The German composer George Frideric Handel (1685–1759) worked in Britain and was good friends with the painter Joseph Goupy (1689–1759). In London, Handel lived a good life and was considered one of the great voluptuaries of the age, known for his excessive eating and drinking.

One of the most common images at a performance would have been Handel at the keyboard, and he would have been seen at the instrument at the numerous Messiah benefits held for the Foundling Hospital and his Lenten oratorio series.

Bathasar Denner: George Frideric Handel, ca. 1726

Joseph Goupy worked with Handel as early as 1727, when he did the scenery for Handel’s Riccardo I. He was employed also by the Royal Academy of Music, which hired him to paint sets for Handel’s operas. In 1742, Goupy painted a portrait of Handel for the Prince of Wales. By 1743, however, he and Handel were on the outs and in 1744–45 were having major quarrels.

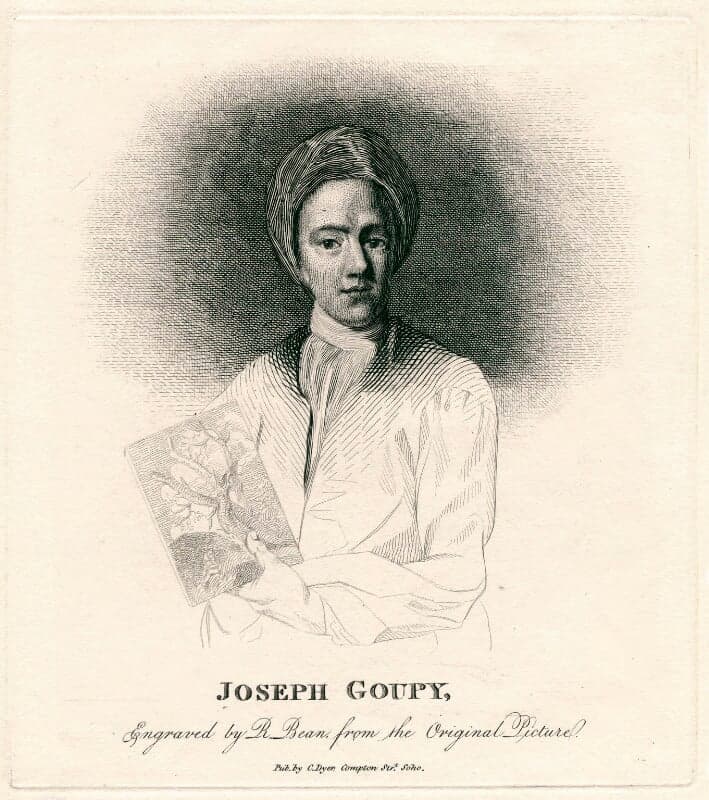

Richard Bean: Joseph Goupy, 1810–17 (National Portrait Gallery)

George Frideric Handel: Riccardo Primo, HWV 23 – Act I: Ouverture: Largo( Les Talens Lyriques; Christophe Rousset, cond.)

In the painting, A Charming Brute, Handel is shown in his characteristic pose at an organ but has been given the snout of a pig. He is surrounded by images of gluttony and avarice. What prompted this painting seems to have been Handel’s refusal to compose operas for the aristocracy (Goupy had spoken to Handel about an opera at the request of the Prince of Wales) and to continue to compose ‘for himself’ with his oratorios. Another situation that angered Goupy was a dinner with Handel where the composer warned the artist that the dinner would be ‘plain and frugal.’ After the meager dinner, Handel excused himself and vanished for a time. Goupy went to look for him and found him ‘sitting at a table covered with such delicacies as he had lamented his inability to afford his friend.’ Goupy left the house in a rage. His painting, A Charming Brute, shows just how angry Goupy was at his former best friend.

George Frideric Handel: Messiah, HWV 56 (1751 Version) – Part II: Chorus: All we like sheep have gone astray (Oxford New College Choir; Academy of Ancient Music; Edward Higginbottom, cond.)

