Opera in London in the 1790s was a cut-throat competition. Handel had abandoned Italian opera in 1741, and the quality began to fall. The high fees that singers such as the castrati Senesino and Farinelli and the soprano Cuzzoni commanded were not matched by income from the seats, which remained at half a guinea. Operas at the King’s Theatre in the Haymarket were given on Tuesdays and Saturdays, December to June, and comic opera and ballet gained importance. Management companies came and went (like the money).

The other principal houses, Covent Garden and Drury Lane, put on musical entertainment in English and made money. Lighter works such as Arne’s Artaserse and his pastiche Love in Village were popular, as was Linley’s The Duenna, setting the play by Sheridan. Italian operas were given in English, and the performing schedule was six days a week, and the price was half guinea.

R. B. Sheridan and Thomas Harris bought the King’s Theatre in 1778 for £22,000 (over half of which was a mortgage). Sheridan and Harris were the principal owner-managers of Covent Garden and Drury Lane and hoped to revive the 1662 theatre patent to run their third theatre. Galliani bought the mortgage, Sheridan bought out Harris, sold his shares to William Taylor, and then Taylor and Galliani began to fight for control of the theatre.

In 1782, Taylor had the King’s Theatre gutted and rebuilt with an immediate outcome of bankruptcy. Galliani took over management from 1785 to 1789. The theatre burned down in June 1789. Rebuilt, it opened in February 1791, but the Lord Chancellor refused to grant it permission to run.

Meanwhile, another theatre was coming into play: The Pantheon. Located on Oxford Street, it had been built in 1772 as an exhibition space and was altered in 1790 to be an opera house. Now London had two opera houses, and only one had a license for performances.

One ballet that was given its premiere at the Pantheon in 1791 was Hérold’s La fille mal gardée.

Ferdinand Hérold: La fille mal gardée (arr. J. Lanchbery) – Act I: Introduction (Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra; Barry Wordsworth, cond.)

The King’s Theatre hired dancers and Haydn. The Pantheon hired a strong company that included Mara and Pacchiarotti and tried to hire Mozart but wasn’t successful in that. The Pantheon was committed to opera seria but would also do opera buffa in their second company. The Pantheon gave 55 performances in the 1790—91 season, and the 4 performances into the next season mysteriously burned down. It didn’t survive but its demise solved the two-opera-house problem for London.

