Pearl Necklace

noun

a way of carrying out a particular task, esp. the execution or performance of an artistic work or a scientific procedure.

• skill or ability in a particular field

• a skillful or efficient way of doing or achieving something

Technique lies at the foundation of piano playing, and good technique can serve the beginner student right through to advanced level. However, it should never be the “be all and end all”. Rather, it should serve the music – to create when required, for example, the lightest staccato, the most cantabile melodic line, a bubbling Alberti bass, sprightly trills and tremolandos, the most fluid legato.

“Everything you do, sounds. All your movements, both intended and unintended, have their effect on the sound you produce”

– Alan Fraser, pianist & pedagogue

Pianists are often praised for having “fine technique” or “superb technique”: this can range from obvious things such as physical agility/velocity and stamina to more esoteric, “hidden” aspects such as arm weight, wrist rotation, and alignment. These days, with a tendency amongst younger pianists to place technique above all else, piano “technique” has come to mean sheer physical capability, speed and sound production (usually too loud!) without a true understanding of how a particular technique specifically relates to the music, and the effects the composer has in mind.

Debussy: Jardins sous la pluie (Arrau)

Perhaps the most obvious example of this is staccato, of which there are different kinds:

• Arm staccato gives equal measure to each note and is particularly useful for a crisp, short or bouncy sound. Involve the forearm and keep the wrist soft. Avoid pure wrist staccato as this pulls up the fingers and creates tension. Aim for a free drop of the arm and then bounce off the keyboard on the rebound.

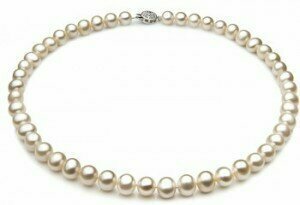

• Jeu Perlé literally “pearly playing”, this is particularly useful for semi-quaver passage work in Mozart and the like, also in Debussy, where such passages should be played quickly, lightly and clearly, and where too much obvious articulation would create dryness. It is a type of staccato playing that creates the tiniest sense of separation between each note (like the knots between the pearls in a necklace), and requires small movements and a close attack.

• Finger staccato/flicking staccato Possibly the hardest staccato technique to perfect, this requires the fingers to flick off the keys and back towards the palm of the hand. Beware of tension in the hand and wrist when practising this technique, and employ the alignment of arm and wrists to fingers.

A pianist who has fully studied, understood and absorbed the composer’s intentions and instructions in the score, will know what kind of staccato technique to employ for a particular genre, section or passage.

Mozart: Piano Sonata K311 – I. Allegro con spirito (Uchida)

When starting out with any new aspect of technique, whether teaching it or doing it for yourself, it helps to enlarge the movement and to practice it away from the piano. Don’t practice technique in isolation, but rather understand how it should be employed in your music and then make a technical exercise out of a small passage or section from that music. Doing exercises like those by Czerny or Hanon are, in my view, less worthwhile than a technical exercise you have devised yourself to practice a particular aspect of your repertoire; it is also more interesting! Above all, any technical exercise – from simple scale patterns to an intricate etude – should be played musically.