To express his feelings, Goupy chose to represent Handel as a hog. Goupy felt Handel had been a false friend and, in the painting, exposed him as a ‘morose, ill-bred, ill-mannerly Fellow.’ Surrounding the hog composer are hams, fowls, and many ‘sorts of dainties.’

Goupy: The Charming Brute, ca 1742 (Fitzwilliam Museum)

The Fitzwilliams’ description lays out the number of insults in the painting: Handel is presented as an obese half-man, half-hog, seated on a dripping beer barrel before an organ, his hands barely able to reach the keyboard over his vast belly. A dwarfish servant holds up a mirror in front of this monster. A joint of ham and a dead fowl hang from the side of his instrument. Behind him are scattered oyster shells, while before him are various musical instruments. A pig’s head on the floor reinforces the insult. … On a scroll in front of the composer are the words “pension, benefit, nobility, friendship”’. On Handel’s head is an owl, the bird of solitude – where his grotesque head is testimony to his quick temper, the owl is the sign of his habit of shutting himself away.

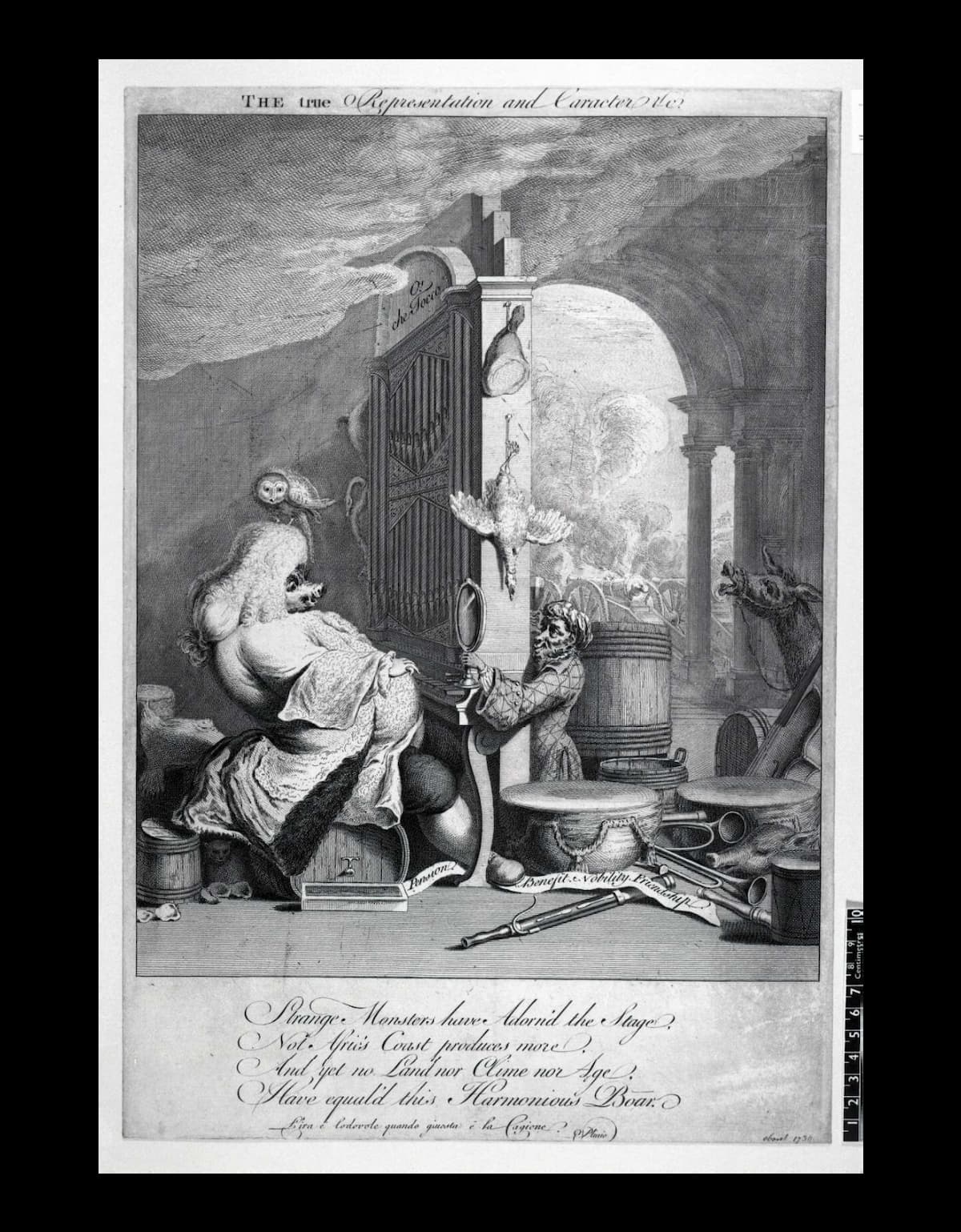

A decade later, Goupy made an engraving of the painting. It bears a little poem below:

Strange Monsters have Adorn’d the Stage,

Not Afric’s Coast produces more,

And yet no Land nor Clime nor Age,

Have equal’d this Harmonious Boar.

It calls him a monster but a harmonious one. In smaller letters below is a self-justifying line in Italian attributed to Pliny: L’ira è lodevole quando giuesta è la cagione. Plinio’. (Anger is praiseworthy when the cause is just).

The image isn’t identical to the painting: the patient horse is now a braying donkey, the ham and the fowl have changed places, there’s a cannon outside the door fired by the blazing music of the organist, the top of the organ says ‘O! che Tocca’ (Oh! That touch), the archway is more elaborate, etc., but the image of the half-animal, grossly fat composer who can barely reach the keys remains as vicious as ever.

Goupy: The True Representation and Caracter etc., 1754 (British Museum)

