Pushkin’s Mozart and Salieri is a fantastic exploration of the nature of artistic creation. This short blank verse drama, written in 1830, has been re-told many times (notably by Rimsky-Korsakov in his 1898 opera of the same name and by Peter Shaffer in his 1979 play Amadeus and the 1984 film version, directed by Milos Forman). Despite the undisputable excellence of the more recent versions, the simplicity of Pushkin’s plot makes the point clear and elegantly.

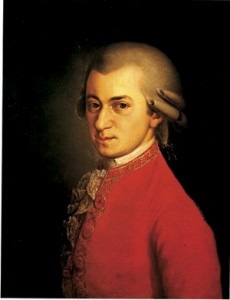

The legend of the rivalry between the two composers, culminating in the murder of Mozart by the jealous Salieri, is probably just that: there is widespread evidence that in reality Mozart and Salieri were, if not best friends, respectful and supportive of each other. Mozart and Salieri here, however, are simply Pushkin’s vehicles to discuss music – and art in general. In less than 20 minutes, with only the two characters (not counting the brief, and speechless, apparition of an old blind violinist), Pushkin masterfully explores two conceptions of art.

The legend of the rivalry between the two composers, culminating in the murder of Mozart by the jealous Salieri, is probably just that: there is widespread evidence that in reality Mozart and Salieri were, if not best friends, respectful and supportive of each other. Mozart and Salieri here, however, are simply Pushkin’s vehicles to discuss music – and art in general. In less than 20 minutes, with only the two characters (not counting the brief, and speechless, apparition of an old blind violinist), Pushkin masterfully explores two conceptions of art.

Writing from Salieri’s perspective, he opposes two ways of seeing art: craftsmanship and genius. On the one hand, Salieri sees music as a craft, fruit of painstaking learning and laborious development. Explaining his method, he says:

Craftsmanship

I took to be the pedestal of art:

I made myself a craftsman (…) dissecting

Music as if it were a corpse, I checked

My harmony by algebra.

Then he sees Mozart composing as if touched by the divine. Because of this disregard for art-as-craft, which endangers the very continuity of art, Salieri concludes that Mozart must die. And because he is the only one in their circle who can understand the supreme divinity of Mozart, he is the one who must kill him:

For I am the chosen, I must stop him now,

Or he will be the downfall of us all,

Us ministers and acolytes of music,

Not only me of humble fame… What good

If Mozart should live on to reach new heights?

Will music be the better? Not at all;

Music will fall again, he’ll leave no heir.

What use is he? He brings us, cherub-like,

Snatches of song from heaven, only to stir

Wingless desire in us poor sons of dust

And fly away… Then let him fly away!

Salieri is so in awe of Mozart’s genius, and so aware of his own limitations, that, in Shaffer’s play, he calls himself the patron saint of “all the world’s mediocrities”. But the crucial factor is that Salieri is not mediocre. He is a very accomplished composer, a creative musician and a gifted teacher. He is just not… genius? Sublime? Mozart? Perhaps his biggest impediment is in his head: Salieri sees art-as-craft as opposed to art-as-idea. The former requires toil and trouble, mathematical perfection and then, “having achieved a mastery of theory, [a] venture on the rapture of creation”: the idea serves the technique. The latter has the rapturous spark first, which is then worked by the technique: the theory at the service of the idea.

This opposition between art-as-craft and as idea is one of the main themes in modern art. Was expressionism, for instance, not about putting to the idea first, subverting the creative order? Or Dada; the ultimate subversion, the “anti-art”? Of course, the development of art-as-idea is inherently accompanied by subjectivism and meta-analysis, typified by “conceptual art”. Sometimes this can be developed ad absurdum. But when these two concepts of art, creative genius and technical mastery, go hand-in-hand, we have Mozart.

…and Pushkin. It is so fitting that this whole story was first crystallised by him, who was, for the Russian language, as miraculous a creator as Mozart was for music. So, in Mozart and Salieri, we have not only an exploration of art, but also a double mirror, in which a perfect specimen of genius artist imagines what the craftsman artist would think of someone like him. We have, in short, three Mozarts: the actual one, the one imagined by Salieri in the play and Pushkin himself. This play then becomes a beautiful concerto.

…and Pushkin. It is so fitting that this whole story was first crystallised by him, who was, for the Russian language, as miraculous a creator as Mozart was for music. So, in Mozart and Salieri, we have not only an exploration of art, but also a double mirror, in which a perfect specimen of genius artist imagines what the craftsman artist would think of someone like him. We have, in short, three Mozarts: the actual one, the one imagined by Salieri in the play and Pushkin himself. This play then becomes a beautiful concerto.

Ps. Unfortunately, I cannot yet appreciate Pushkin in the original Russian, and am sure I am losing a lot in the translation. Antony Wood’s translation nevertheless transmits Pushkin’s ideas very effectively (published in Mozart and Salieri – The Little Tragedies, which includes Pushkin’s 1830 plays, mostly drawn from musical themes – including The Stone Guest, about Don Giovanni).

Photo credits: meetthecomposers.org, freemasonry.bcy.ca

More Arts

- Alexandre Dumas (1802-1870)

“Music is the only noise for which one is obliged to pay” We look at his collaborations with composers on operas and more! - “In the Hall of the Mountain King”

Henrik Ibsen in Music "Peer Gynt goes very slowly. It is a horribly intractable subject except for a few places… " - Edgar Degas (1834-1917)

“No art could be less spontaneous than mine” Look at Degas' burning passion for opera from his artwork - Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669)

Born on 15 July Learn about his ancestry, childhood and more