in 1818, we start with this annotation: “Maelzel’s Metronom [half note] = 138.” It may be, then, the publisher who added “Allegro” for those people who didn’t own a metronome. Since an Allegro can vary between 120 and 168 beats per minute, we can see immediately what appealed to Beethoven in being able to say exactly what he needed.

Over time, Beethoven’s metronome markings were largely disregarded. For many people, they just felt “too fast” and various conditions were blamed: perhaps Beethoven’s own metronome was defective or perhaps his increasing deafness was the problem. In many editions after the death of Beethoven, the metronome markings were actually omitted. Starting in the late 20th century, however, the markings were re-examined and tradition was thrown out the window. Accordingly, new ideas about the speed of Beethoven resulted, often making his music sound newly innovative and daring to our old tired ears.

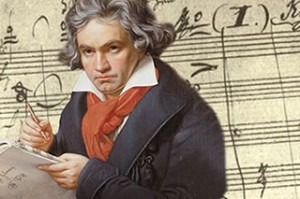

Beethoven

Credit: http://assets.cobaltnitra.com/

Check your own ears. The first two recordings here are Norrington’s newly researched performances and the third one is an in-hall recording from 1987 by the celebrated conductor Sergiu Celibidache.

Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 in E-Flat Major, Op. 55, “Eroica” IV. Finale: Allegro molto (London Classical Players; Roger Norrington, cond.)

Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 in E-Flat Major, Op. 55, “Eroica” IV. Finale: Allegro molto (Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra, Roger Norrington, cond.)

Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 in E-Flat Major, Op. 55, “Eroica” IV. Finale: Allegro molto (Munich Philharmonic Orchestra, Sergiu Celibidach, cond.)

I’ve always loved the (controversal) Norrington recordings. Once you get used to them, the majority of performances seem to lack a little in the way of Gusto.

I do understand his critics a little though. His rendition of the 9th gets insanely quick compared to other performances in the finale – with the shorter of his performances clocking in at 22:52 compared to Bernstein’s 28:57. If it’s not the way you’re used to hearing it, it’s almost absurd.

It raises the fascinating issue then of how later interpretations have essentially changed the classical canon over time – influenced by contemporary opinion, rather than what the Composer intended. If more historically informed performances leads to recordings as good as the Norrington recordings of Beethoven with the London Classical Players – I’m all for it!