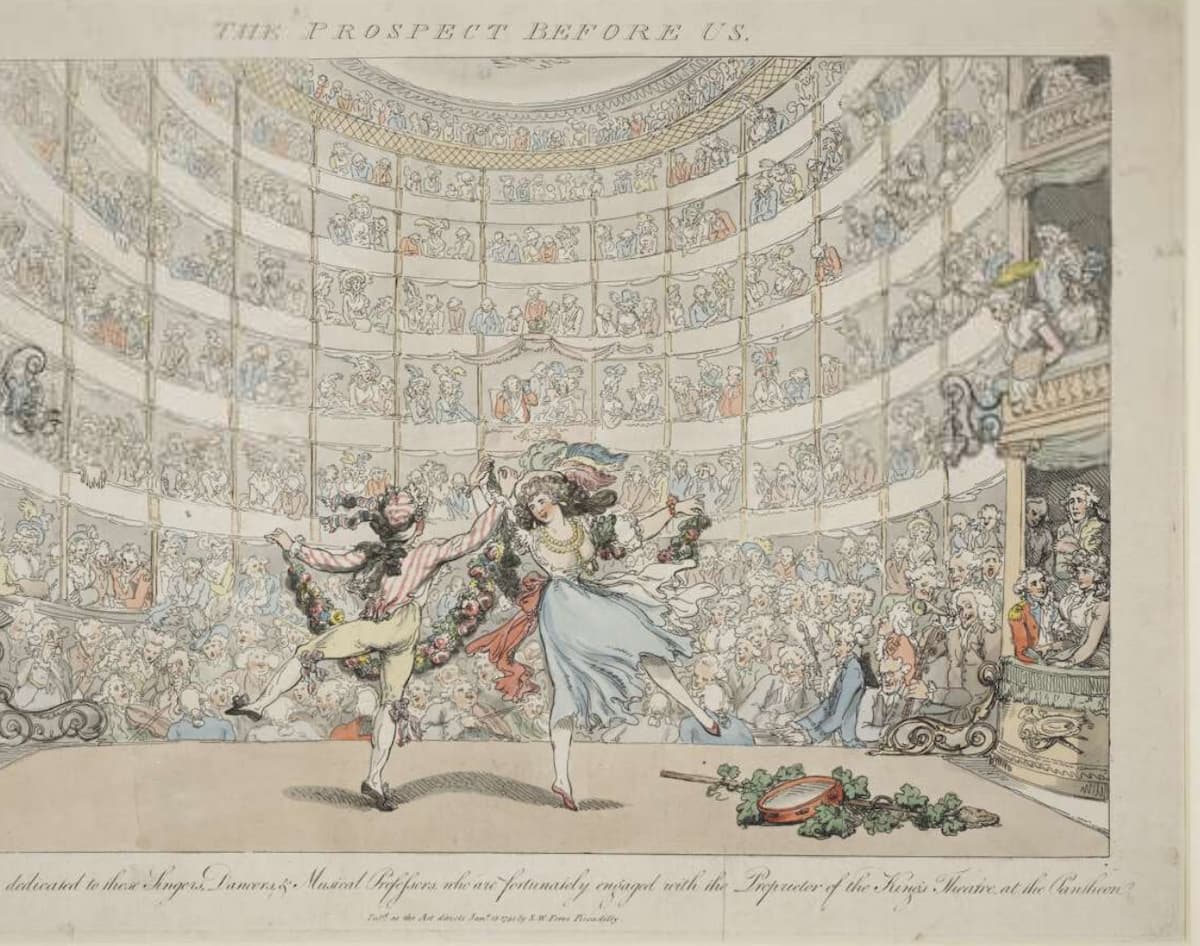

At the height of the competition, two prints came out in London from the hand of caricaturist Thomas Rowlandson. Both are dated 13 January 1791 and have the same title: The Prospect Before Us.

Thomas Rowlandson: The Prospect Before Us, 13 January 1791 (British Museum) – Opera House in the Haymarket

Set in the newly finished Pantheon, M. Didelot and Mme. Theodore dance in the ballet of Amphion and Thalia. Around them, all is happiness and light. The house is crowded, and there are three tiers of on-stage boxes filled with fans. The six tiers of the house shown here were actually four tiers. At the centre is the royal box, in which the King (looking through his opera glass) and the Queen can be seen. The caption at the bottom read: ‘Respectfully dedicated to those Singers, Dancers, & Musical Professors, who are fortunately engaged with the Proprietor of the King’s Theatre, at the Pantheon.’

The Royal Patronage for the Pantheon and its success is skilfully sent up by Rowlandson in his depiction of what was happening down the Haymarket. This scene is set out in front. The building front has a banner, ‘Pray Remember the Poor Dancers’ (in the style of begging sailors who carried a ship), and the front line is of ragged and begging performers. From the left, a cellist and a timpanist play while a violinist is clad only in a tattered shirt. The hornist lacks trousers. The dancer, probably Mlle Hillisburgh, is clad in finery above and rags below. The next dancer, in a wig and rags, holds out his cap for a coin from a chimney sweep. A female singer also in rags emotes dramatically – this may be the Italian singer Giovanna Sestini. The last beggar, an elderly man, receives a liver and lights from a passing butcher. The caption, a bit more vindictively reads: ‘Humanely inscrib’d to all those Professors of Music, and Dancing, whom the cap may fit.’

Thomas Rowlandson: The Prospect Before Us, 13 January 1791 (British Museum) – Pantheon, London

The two drawings were created as a pair and give us a startling insider’s view of the prosperity and poverty of the performing life of 1790s London.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter