I had long believed that the poems most frequently set to music came from the pen of Goethe, Schiller, Heine, Whitman, or Verlaine. In reality, however, that particular honour probably belongs to the American poet Emily Dickinson. In 1992 a literary scholar counted over 1,600 musical settings of her poems, a number that dramatically increased through the 1990s.

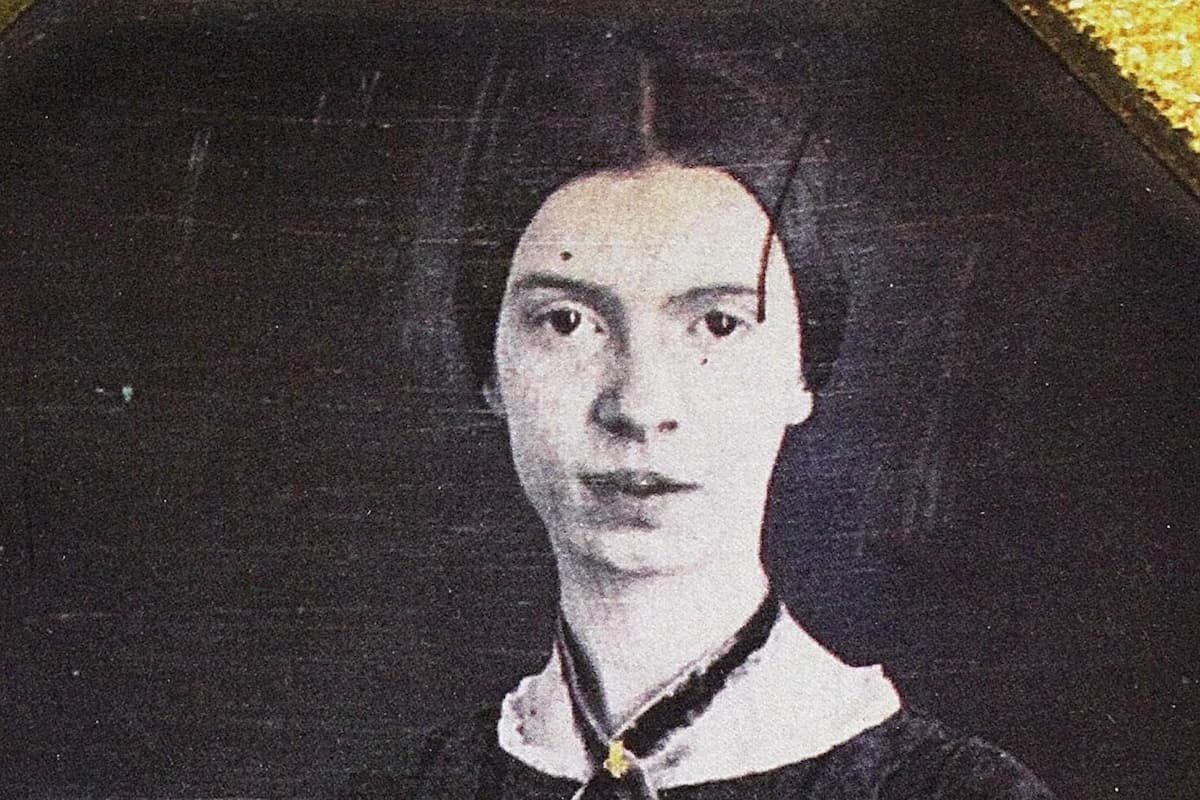

Emily Dickinson

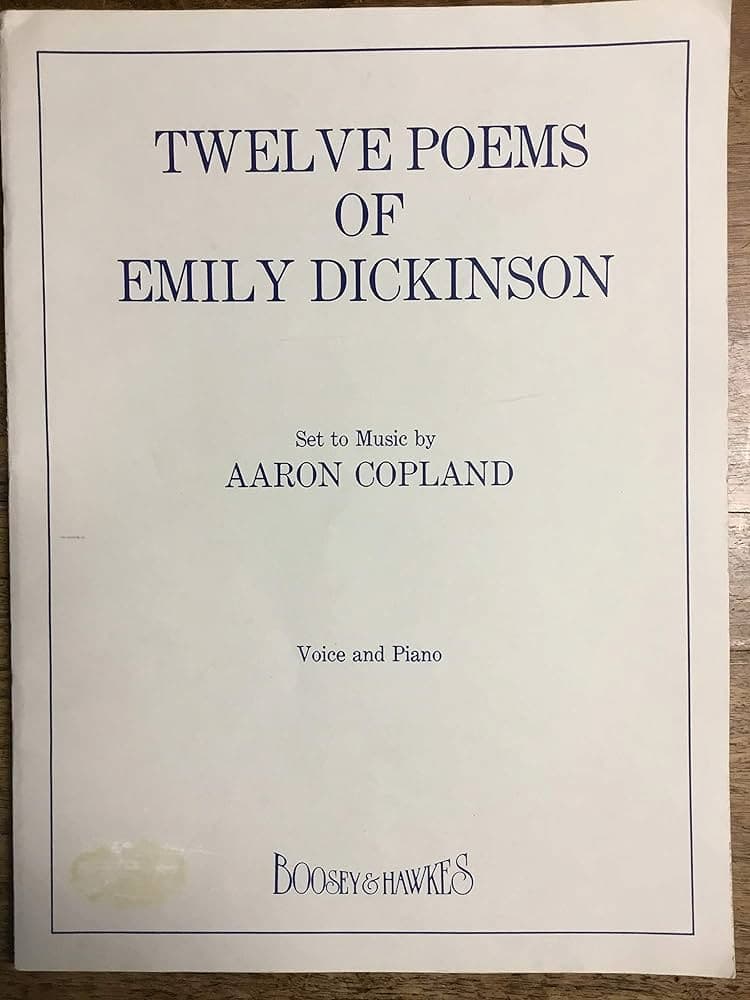

This is even more astonishing since only 10 of her over 1,800 poems were published during her lifetime. Little known during her life, Dickinson has become one of the most important and modern figures in American poetry. Her poems were unique for her era, frequently just a couple of epigrammatic lines “rising to a smallish clutch of verses.” Clearly, we won’t be able to feature all the extant musical settings, but decided to sample Aaron Copland’s 12 Poems of Emily Dickinson.

Aaron Copland: 12 Poems of Emily Dickinson, No. 1 “Nature, the gentlest mother” (Lynda Poston-Smith, soprano; Robert Carl Smith, piano)

Nature, the gentlest mother

Impatient of no child,

The feeblest or the waywardest, –

Her admonition mild

In forest and the hill

By traveller is heard,

Restraining rampant squirrel

Or too impetuous bird.

How fair her conversation,

A summer afternoon,

Her household, her assembly;

And when the sun goes down

Her voice among the aisles

Incites the timid prayer

Of the minutest cricket,

The most unworthy flower.

When all the children sleep

She turns as long away

As will suffice to light her lamps;

Then, bending from the sky,

With infinite affection

And infiniter care,

Her golden finger on her lip,

Wills silence everywhere.

Aaron Copland: 12 Poems of Emily Dickinson, No. 2 “There came a wind like a bugle” (Lynda Poston-Smith, soprano; Robert Carl Smith, piano)

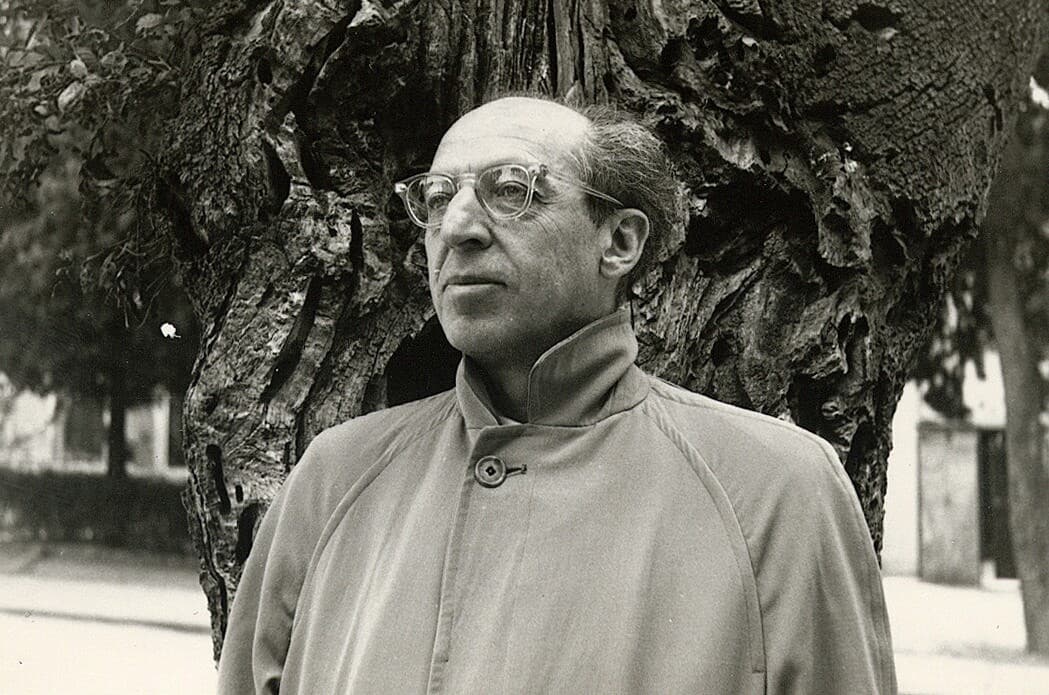

Aaron Copland

Dickinson was born on 10 December 1830 in Amherst, Massachusetts. Her father was a lawyer who eventually was elected to the Massachusetts State Legislature and served for a single term in the U.S. Congress. We know little of her mother, but the family certainly had strong ties with the community.

Dickinson studied for seven years at the Amherst Academy, and by her own account, “she delighted in all aspects of schooling, the curriculum, the teachers, the students.” She was particularly interested in the study of botany, and her early poems question the prying interest of the sciences. Apparently, she was much less compelled by conventional religious wisdom.

Aaron Copland: 12 Poems of Emily Dickinson, No. 3 “Why do they shut me out of Heaven?” (Lynda Poston-Smith, soprano; Robert Carl Smith, piano)

Why do they shut me out of Heaven?

Did I sing too loud?

But I can sing a little minor,

Timid as a bird.

Wouldn’t the angels try me

just once more

Just see if I troubled them

But don’t shut the door!

Oh if I were the Gentlemen

in the White Robes

and they were the little Hand that knocked

Could I forbid?

Why do they shut me out of Heaven?

Did I sing too loud?

Aaron Copland: 12 Poems of Emily Dickinson, No. 4 “The World feels dusty” (Lynda Poston-Smith, soprano; Robert Carl Smith, piano)

Aaron Copland’s 12 Poems of Emily Dickinson

Dickinson left the academy at the age of 15 and entered Mount Holyoke Female Seminary. According to an anecdote, the young women were divided into three categories. Those who were established Christians, those who expressed hope, and those who were “without hope.” Apparently, Dickinson was the only student in the last category.

Dickinson only stayed at Mount Holyoke for a single year, possibly realizing that the institution had little to offer. Returning to the family home in Amherst, Dickinson lived much of her life as a recluse and in isolation. She was considered an eccentric by locals and developed a reluctance to greet guests. Later in life, she even refused to leave her bedroom. The majority of her friendships were entirely based on correspondence, and she was never married.

Aaron Copland: 12 Poems of Emily Dickinson, No. 5 “Heart, we will forget him” (Lynda Poston-Smith, soprano; Robert Carl Smith, piano)

Heart, we will forget him

You and I, tonight.

You may forget the warmth he gave,

I will forget the light.

When you have done, pray tell me,

That I my thoughts may dim;

Haste! lest while you’re lagging,

I may remember him!

Aaron Copland: 12 Poems of Emily Dickinson, No. 6 “Dear March, come in!” (Lynda Poston-Smith, soprano; Robert Carl Smith, piano)

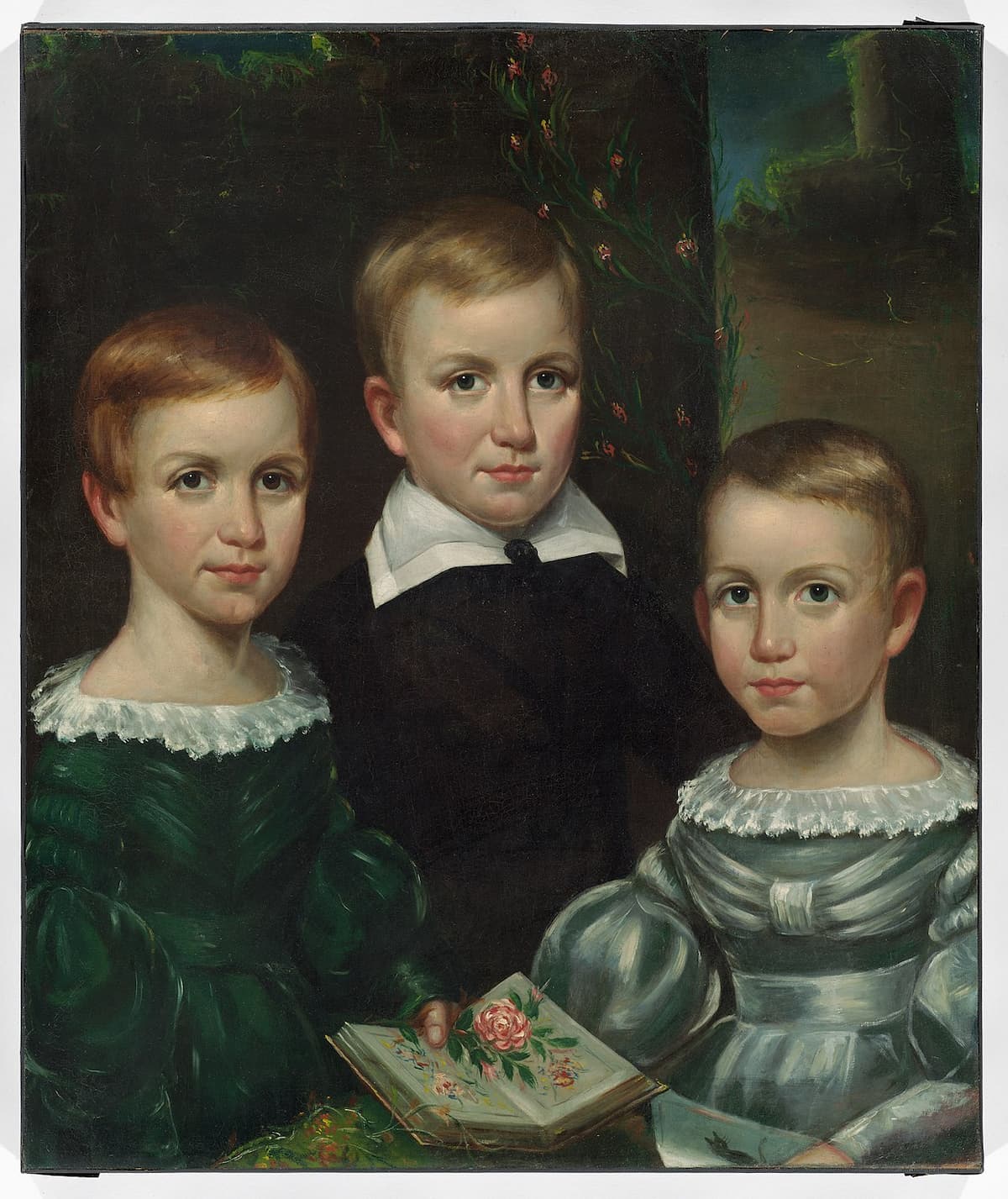

Painting of the Dickinson children (Emily on the left)

Her tense and private struggles took place during a time when Christianity was losing its grip as an overarching narrative, and Dickinson placed her innermost thoughts into poetry and not religion. Her worries about dying, “about annihilation in an empty cosmos emerged in a process of producing metaphors and watching the meanings emerge.”

Dickinson scribbled and jotted lines of poetry on old envelopes, scraps of wrapping paper, advertising flyers, and “she fiddled with them endlessly, finally copying them out carefully and storing them up in little packets, mainly for posterity.” Most lack titles, contain short lines, and use unconventional capitalization and punctuation. And, they primarily deal with themes of death and immortality.

Aaron Copland: 12 Poems of Emily Dickinson, No. 7 “Sleep is supposed to be” (Lynda Poston-Smith, soprano; Robert Carl Smith, piano)

Sleep is supposed to be,

By souls of sanity,

The shutting of the eye.

Sleep is the station grand

Down which on either hand

The hosts of witness stand!

Morn is supposed to be,

By people of degree,

The breaking of the day.

Morning has not occurred!

That shall aurora be

East of Eternity;

One with the banner gay,

One in the red array, –

That is the break of day.

Aaron Copland: 12 Poems of Emily Dickinson, No. 8 “When they come back” (Lynda Poston-Smith, soprano; Robert Carl Smith, piano)

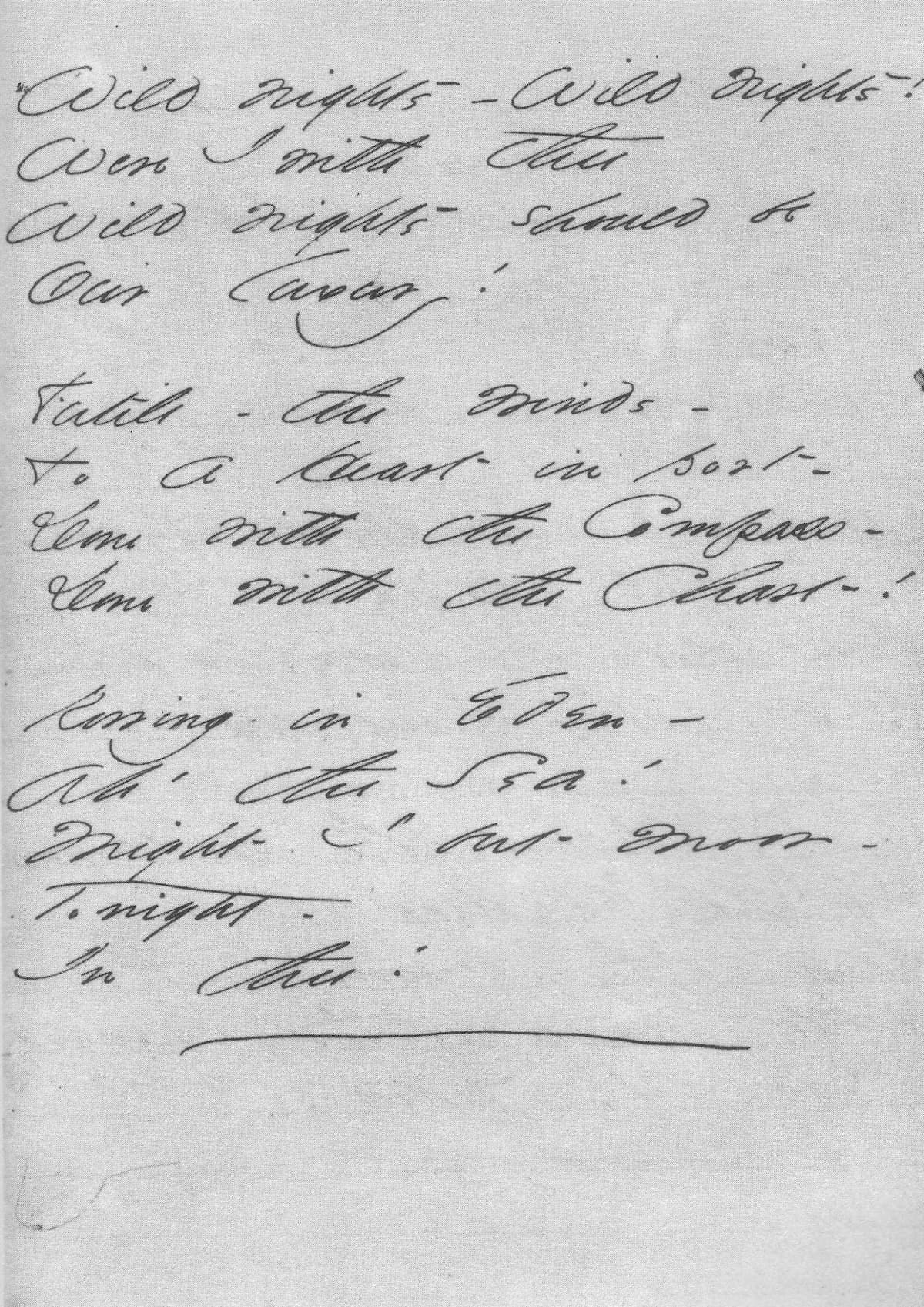

Emily Dickinson’s Wild Nights manuscript

Dickinson certainly challenged the existing definitions of poetry, experimenting with expression in order to free it from conventional restraint. A literary critic writes, “the speakers in Dickinson’s poetry are sharp-sighted observers who see the inescapable limitations of their societies as well as their imagined and imaginable escapes. To make the abstract tangible, to define meaning without confining it, to inhabit a house that never became a prison, Dickinson created in her writing a distinctively elliptical language for expressing what was possible but not yet realized.”

Dickinson wrote in an unapologetically noisy and musical way. In fact, her poems are constantly conveying a kind of musical experience trying to get a grip on the lack of meaning in the world. It is hardly surprising that her bareness, spareness, and “rhythmic variety makes her especially attractive to musical modernist, minimalist, and aficionados of atonality.”

Aaron Copland: 12 Poems of Emily Dickinson, No. 9 “I felt a funeral in my brain” (Lynda Poston-Smith, soprano; Robert Carl Smith, piano)

I felt a funeral in my brain,

And mourners to and fro,

Kept treading, treading, till it seemed

That sense was breaking through.

And when they all were seated

A service like a drum

Kept beating, beating, till I thought

My mind was going numb.

And then I heard them lift a box,

