Noa Kageyama is a performance psychologist who focuses on teaching performing artists to apply principles of sports psychology to demonstrate their full potential even under pressure. Noa has a thriving career. In addition to maintaining his popular performance psychology blog, The Bulletproof Musician, he serves on the faculty of the Juilliard School in NYC, the Cleveland Institute of Music, and the New World Symphony. In this interview, Noa will tell us how he transformed from a violinist to a performance psychologist.

Noa Kageyama © Rosalie O’Connor

According to Noa, sport (or performance) psychology is a multidisciplinary field, drawing from fields like psychology, kinesiology, and physiology to examine how psychological factors affect performance, as well as how engaging in sport and exercise affects our psychology as well. Basically, it’s the study of how to optimize performance under pressure and maximize the mental health and functioning of performers.

To let our readers know about you, would you like to give us a brief introduction of yourself?

Sure! The short version of the story is that I started playing the violin at age 2 1/2, and always assumed that I would go into music. I was pretty serious about it from about the time I was 5 or 6, had great teachers along the way (often driving anywhere from 3-8 hours, or flying for lessons), did competitions, summer festivals, chamber music, theory, and all the rest.

I continued through college (Oberlin) and grad school (Juilliard), until I began to realize at Juilliard that I just didn’t have the sort of burning passion for music that my friends had. At about that same time, I was taking a sport psychology class, and beginning to realize that I had always had other interests, and maybe this could be a slightly different direction that I could go in, without completely giving up everything that I had worked towards for so many years.

After Juilliard, I went to Indiana University to pursue a PhD in psychology, with a focus on sport and performance psychology. Which eventually led to my starting the bulletproofmusician.com blog and podcast, returning to Juilliard to teach performance psychology, and a career that has ended up blending my music background and psychology training, where I teach musicians how to utilize performance psychology to optimize their daily practice and performing.

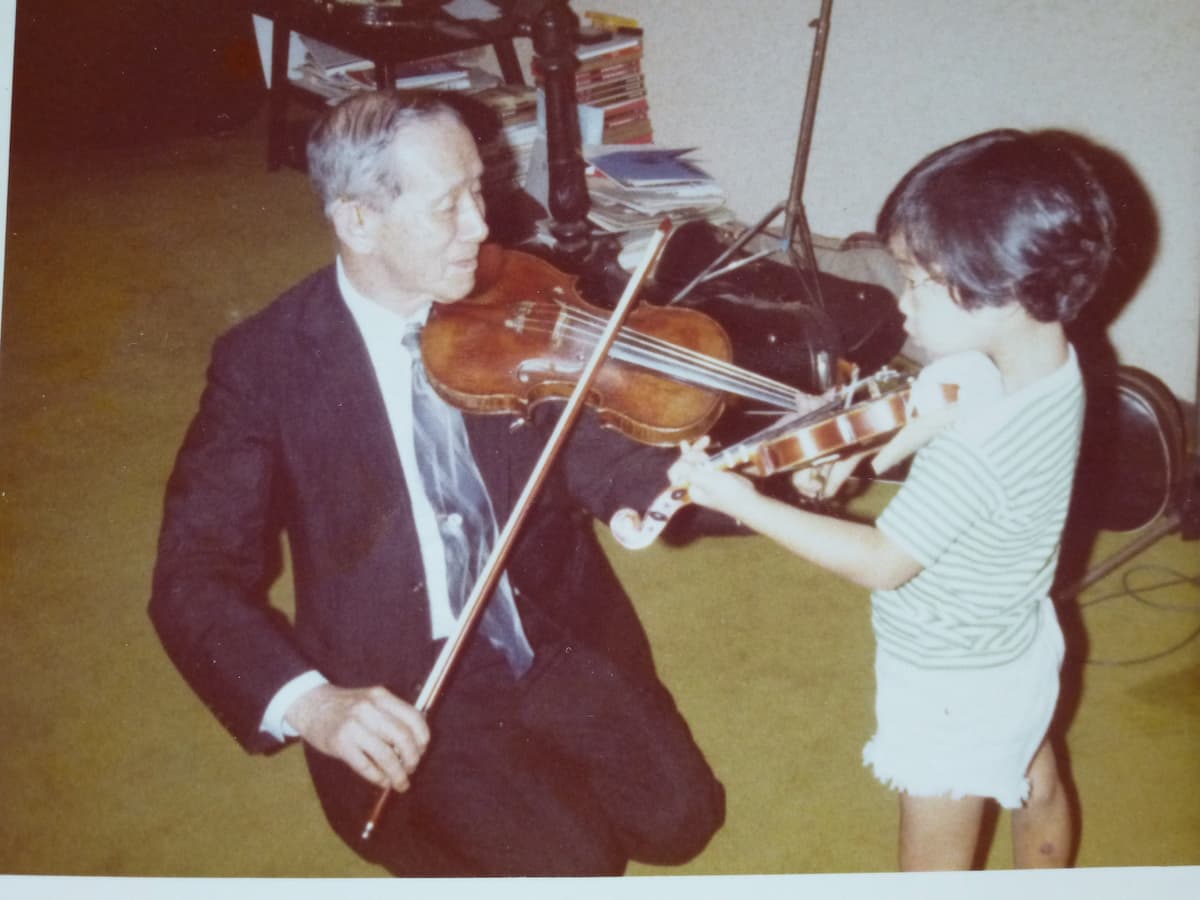

You studied with Shinichi Suzuki when you were young. How was the experience of taking lessons from him? How was the music-learning culture there back then?

