Throughout the turbulent and highly emotional times of courtship and early marriage, Max and Elsa Reger could steadfastly rely on the support of Auguste von Bagenski, Reger’s mother in law. Auguste had taken an immediate liking to Max, and even urged her daughter to accept Max’s marriage proposal. At the same time, she was highly supportive of her daughter, who had just gone through an acrimonious divorce from her gambling husband. Auguste not only supported the marriage decision, she actually moved in with the newlyweds. If you were thinking that a threesome of that particular constellation would lead to severe frictions in the household and the marriage, you would be entirely wrong. Auguste became the emotional center of the family, and an undying cheerleader for the young and somewhat fragile composer. And Reger responded with a flood of works, including the Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Bach, Op. 81, the Sinfonietta Op. 90, and a collection of “Simple Tunes” (Schlichte Weisen), which by the time of completion in 1912 comprised roughly 60 Lieder. In addition, his career had blossomed and he accepted a professorship at the Munich Academy of Music, teaching composition and organ. By all accounts, Max and Elsa’s marriage was deliriously happy until 1904, the year Auguste passed away.

Throughout the turbulent and highly emotional times of courtship and early marriage, Max and Elsa Reger could steadfastly rely on the support of Auguste von Bagenski, Reger’s mother in law. Auguste had taken an immediate liking to Max, and even urged her daughter to accept Max’s marriage proposal. At the same time, she was highly supportive of her daughter, who had just gone through an acrimonious divorce from her gambling husband. Auguste not only supported the marriage decision, she actually moved in with the newlyweds. If you were thinking that a threesome of that particular constellation would lead to severe frictions in the household and the marriage, you would be entirely wrong. Auguste became the emotional center of the family, and an undying cheerleader for the young and somewhat fragile composer. And Reger responded with a flood of works, including the Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Bach, Op. 81, the Sinfonietta Op. 90, and a collection of “Simple Tunes” (Schlichte Weisen), which by the time of completion in 1912 comprised roughly 60 Lieder. In addition, his career had blossomed and he accepted a professorship at the Munich Academy of Music, teaching composition and organ. By all accounts, Max and Elsa’s marriage was deliriously happy until 1904, the year Auguste passed away.

After Auguste’s death, Reger’s way of dealing with adversity—either real or imagined—was to take up the bottle. In fact, his struggle with alcoholism would become a constant companion for the rest of his life. Unable to deal with Munich’s entrenched conservatism, Max and Elsa moved to Leipzig. For Max, the city of J. S. Bach, whom he called “the Alpha and Omega of music,” provided a brief window of optimism, and a number of major works appeared in quick succession. Elsa, on the other hand, simply hated the city. Isolated from her friends and her comfortable and familiar surroundings, Elsa fell into a deep depression. It clearly did not help that the couple could not have children of their own. To alleviate this situation, they adopted Maria-Marta Heyer in 1907. Nicknamed Christa, the arrival of the child only temporarily lifted Elsa’s mood. Only a year later, the Regers adopted a second child, Selma Charlotte Meinig, named Lotti Reger. Tenuous mental state aside, Elsa also underwent a serious operation in 1908. An extended period of recovery was punctuated by depressive episodes and jealous suspicions that her husband had an affair with the vocal teacher Martha Ruben, who took care of Christa and the household during her absence.

Concordantly, Max’s career was once again under pressure, and the Leipzig press became increasingly hostile to his compositions. To escape his domestic and professional troubles, Reger went on extended concert tours that more often than not, descended into the world of binge drinking. With the marriage in serious trouble, Max relocated his family to Meiningen. Yet, the same general and troubling pattern soon emerged. A brief period of optimism was soon followed by times of deep crisis. And a renewed attempt to put the marriage back together again led to a move to the city of Jena. Yet, the relationship was once more rocked to its foundations by the realization that their youngest daughter Lotti was suffering from severe psychiatric problems. Max Reger always knew that he would die young, and after a dinner in Leipzig on 10 May 1916, the composer complained of severe stomach pains. He died that night of a heart attack at age 43! Elsa Reger dedicated the rest of her life to the memory of her late husband. Almost immediately, she established the “Max Reger Archive,” and published her autobiography My Life with and for Max Reger. She tirelessly collected his correspondence and prepared a number of publications of his work. By 1947, she had also established the “Max Reger Foundation,” and the “Max Reger Institute.” Her efforts on behalf of her husband were so pervasive that Karl Straube once remarked, “as long as she doesn’t demand to conduct his music, her efforts are greatly appreciated.”

Max Reger: Schlichte Weisen, Op. 76, No. 35, 32, 3, 13

Max Reger: Schlichte Weisen, Op. 76, No. 48, 51, 22

You May Also Like

- Max Reger

“In music, I owe everything to J.S. Bach” Already a skilled pianist and organist, young Max Reger (1873-1916) saw performances of Meistersinger and Parsifal during his first Bayreuth pilgrimage. -

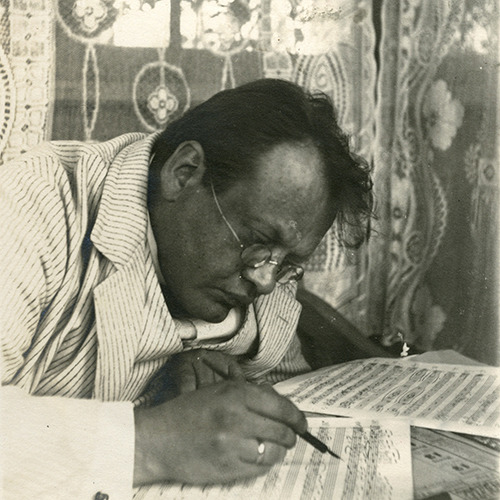

Max Reger 100 years ago, Max Reger (1873-1916), one of the giants of music in Germany passed away prematurely at age 43.

Max Reger 100 years ago, Max Reger (1873-1916), one of the giants of music in Germany passed away prematurely at age 43.

More Love

- Mathilde Schoenberg and Richard Gerstl

Muse and Femme Fatale Did the love affair between Richard Gerstl and Mathilde Schoenberg served as a catalyst for Schoenberg's atonality? - Louis Spohr and Marianne Pfeiffer

Magic for Violin and Piano How did pianist Marianne Pfeiffer inspire a series of chamber music? - Louis Spohr and Dorette Scheidler

Magic for Violin and Harp "Shall we thus play together for life?" - Zdeněk Fibich’s Erotic Diary: Moods, Impressions and Reminiscences A Musical Journey of Passion and Obsession