And creak across my soul

With those same boots of lead again.

Then space began to toll

As all the heavens were a bell,

And Being but an ear,

And I and silence some strange race,

Wrecked, solitary, here.

Aaron Copland: 12 Poems of Emily Dickinson, No. 10 “I’ve heard an organ talk sometimes” (Lynda Poston-Smith, soprano; Robert Carl Smith, piano)

Emily Dickinson’s Poems

While working on his 12 Poems of Emily Dickinson, Aaron Copland went to Dickinson’s bedroom in Amherst “to see what she saw out of the window.” Copland believed that she saw an American street of her time including a congregational church. As he writes, “She was an American woman of her time, above all an American woman hymn-writer of her time, but an extraordinarily radical one.”

Copland originally set “The Chariot,” and had no intention of creating an entire song cycle. However, as he explained, “I continued to add songs one at a time until I had twelve, with the poems themselves giving me my direction.” To a scholar, “Copland was able to parallel the compactness of the poems with an economy of musical resources both in the directness of the vocal line and the relative simplicity of the piano part.

Aaron Copland: 12 Poems of Emily Dickinson, No. 11 “Going to Heaven!” (Lynda Poston-Smith, soprano; Robert Carl Smith, piano)

For Copland, “the poems center on no single theme, but they treat subject matter particularly close to Dickinson: nature, death, life, eternity. Only two of the songs are related thematically. Nevertheless, the composer hopes that, in seeking a musical counterpart for the unique personality of the poet, he has given the songs, taken together, the aspect of a song cycle.”

Because I would not stop for Death –

He kindly stopped for me –

The carriage held but just ourselves –

and Immortality.

We slowly drove, he knew no haste,

And I had put away

My labour, and my leisure too

For his civility.

We passed the school, where children played,

Their lessons scarcely done,

We passed the fields of gazing grain,

We passed the setting sun.

We paused before a house that seemed

a swelling of the ground;

The roof was scarcely visible,

The cornice but a mound.

Since then ’tis centuries, but each

Feels shorter than the day

I first surmised

The horses’ heads were toward eternity.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Aaron Copland: 12 Poems of Emily Dickinson, No. 12 “The Chariot” (Lynda Poston-Smith, soprano; Robert Carl Smith, piano)