Antonín Dvořák

Antonín Dvořák

Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op. 104, B. 191

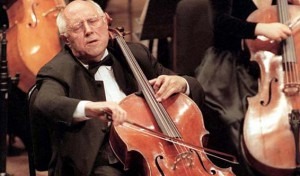

Mstislav Rostropovich

Moscow Radio Tchaikovsky Symphony Orchestra

When I was a student I would often sneak into the Toronto Symphony Orchestra concerts. My father, who was a member of the cello section, would bring a program home. I knew my way around the basement boiler rooms and I’d hurry through the dank, dark area emerging in the hall. I’d race up to the top gallery brandishing the program, as if I had already shown my ticket.

I was particularly excited one day in August of 1968 because Mstislav Rostropovich, one of the greatest cellists of all time, was scheduled to perform a work, which was written for him — Shostakovich Cello Concerto No 1. Rostropovich had arrived in Toronto several days before the rehearsal and with time on his hands, he had generously offered to read through a piece of music with the University of Toronto student orchestra. I was elated to be invited to attend.

He chose the Antonín Dvořák Cello Concerto — a work that Rostropovich played gloriously with his gorgeous sound and larger-than-life personality. The students had practically no advance notice. The next day everyone including all the students and faculty members gathered excitedly in the auditorium. I was there too, sitting on the edge of my seat.

The U of T Orchestra conductor was not particularly well liked by the students. They were silently thrilled when Rostropovich stopped the orchestra time and time again to indicate to the conductor where things needed to be improved. This concerto has several important solos for three French horns including a major trio in the slow movement. One of my friends was playing the horn and he was a bit green when it came to transposition — the horn players must learn to read the music in one key while playing in another “at sight.”

Eventually, the orchestra played the famous horn trio in the second movement and sure enough, someone in the horn section screwed up the transposition. (I didn’t dare look up onto the stage.) Rostropovich stopped abruptly and made them play it again. My horn-playing friend was quaking. It wasn’t any better the second time. Rostropovich halted the orchestra again and to our surprise he proceeded to play all three horn parts simultaneously on the cello. It was incredibly beautiful. My bumbling horn-playing friend was meanwhile frantically trying to transpose his part in his head now that he’d heard what the notes were supposed to be. Everyone sighed with relief when the students played it correctly the third time.

The next morning Rostropovich rehearsed the Shostakovich Concerto with the Toronto Symphony, Seiji Ozawa conducting. After the rehearsal Rostropovich went to a restaurant for lunch. The café happened to have the radio on. While Rostropovich was eating he heard the news that Russian tanks had that very morning rolled into Prague to put down the yearlong uprising by the Czech people against Communism. The date was August 20th 1968. Later it would be known as the Prague Spring. Rostropovich raced to the pay telephone. He called Ozawa to ask him if it would be possible under the circumstances to change the program. He wished to play the Dvořák Cello Concerto that night instead of the Shostakovich. Ozawa agreed.

The next morning Rostropovich rehearsed the Shostakovich Concerto with the Toronto Symphony, Seiji Ozawa conducting. After the rehearsal Rostropovich went to a restaurant for lunch. The café happened to have the radio on. While Rostropovich was eating he heard the news that Russian tanks had that very morning rolled into Prague to put down the yearlong uprising by the Czech people against Communism. The date was August 20th 1968. Later it would be known as the Prague Spring. Rostropovich raced to the pay telephone. He called Ozawa to ask him if it would be possible under the circumstances to change the program. He wished to play the Dvořák Cello Concerto that night instead of the Shostakovich. Ozawa agreed.

As the musicians arrived for the performance at Massey Hall, my father among them, the musicians were advised that they would be sight-reading the Dvořák concerto. My horn playing friend and I were sitting in the gallery in the front row and we could easily see that as Rostropovich played, especially during the heart rending slow movement, tears were streaming down his cheeks. It was one of the most outstanding moments in our musical lives. Of course he was bravely making a political statement. Dvořák of course was Czech. Eventually Slava’s frequent outspoken comments resulted in his exile from Russia.

Slava was a committed humanitarian. After Armenia’s horrendous earthquake in 1988, which killed 45,000 people and left another 500,000 homeless, Slava organized and performed several benefit concerts for the victims. And in 1989 he traveled to Berlin to play solo cello in front of the Berlin Wall as it was being torn down. His foundation builds children’s hospitals in underserved rural regions of central Russia.

Rostropovich was known for his emotional and volatile temperament. When he became the music director of the National Symphony, a position he held for almost 20 years, a glare from him was devastating. He scrutinized the cello section especially, and he often grabbed someone’s cello to demonstrate. Steven Honigberg, a young cellist in the NSO at the time, experienced Slava’s notorious eagle eyes (and ears.) “Stevechik,” Slava called out to him during a rehearsal, “bad fingering!”

Rostropovich’s high standards extended to his daughter Olga, who in an interview with Tim Janof for the International Cello Society relates the following story. “He had gone out for awhile. Thinking I had a few hours to myself, I decided to read a book instead of practice, since I didn’t enjoy practicing all that much. As luck would have it, my father forgot something, or at least he pretended to forget something, and he returned home unexpectedly. When he opened the door, there I was lying on the sofa with my book. He became so furious that he grabbed my cello and started chasing me around the house with it, ordering me to stop running so that he could kill me. I quickly ran downstairs and out the front door, but that didn’t stop him, so I ran along the circular road that surrounded our cluster of houses, and there was Dmitry Shostakovich taking his daily stroll concentrating on his composing. Shostakovich pleaded with my father as he ran by still waving my cello in the air, ‘Slavachka, have a fear of God! Have a fear of God!’ he said trying to calm my father down. Needless to say, it was quite a scene.”

Rostropovich inspired many composers to write cello and orchestral works for him. He performed 220 premiers — 150 for the cello and 70 as a conductor. Perhaps another cello colleague says it best — Lynn Harrell,” He was a gigantic virtuoso, but one who threw caution to the winds to such an extent that the cause of drama and the intensity of the music itself were uppermost.”

More Blogs

-

Augusta Holmès: A Composer Who Wrote Music Bigger Than Life “I must show the males what I’m made of!”

Augusta Holmès: A Composer Who Wrote Music Bigger Than Life “I must show the males what I’m made of!” -

Classical Music Unfinished and Restored IV Why did Schubert leave so many works incomplete?

Classical Music Unfinished and Restored IV Why did Schubert leave so many works incomplete? -

The Trinity of Music Deepen your understanding of music's fundamental elements here

The Trinity of Music Deepen your understanding of music's fundamental elements here -

Singer Maria Malibran: Her Tortured Life and Death Read about opera's most fascinating tragedy

Singer Maria Malibran: Her Tortured Life and Death Read about opera's most fascinating tragedy

Thank you Janet. A wonderful article about a giant of the music world. I think I was subbing in the TSO on that occasion. I remember doing the Dvorak with him. On another visit, after I joined the orchestra full time, he and the Russian emigres in the band had a party the night before the first rehearsal that went until sun up. Rostropovitch came in and played with incredible energy and intensity. There was no sign of fatigue or hangover which was incredible given how much vodka we had been told had been consumed by all, including Slava. For me he was unmatched; as close to perfection as is humanly possible.