Noa Kageyama’s lesson with Dr. Shinichi Suzuki at age 6, 1982

I was 5 when I studied with Dr. Suzuki, so many of my memories are just flashes and glimpses of moments. But I remember him always having a lot of energy and being very demonstrative and enthusiastic. Even though I didn’t speak Japanese, even without my mom translating, I felt like he was able to communicate what he wanted me to do through his body language.

I feel like he had the energy and spirit of a little kid as well. I remember one time I was throwing a paper airplane around in the lobby area of his school, and it accidentally hit him in the back. My mom was mortified and so apologetic, but he just laughed and smiled and threw it back at me.

As far as the music-learning culture goes, this is less about Dr. Suzuki, and more about the 80’s and 90’s in general, I made a lot of great friends, and had a ton of great moments that I’ll always remember, but one difference between then and now, is that I don’t think nerves or pressure or the mental side of performing was something that any of us ever talked about. It’s something we all experienced and had to deal with in our own way, of course, but I think it’s something that is much more openly talked about nowadays. There doesn’t seem to be as much of a stigma around nerves and anxiety when it comes to performing.

Which there should never have been in the first place, because it’s something we all experience, but fortunately, it seems to be something that more and more folks are willing to acknowledge and share their own experience of.

When you studied at Juilliard, what was your initial goal?

I always assumed that my goal was to win a big competition and have a performing career of some kind. I just thought that that was what musicians did. I never really thought about orchestra, or a chamber music career, or teaching.

And to be honest, I never really even asked myself whether I wanted to be a musician or not. I started so early, and just stayed on the path without question for so long, that doing anything else never really occurred to me.

It wasn’t until I was probably in my second year at Juilliard when I started asking myself what I wanted to do “when I grew up,” or when I finished at Juilliard, and started to realize that all of the things I was ostensibly working towards, were not actually sparking much joy, and didn’t really feel like “me.”

That’s when I started entertaining the idea of pursuing grad studies in psychology – even though I had no idea at the time where that would lead!

Your biography mentioned that Don Greene’s class “Performance Enhancement for Musicians” inspires you to pursue psychology. Can you share one or two things you learned from the class that completely changed your mind about music performance and practicing?

© Rosalie O’Connor

There were a number of strategies and skills that were pretty transformative, but the biggest thing I learned was that practicing more effectively and performing more effectively were skills that can be learned and improved upon.

For most of my life, practicing was just about repetition, repetition, repetition. My approach wasn’t especially strategic or thoughtful at all, I just tried to get things right, and played them until they sounded better. This can be a very frustrating process, of course, and it can feel sometimes like things are never going to get better. Especially when the improvements you do make, don’t translate to performance.

With performing too, I just assumed that if I performed enough, at some point, things would feel better and things would be more consistent. But even after two decades of performing, every performance felt random. I never knew if it was going to be a good day or a bad day. Even when I had practiced a lot, things would still be pretty hit or miss. And I almost never played as well as I knew I could.

Learning how to practice more effectively and learning how to prepare for performances – especially how to get into a better headspace, and how to stay laser-focused in a performance (and what exactly to think about or focus on during a performance) changed my experience on stage. It was incredibly empowering to discover that I had control over my learning rate, and that I was also in charge of how well performances went too.

For new readers interested in your website, what is the first thing you would like them to start with?

I think the best place to start is either with the Start Here page (where you learn a little about my background, and can select from some curated articles and podcast episodes to start with), or even better perhaps, the Mental Skills Audit. The MSA takes about 4 minutes and will give you a quick sense of what your mental strengths and weaknesses are, and suggests a few articles in each mental skill area that would be most useful to start with.

Do you still play the violin? Besides teaching, coaching, and managing Bulletproof Musician, would you like to share one or two things you do when you have time?

The last time I really played was a Janos Starker studio class in December 2000. I was doing a performance diploma at Indiana University during the year I was applying for graduate programs in psychology, and the cellist in the quartet I was playing in studied with him. I’ve had to come out of “retirement” a couple times for family events, in the decades since, but I haven’t really touched it other than that.

Other than spending time with my wife and kids, I started training in Brazilian jiu jitsu about 6 years ago. That really messes up your hands, so I never would have been able to explore that if I still had to play the violin!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter