From Flow My Tears to Lachrimae, or Seven Tears

The composer John Dowland (1563-1626) perfected the idea of the lute song. He also thought himself as suffering from melancholy, a known illness of his time. Melancholy was one of the four temperaments of the body, characterizing the 4 personality types: Sanguine, Choleric, Melancholic, and Phlegmatic. Moved into modern psychology, we now characterize these types slightly differently. Sanguine are now viewed as outgoing: highly talkative, active, and social. Choleric are also extroverts: independent and ambitious, decisive and goal oriented. Melancholic are introverts, detail-oriented and analytical. Phlegmatic are relaxed and peaceful, sympathetic while hiding their own emotions.

Albrecht Dürer: Melencholia I (1514)

It was Melancholy that Dowland claimed as his own and much of his musical output leads on that theme. Songs titles such as ‘Go Cristall Tears,’ ‘Flow my tears,’ ‘I saw my Lady weepe,’ and ‘In darkness let me dwell,’ give an indication of the darkness of his thoughts. However, Dowland, in and of himself, was not someone who moped around weeping all the time – there are many kinds of tears: tears shed for joy, happiness and relief as well as those that fall in true despair and sadness, as Dowland himself pointed out:

Many men are melancholy by hearing music, but it is a pleasing melancholy that it causeth; and therefore to such as are discontent, in woe, fear, sorrow, or dejected, it is a most present remedy: it expels cares, alters their grieved minds, and easeth in an instant.

Dowland was described by a contemporary as ‘a cheerful person… passing his days in lawful merriment’, and yet seems to have considered himself amongst the chiefs of the melancholics, taking pride in his ‘unhappy fortunes.’

Isaac Oliver: An Unknown Man, Aged 27 (thought to be John Downland), 1590 (Victoria and Albert Museum)

One of the most important works Dowland wrote was the instrumental Lachrimae Pavan, which was in circulation in England by the 1590s. It was rewritten with words in 1600 as Flow My Tears and published in Dowland’s Second Book of Songs. A pavan is a slow processional dance, popular in the 16th century; as a musical form, it was in use by composer through the Baroque period, when it was replaced by the allemande and courante, as in Bach. Because the dancers were on display and they would make a kind of wheel or tail before each other, like a peacock, the dance took the name pavan (peacock).

Title page of Lachrimæ, or Seven Teares Figured in Seven Passionate Pavans, 1604

In 1603, Dowland finished his book of consort music book called Lachrimæ, or Seven Teares Figured in Seven Passionate Pavans, which was published in London in 1604. The book is dedicated to Anne of Denmark, queen to James I of England, and sister to Dowland’s current employer, Christian IV of Denmark. While Dowland was in England in 1603, he sought and received an audience with Anne where it is thought he both asked her permission to dedicate the book to her and for consideration for a court post. He was successful in the first request and unsuccessful, for the third time, on the second request.

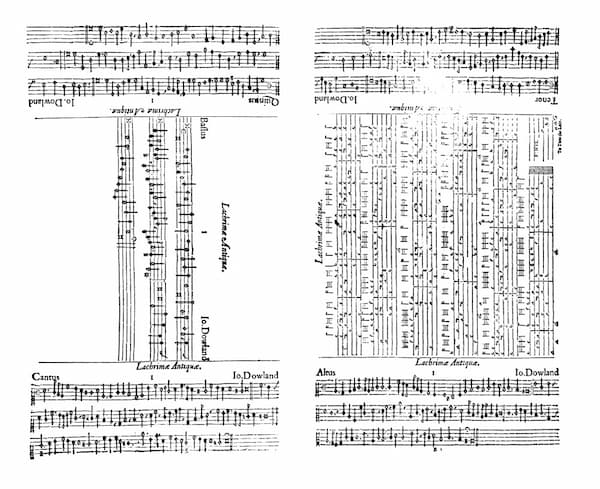

In Lachrimae, he took his song Flow My Tears and wrote it out as seven different pavans for performance by consort. Each pavan was designed to be a different kind of tear, just as he had detailed in the different kinds of melancholy. As he had in his First Books of Songs or Ayres, he laid the music out for playing around a table.

Lachrimae Antiquae Left & Right page

1. Lachrimae Antiquae

2. Lachrimae Antiquae Nouae

3. Lachrimae Gementes

4. Lachrimae Tristes

5. Lachrimae Coactae

6. Lachrimae Amantis

7. Lachrimae Vera

First, listen to the song, so you can understand what Dowland does in the pavans.

John Dowland: Flow my tears (Lachrime) (Rogers Covey-Crump, tenor; Jakob Lindberg, lute)

Flow, my tears, fall from your springs!

Exiled for ever, let me mourn;

Where night’s black bird her sad infamy sings,

There let me live forlorn.

Down vain lights, shine you no more!

No nights are dark enough for those

That in despair their last fortunes deplore.

Light doth but shame disclose.

Never may my woes be relieved,

Since pity is fled;

And tears and sighs and groans my weary days, my weary days

Of all joys have deprived.

From the highest spire of contentment

My fortune is thrown;

And fear and grief and pain for my deserts, for my deserts

Are my hopes, since hope is gone.

Hark! you shadows that in darkness dwell,

Learn to contemn light

Happy, happy they that in hell

Feel not the world’s despite.

We can read the darkness in the text: tears, exile, infamy, forlorn, dark, despair, shame, and so on. At the end, he concludes that even those in hell are happier than he. We don’t know what occasioned this flight of melancholy and tears, but the music has been important ever since he wrote it.

The first pavan in the Lachrimae collection, Lachrimae Antiquae, was the original from the 1590s.

John Dowland: Lachrimae, or Seven Tears – I. Lachrimae Antiquae (Dowland Consort)

The next work, ‘Lachrimae Antiquae Novae,’ was a new take on the work that had been circulating already for nearly a decade. It was probably thought of as a work to pair with the first ‘Lachrimae Antiquae.’

John Dowland: Lachrimae, or Seven Tears – II. Lachrimae Antiquae Nouae (Dowland Consort)

‘Lachrimae Gementes’ or ‘sighing or groaning tears’ takes its title from a sacred source, the Salve Regina prayer: ‘Ad te suspiramus, ge mentes et flentes in hac lacrimarum valle’ (To you, we send our sighs, groaning and weeping in this valley of tears). Since we know Dowland had been caught in the Catholic/Protestant problems of his age (he was born Protestant but converted to Catholicism while abroad) that were critical in keeping him out of the Catholic court post he sought, we can read this as indicative of his own realization of the role of religion in his life.

John Dowland: Lachrimae, or Seven Tears – III. Lachrimae Gementes (Dowland Consort)

The ‘Lachrimae Tristes’ or ‘sad tears,’ changes the falling notes of the original song to one that falls then rises. Dowland introduces some extreme key changes in this work (starting around 01:35) that can sometimes seem shocking.

John Dowland: Lachrimae, or Seven Tears – IV. Lachrimae Tristes (Dowland Consort)

The ‘forced, insincere tears’ of ‘Lachrimae Coctae’ also have the extreme key changes heard in the fourth piece, but they are not presented so strikingly. Dowland plays with the counterpoint in this piece, making it more complex and even setting the Cantus and Quintus voice in canon at the beginning.

John Dowland: Lachrimae, or Seven Tears – V. Lachrimae Coactae (Dowland Consort)

Dowland adds a walking bass to ‘Lachrimae Amantis’ or ‘lover’s tears.’ Although the initial feeling is that it’s more relaxed piece, the middle section breaks this up with a series of long suspensions and dissonances that ratchets the tension up again.

John Dowland: Lachrimae, or Seven Tears – VI. Lachrimae Amantis (Dowland Consort)

The last pavan, ‘Lachrimae Verae’ or ‘true tears,’ brings us to the final set of tears. These true tears are the final release from the previous pavans – he’s gone through new and old style, wept false tears, sad tears, tears for a lover, and comes to the point where he must find peace in his own true tears.

John Dowland: Lachrimae, or Seven Tears – VII. Lachrimae Verae (Dowland Consort)

The work is a remarkable tour-de-force of not only Dowland’s skill as a composer but also how he represents the different kinds of melancholy in music. Changing the melody, adding counterpoint, adding harmonic twists, all of this, in the end, must simply end in a sense of peace with the life one lives.

That Dowland identified with Melancholy can be seen in two details. He often signed himself ‘Jo: Dolande de Lachrimæ’ after his most famous creation, and the next piece in the Lachrimae collection had the punning title “Semper Dowland, semper dolens” (always Dowland, always doleful or always mournful.).

We’ll close with a return to the song, here arranged for voice and lute and modern instruments that help emphasize the sadness of it all.

John Dowland: Book of Songs, Book 2 – Flow my tears (arr. B. Guy and J. Potter for voice and chamber ensemble) (John Potter, tenor; John Suman, soprano sax, bass clarinet; Maya Homburger, baroque violin; Stephen Stubbs, lute; Barry Guy, double bass)

So, flow your tears. They’re all for the sadness in the world and the sadness in life, but, in the end, calm and resolution will prevail.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter