I was born into a musical family. My father was a cellist whose career spanned several years with the Budapest Symphony and thirty – eight years with the Toronto Symphony. My mother was an inspired piano teacher. Music permeated our home.

My parents were very pleased when at the age of three I could pick out the melodies my mother taught to her students. It was a sign. There was no question that I would become a musician. My mother envisioned me in a gorgeous long gown striding onstage! The lessons began – first the piano and then the cello.

I had a strict schedule to fit everything in – practicing the cello before school in the wee hours of the morning, doing homework after school and practicing piano after dinner. My mother listened while she did the dinner dishes.

“Play that again s-l-o-w-e-r!”

My father who was old school European, thought that the study of etudes, scales and exercises were essential. None of my cello teachers were strict enough for him. The Horvath household emphasized perseverance and perfectionism. I was dragged from one teacher to another. When the cello teacher du jour assigned me cello duets to play it was the last straw. My father decided that he would teach me. I resisted, as any self-respecting adolescent should. The battles began. Doors were slammed and tears were shed. Despite all of this I excelled.

Finally the time came for my official cello recital debut. The recital was to take place at the Art gallery of Ontario on a prestigious series. The newspaper reviewer was bound to be there and my father expected several of his colleagues to attend. Talk about pressure. Undaunted, I had chosen a very ambitious program.

Finally the time came for my official cello recital debut. The recital was to take place at the Art gallery of Ontario on a prestigious series. The newspaper reviewer was bound to be there and my father expected several of his colleagues to attend. Talk about pressure. Undaunted, I had chosen a very ambitious program.

I was prepared, and excited. My father was a wreck. We arrived early to the gallery, my father ashen, clutching his stomach. He slinked into a seat at the back of the hall next to my mother. Sitting within my line of vision was forbidden I had told them.

At concert time out I came out with confidence. I opened the program with the third Bach Solo Suite in C, a challenge even for the most seasoned performer. I sat down and dug my endpin into the floor – or so I thought – and with panache, I launched into the opening note of the Prelude. To everyone’s horror my endpin skidded across the floor. I grabbed the instrument with my body and regained control of my escaping cello without missing a beat. My father though, almost passed out. I brought the suite to a close without further mishaps and I left the stage to enthusiastic applause.

Backstage I composed myself for the next work, just a light little ditty – The Rococo Variations of Tchaikovsky. Surely this would impress everyone at the concert!

While I focused on the Herculean task, unbeknownst to me, my father combed the audience for a sharp object. Aha. He found someone with a penknife. He climbed onto the stage and crawled on his hands and knees to the center of the stage where he dug a hole for my wayward endpin. Then quickly, he slid back into his seat at the back.

I waltzed out for my next number just the picture of poise. I sat down and looked for a likely place in the wood floor to jam my endpin. I didn’t see a hole. My mother’s best friend was sitting in the prohibited first row. Much to my chagrin she pointed wildly and in her strongly accented English she bellowed, “Jan-attte! Your Daddy made a hole! Your DADDY made a HOLE!”

Despite this debacle, my father was satisfied enough to start thinking about my future. Only the best teacher would do, the great cellist and pedagogue Janos Starker at Indiana University.

I was terrified. I had heard stories about Starker. He was daunting with his bald head, chiseled features and black eyes and his playing was perfection itself. The next time Starker performed with the Toronto Symphony my father, despite my protestations, approached Starker. He generously agreed to hear me play. Anything for a fellow Hungarian.

The next day we went to Starker’s hotel room. It reeked of cigarette smoke. Starker was languidly relaxing in an armchair drinking a scotch on the rocks. I nervously started to set up. I planned to play the Rococo Variations again, something I felt I knew well, but he was so intimidating that I started to shake. Starker leaned back into the deep leather chair, arms and legs crossed. His eyes bored into me. Prove yourself and don’t waste my time was his message.

He interrupted me abruptly after I had played only a few minutes and tersely said, “You have a lot of physical development to do.” What does he mean by that, I thought? Run around the track? Disappointed and puzzled we hurried home.

It took a few days but I decided that I’d show him. I’d take a year off and practice really hard, all day if necessary.

The following school year I wrote a letter to Starker about my intentions to come to Indiana to audition for him again. Much to my surprise, Starker called my father and by phone accepted me as his student. My dad was pleased.

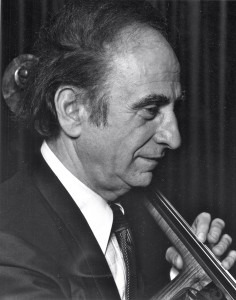

Photo 1 : George Horvath Credit : Janet Horvath

Photo 2 : Janet and George Horvath Credit : Janet Horvath

Fantastic Janet! Such intimate (and funny) detail. I can see it all perfectly and almost hear it too. Can’t wait to read more!

What a funny story. I laughed so hard that the tears were rolling down my face. I am not a musician and I had no idea of some of these behind the scenes calamities and tribulations. I can’t wait for more.

by the way it was quite complicated to leave a comment

This is such an inspiring article! What strikes me most is the honesty between the lines and the warmth of affection for family. It is obvious that Ms. Horvath has not led an easy life, but her humor and natural story-telling are a lovely reminder of the richness of one life. I also love the pictures! They make this much more than just a story. Thank you for printing this.