Frederic Rzewski

“The People United Will Never Be Defeated” (1975)

Stephen Drury, piano

J. S. Bach

Goldberg Variations BWV988 (1741)

Glenn Gould, piano (1955)

Beethoven

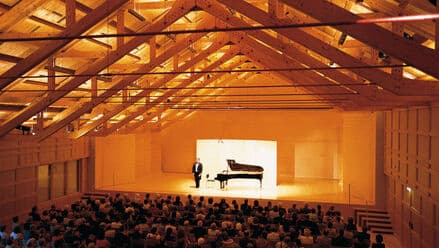

Early this summer I attended the opening concert of the Ludwigsburger Schlossfestspiele in Ludwigsburg, Germany, given by the talented young Russian-born German pianist, Igor Levit. The program consisted of Beethoven’s ‘Thirty-three Diabelli Variations in C-Major on a Waltz by Anton Diabelli’ and Frederic Rzewski’s ‘The People United’.

In music, variation on a theme has been used by many composers throughout the centuries — the most famous being Johann Sebastian Bach’s Goldberg Variations. Similarly, Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations and Rzewski’s variations on “The People United Will Never Be Defeated” are also considered masterpieces and are the subject of my article today.

In art, variations on a theme have also been common – such as Claude Monet’s Water Lilies, his many renditions of the Japanese Bridge in Giverny, Picasso’s Forty-eight Versions of Velázquez’, Las Meninas (which I will discuss today), as well as the many ‘series’ paintings by Motherwell, Rothko, and Diebenkorn’s Ocean Park Series, which is now on view at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C.

Beethoven was about fifty years old and almost entirely deaf when he worked on the Thirty-three Variations in C-major on a Waltz by Anton Diabelli between 1819 and 1823. At the same time, he was working on his other great masterpieces, “Missa solemnis” and his Ninth Symphony – large, dimensional works. Impetus for the variations came from a request by the Viennese editor, Anton Diabelli, who had composed a waltz, which he had sent to several famous composers, asking for a one piece variation. Beethoven proceeded to write thirty-three variations, not as small, individual pieces, following one another, but as a dynamic, interrelated piano composition. His variations, published in 1823 by Capelli and Diabelli, found little attention amongst his contemporaries and saw their first public performance by the pianist and conductor, Hans von Bűlow in the winter of 1857-58. However, Diabelli saw them as “a great and important masterpiece worthy to be ranked with the imperishable creations of the classics” entitled “to a place beside Johann Sebastian Bach’s famous masterpiece in the same form”, i.e. the Goldberg Variations.

Beethoven had completed about two-thirds of the variations in 1819, but then put them aside until 1823, completing them only in that year after having made a few changes. The Diabelli waltz, as a theme, appears in various disguises throughout the composition. There are many changes in texture, harmony and rhythm. In the beginning, it takes us from the form of a ‘march’ — almost to be considered as a parody of the waltz — to a march in the disguise of a ‘German dance’ (variation 25), to elements of the Baroque period – evocative of J.S. Bach, (var. 24, 29, 30 and 31). Variation 31, the great Largo, is a reference to the Goldberg Variations itself, not so much an imitation, but a homage not only to Bach ( just as is the triple fugue in variation 32), but to Händel as well. The following fugue (variation 33), a lively Minuet and coda are reminiscent of Mozart. The difficulty and complexity have made performances of the Diabelli variations rare, and it is only extraordinarily talented pianists, such as Igor Levit, who can do it justice.

Frederic Rzewski, born in 1938 in Massachusetts, left the United States in the 1970 for Europe. Rzweski was commissioned to write “The People United Will Never Be Defeated” which was supposed to accompany the Diabelli Variations in a concert. It saw its world premiere on February 1976, at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. played by Ursula Oppens, to whom Rzweski had dedicated the piece.

Rzewski’s political convictions influenced his work from the 1970’s onward, which becomes apparent in the variations of “The People United …”. The major theme of this composition is the Chilean battle hymn, “El pueblo unido, jamás será vencido”, which had become the symbol of resistance against the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. The 36 variations are divided into groups of six, with each group focusing on a different musical element — there are silences, lush chorale passages and virtuoso sections, where the pianist’s two hands play a rapid succession of chords in opposite directions from the center of the piano. The composer uses popular songs and many different musical styles (from Franz Liszt to John Cage), speaking to and involving the public. Included, we find the Italian folksong “Bandiera Rossa”, Bertolt Brecht’s and Hanns Eisler’s song “Voran, du Arbeitsvolk” (Onward, Workers), as well as blues elements. The pianist is also required to whistle and to beat on the piano — typical techniques of modern 20th century piano writing.

The topic of theme and variations in art becomes particularly pertinent in Picasso’s versions of Velázquez’ Las Meninas. I had discussed Velázquez’ painting in my recent article on The Golden Age in Spain: its elusive subject matter, the question of space and time and the relationship of the protagonists, who all had existed in ‘real’ historical time. In the ‘fictional’ time of the painted space they had become ‘painted’ subjects who seemed to exist only as such. The question of the ‘real’ subject of the painting is unanswered — its meaning and interpretation remain elusive.

Picasso, in his 48 versions, of which I have included several examples, uses the same subject matter as a theme and then proceeds to create his variations in manipulating space, showing some or all of the protagonists within the painted space. Elements of Velázquez’ painting are recognizable; small, insignificant parts are emphasized to create many new and different versions of the original painting. Picasso shows myriad possibilities of exploring different dimensions of space, of figures and objects in space, painting in black and white or color, always re-creating and creating new interpretations, involving the viewer — leaving the painting’s meaning open to interpretation, which just like music, remains ineffable.