Édouard Dubufe: Charles-Valentin Alkan, ca. 1835

The reclusive French composer Alkan was, at the height of his fame, ranked as a virtuosic pianist on the level of Chopin and Liszt. He lived his entire life in Paris, attending the Paris Conservatoire beginning at age 6. In the 1830s and 1840s in Paris, he performed in the greatest salons in Paris, but would occasionally vanish, withdrawing from public view. Eventually, by 1848, he retired completely from performance, devoting his time to composition. He emerged again in 1873 for a period, reaching a new body of French musicians.

Born to the family name of Morhange, Alkan and his five brothers and his sister all became musicians under the name of Alkan, which was their father’s first name. In his years of study at the Conservatoire, he was awarded the premier prix for solfège at age 7, the premier prix for piano in 1924, for harmony in 1827, and for organ in 1834. Cherubini described the 9-year-old musician as ‘extraordinary’ on the piano. Outside the conservatoire, he was a close friend of Chopin, George Sand, and others in their social circle. Yet, a shyness and misanthropy began to creep into his life and he frequently vanished from the public eye.

The majority of his compositions were for the piano and his greatest work is considered the set of 12 etudes in the minor, Op. 39, that he published in 1857. This set of 12 etudes opens with set of three miscellaneous pieces (Op. 39, 1-3), followed by a 4-movement symphony (Op. 39, Nos. 4-7), a three-movement piano concerto (Op. 39, Nos. 8-10), an overture (Op. 39, No. 11), and closes with a set of 25 variations (Op. 39, No. 12).

We can hear from the very beginning, Comme le vent, that Alkan is going to make substantial demands on his performer.

Alkan: 12 Etudes dans les tons mineurs, Op. 39, No. 1. Comme le vent (Jack Gibbons, piano)

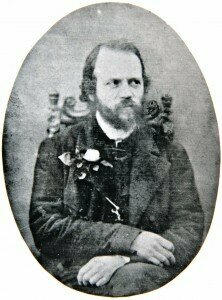

One of two known photographs of the reclusive Alkan, date unknown

No. 4. Symphonie pour piano seul: I. Allegro

The second movement is a funeral march, as was the style at the time, but, harking back to the Classical period, the third movement is a minuet, albeit in a minor key.

No. 6. Symphonie pour piano seul: II. Menuet

The finale launches out at a terrific speed of Presto. An American pianist has simply described the work as “a ride in Hell,” where one is constantly thrown forward. At the same time, its weight and brilliance can successfully balance the other parts of the ‘symphony.’

No. 7. Symphonie pour piano seul: IV. Finale

The Symphonie is followed by a Piano Concerto for Solo Piano. The first movement is nearly half an hour long and again, is a fury of sound. The second movement, however, provides us with one of the first moments of repose in the entire group of etudes.

No. 9. Concerto pour piano seul: II. Adagio

After the Concerto pour piano seul, we have a concert overture, and then a set of varations under the title of Le festin d’Ésope (Aesop’s Feast). The work appears to be a mixture of Aesop’s animal fables, and of a tale of Aesop where he was to provide 2 feasts for philosophers: one with food of the best quality, and another with the food of the worst quality. For both feasts, Aesop created a menu based on tongue, as that has the power for both good and evil. And so in this set of 25 variations, based on an original theme, we have the original theme dressed in every possible way for our feast. You’ll hear military rhythms, great crashing chords, and flying filigrees of notes.

No. 12. Le festin d’Ésope

Alkan, around 1850

Oh, and about his death. Alkan died in Paris at age 74, on 29 March 1888. The pianist Isidor Philipp circulated the tale that Alkan had died, crushed by his bookcase when the studious and solitary composer was reaching for a big book on the top shelf. In 1988, musicologist Hugh Macdonald, however, found a letter by one of Alkan’s pupils saying that his teacher had been found in the kitchen, on the floor under a heavy coat rack that he might have pulled down on himself as he fainted. Carried to his bed, Alkan died later that evening.