A recent concert by the distinguished Emerson String Quartet (Eugene Drucker, violin; Philip Setzer, violin; Lawrence Dutton, viola; Paul Watkins, cello) at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. paired Dmitri Shostakovich’s String Quartet No. 15 in E-flat minor, Op. 144 (1974) with Franz Schubert’s Quartet in D-minor, D. 810 “Death and the Maiden” (1824). The quartet’s superb musicianship, and their amazing responsiveness to each other, created rich and beautiful sounds, which according to The New York Times (quoted in the program notes) “… establishes a chromatic scale of timbres that range from dry and tart over clean and zesty all the way to lustrous and singing. Listening to them pass tiny rhythmic motifs around the group, (.…) these timbres were evenly calibrated”.

A recent concert by the distinguished Emerson String Quartet (Eugene Drucker, violin; Philip Setzer, violin; Lawrence Dutton, viola; Paul Watkins, cello) at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. paired Dmitri Shostakovich’s String Quartet No. 15 in E-flat minor, Op. 144 (1974) with Franz Schubert’s Quartet in D-minor, D. 810 “Death and the Maiden” (1824). The quartet’s superb musicianship, and their amazing responsiveness to each other, created rich and beautiful sounds, which according to The New York Times (quoted in the program notes) “… establishes a chromatic scale of timbres that range from dry and tart over clean and zesty all the way to lustrous and singing. Listening to them pass tiny rhythmic motifs around the group, (.…) these timbres were evenly calibrated”.

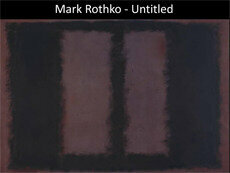

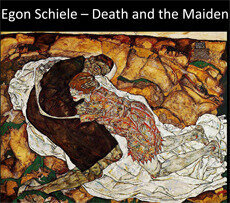

Both quartets were composed towards the ends of Shostakovich’s and Schubert’s lives, and just as in Schubert’s ‘Winterreise’, the listener is confronted by dreams of hope, love and friendship, only to find that the journey ends with a lonely soul wandering through a barren landscape towards death and silence. The connection between the two works, with their sense of tragedy, also established in my mind a close relationship with the late paintings of Mark Rothko and with Egon Schiele’s painting, ‘Death and the Maiden”.

Both quartets were composed towards the ends of Shostakovich’s and Schubert’s lives, and just as in Schubert’s ‘Winterreise’, the listener is confronted by dreams of hope, love and friendship, only to find that the journey ends with a lonely soul wandering through a barren landscape towards death and silence. The connection between the two works, with their sense of tragedy, also established in my mind a close relationship with the late paintings of Mark Rothko and with Egon Schiele’s painting, ‘Death and the Maiden”.

Shostakovich

String Quartet No. 15 in E-Flat Minor, Op. 144

(Kremer, Phillips, Kashkashian, Yo-Yo Ma)

Shostakovich composed his Fifteenth Quartet — the last of his string quartets – in 1974, one year before his death. The very names of the six movements, titled Elegy, Serenade, Intermezzo, Nocturne, Funeral March and Epilogue, already set the tone of the piece — all in the tenebrous tonality of E-flat minor. The adagio tempo, carried throughout the entire work, shades and shapes the composition, giving it the atmosphere of a requiem. Each of the movements leads from one into the other — the first movement, elegy, resembling a fugal chant, where the second violin, playing the melody, suggests a folk tune. Single tones and a sort of a waltz occur in the serenade which follows, after which the short intermezzo is led by a violin cadenza which opens into the exquisite nocturne. The fifth movement, as its name indicates, is like a funeral march, almost as if a bugle call from the battlefield, which then reappears in the finale, epilogue, itself leading towards death and silence. Paul H. Epstein remarks in the program notes that “The overwhelming experience of Shostakovich’s music is that of direct transmission of mind, of human feeling. It is spiritual music without the religion of God or Beauty but possessing an intense human commitment and compassion”. In that spirituality, Shostakovich’s works find their counterpart in the music of Arvo Pärt and Henryk Gorecki and, for me, lead directly to the late paintings of Mark Rothko.

Shostakovich composed his Fifteenth Quartet — the last of his string quartets – in 1974, one year before his death. The very names of the six movements, titled Elegy, Serenade, Intermezzo, Nocturne, Funeral March and Epilogue, already set the tone of the piece — all in the tenebrous tonality of E-flat minor. The adagio tempo, carried throughout the entire work, shades and shapes the composition, giving it the atmosphere of a requiem. Each of the movements leads from one into the other — the first movement, elegy, resembling a fugal chant, where the second violin, playing the melody, suggests a folk tune. Single tones and a sort of a waltz occur in the serenade which follows, after which the short intermezzo is led by a violin cadenza which opens into the exquisite nocturne. The fifth movement, as its name indicates, is like a funeral march, almost as if a bugle call from the battlefield, which then reappears in the finale, epilogue, itself leading towards death and silence. Paul H. Epstein remarks in the program notes that “The overwhelming experience of Shostakovich’s music is that of direct transmission of mind, of human feeling. It is spiritual music without the religion of God or Beauty but possessing an intense human commitment and compassion”. In that spirituality, Shostakovich’s works find their counterpart in the music of Arvo Pärt and Henryk Gorecki and, for me, lead directly to the late paintings of Mark Rothko.

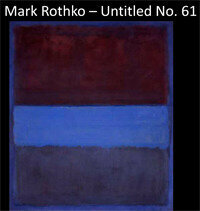

The ‘spiritual element’ is very much present in Rothko’s late, abstract paintings. After 1947, none of these works carry any title, leaving the interpretation open to the viewer’s imagination. Viewing these works, the spectator seems to become enveloped, almost immersed in these paintings — all without frames, without delineation. Darker hues shimmer and fuse through bands of color in varying widths — speaking of nothing but stillness and silence. For Rothko, they are anecdotes of the spirit, which in my mind can be linked to the different movements of Shostakovich’s quartet, in which the two violins, viola and cello respond to each other either in harmony or opposition – all within the frame of the composition.

The ‘spiritual element’ is very much present in Rothko’s late, abstract paintings. After 1947, none of these works carry any title, leaving the interpretation open to the viewer’s imagination. Viewing these works, the spectator seems to become enveloped, almost immersed in these paintings — all without frames, without delineation. Darker hues shimmer and fuse through bands of color in varying widths — speaking of nothing but stillness and silence. For Rothko, they are anecdotes of the spirit, which in my mind can be linked to the different movements of Shostakovich’s quartet, in which the two violins, viola and cello respond to each other either in harmony or opposition – all within the frame of the composition.

Schubert

Schubert

String Quartet No. 14 in D Minor, D. 810, “Death and the Maiden”

The Miro Quartet

Franz Schubert’s quartet in D-minor, written in 1824, is based on the earlier composition of the Schubert song ‘Der Tod und das Mädchen’ (Death and the Maiden) D 531/op. 7 No. 3, which he wrote in 1817, based on a poem by Matthias Claudius. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau’s rendition of the song is one of the most beautiful in recorded ‘Lieder’ history. The text is as follows:

| Das Mädchen: Vorrűber, ach, vorrűber! Geh, wilder Knochenmann! Ich bin noch jung, geh, Lieber! Und rűhre mich nicht an. | The Girl: Pass by, ah! Pass by, You savage skeleton! I am still young, go, my dear, And do not touch me. |

| Der Tod: Gib deine Hand, du schön und zart Gebild! Bin Freund und komme nicht zu strafen. Sei gutes Muts! Ich bin nicht wild, Sollst sanft in meinen Armen schlafen! | Death: Give me your hand, you dear and tender creature; I am a friend and do not come to punish. Be of good cheer! I am not savage, Gently you will sleep in my arms. |

Schubert’s quartet was given its name posthumously — with the second, somber movement taking its influence from the song. Here too, the mood of the composition is almost monothematic. A powerful opening establishes a pattern which runs throughout the work — the allegorical reference to the Maiden (agitated) and Death (reassuring, calming) passes from the major to minor keys — triplets and special rhythms agitate with ever-changing, colorful textures. Beautiful, melodic lines evoke a waltz-like atmosphere, but then lead into a final ‘tarantella’ — the frenzied dance associated with the effects of warding off the fatal bite of a spider — which ends abruptly, leading into silence and death.

Schubert’s quartet was given its name posthumously — with the second, somber movement taking its influence from the song. Here too, the mood of the composition is almost monothematic. A powerful opening establishes a pattern which runs throughout the work — the allegorical reference to the Maiden (agitated) and Death (reassuring, calming) passes from the major to minor keys — triplets and special rhythms agitate with ever-changing, colorful textures. Beautiful, melodic lines evoke a waltz-like atmosphere, but then lead into a final ‘tarantella’ — the frenzied dance associated with the effects of warding off the fatal bite of a spider — which ends abruptly, leading into silence and death.

Egon Schiele’s work ‘Death and the Maiden’ was painted in 1915, not long before Schiele’s untimely death from the Spanish Influenza, which had also taken his wife Edith a few days earlier. Schiele portrays himself as death, and his wife, Edith as the maiden — death has thus become personalized and the journey becomes a personal one as well – reminiscent of the ‘wanderer’ in Schubert’s Winterreise, which can be interpreted as Schubert’s own personal battle facing illness and death. Schiele shows the maiden seemingly taking comfort in the embrace, but Schiele, as death, seems terrified — his startled eyes, looking directly at the viewer, express the horror and fear — almost the reverse of Schubert’s song, but very close to the wanderer in the Winterreise, (The Winter’s Journey) — of someone who had lost all hope and is facing silence and death.

Egon Schiele’s work ‘Death and the Maiden’ was painted in 1915, not long before Schiele’s untimely death from the Spanish Influenza, which had also taken his wife Edith a few days earlier. Schiele portrays himself as death, and his wife, Edith as the maiden — death has thus become personalized and the journey becomes a personal one as well – reminiscent of the ‘wanderer’ in Schubert’s Winterreise, which can be interpreted as Schubert’s own personal battle facing illness and death. Schiele shows the maiden seemingly taking comfort in the embrace, but Schiele, as death, seems terrified — his startled eyes, looking directly at the viewer, express the horror and fear — almost the reverse of Schubert’s song, but very close to the wanderer in the Winterreise, (The Winter’s Journey) — of someone who had lost all hope and is facing silence and death.

Shostakovich’s and Schubert’s compositions and Rothko’s and Schiele’s paintings are able to convey the inherent spirituality of these extraordinary works – still speaking to us, the listener and viewer – and thus making these works eternal.