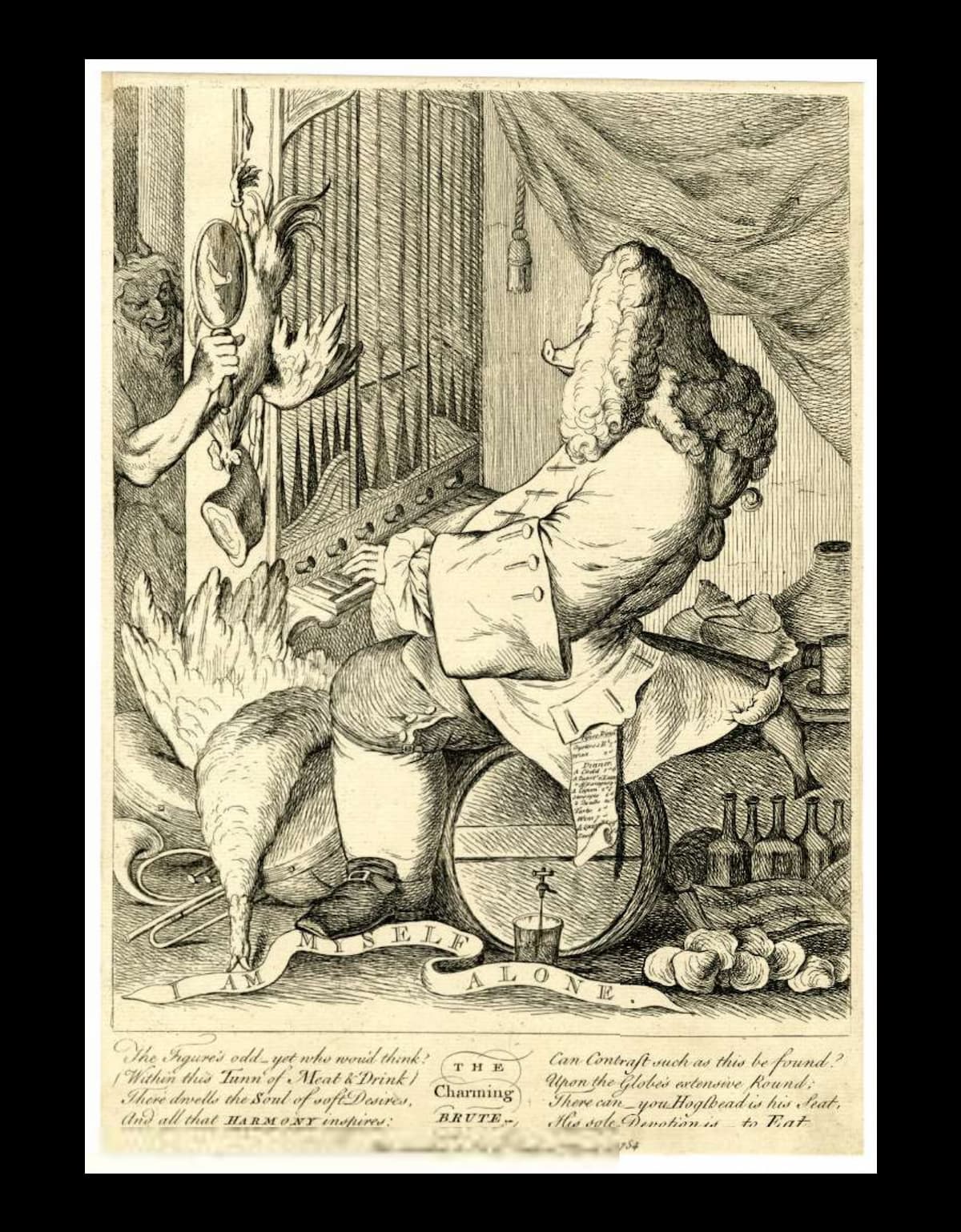

In a smaller, more focused engraving, by an anonymous hand, the image has been reversed, and the scroll now reads ‘I am myself alone’. The ugly servant holding up the mirror now has the devil’s horns. Handel’s swollen legs look more like contemporary illustrations of men with gout, and out of his pocket falls a detailed dinner bill. He’s still seated on a barrel of wine; there are oysters on the floor, a turbot under his coat, and bottles of wine around him. His hands are less corpulent and can easily reach the simplified organ keyboard.

The poem below reads:

The figure’s odd – yet who wou’d think?

(Within this Tunn of Meat & Drink)

There dwells the Soul of soft Desires,

And all the HARMONY inspires:

Can Contrast such as this be found?

Upon the Globe’s extensive Round;

There can yon Hogshead is his Seat,

His sole Devotion is – to Eat

Below the poem, it reads ‘’Pub according to Act of Parliament. March 21st. 1754.’. In other versions of this image, the devil with the mirror is missing.

Anonymous: The Charming Brute, 1754 (British Museum)

George Frideric Handel: Judas Maccabaeus, HWV 63 – Part III: To our great God be all the honour given (Schlierbacher Motet Choir; Schlierbacher Chamber Orchestra; Thomas Fey, cond.)

Goupy’s anger proved expensive to him: Handel promptly cut him out of his will. He was rumoured to be leaving Goupy as much as £5,000 (equivalent to £1.25 million in today’s money), but as Handel only left some £3,000 in bequests, that figure may be somewhat exaggerated (or had an extra zero added). Nonetheless, although Handel died wealthy, Goupy died with little money and, in his last years, had to sell pieces from his collection. Goupy’s painting remained in his hands until he sold it in 1765 as part of his first fund-raising auction six years after Handel’s death (and 4 years before his own). The painting is now at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, and the engravings can be found in a number of collections.

Goupy’s vicious insider’s view is not one of the contemporary imaginings of Handel, but it gives us an idea of how high emotions could run and the cost of making fun of someone who had the advantage over you.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter