Lang Lang

Credit: http://www.rai5.rai.it/

The concert hall is like the theatre, and the performer the actor on the stage. And for the audience, a concert is both a visual and aural experience – we “listen” with eyes as well as ears. Today audiences are likely to be as much concerned with what they see in performance as what they hear. But surely the sound of the music should be enough? Sadly, this isn’t the case and what the performer looks like, how they behave on stage, and what they wear has almost as much, if not more in some instances, bearing on the entire performance.

It shouldn’t matter what performers look like, but in our visually-aware times it does. Because isn’t it nicer to enjoy music played by performers who are easy on the eye as well as the ear? Of course we want performers to be attractive and attractively-attired. On one level, it indicates that the performance is an “occasion” and concert attire “identifies” the performer for the audience. It is a “uniform”, a means of differentiating the performer from audience and defining their role for them. Some performers prefer to go to the other extreme and appear in casual clothing which they feel better connects them with the audience by making them appear “normal”, and that it helps break down misconceptions about classical music being “elitist” or “inaccessible”.

Once we have got over what performers are wearing, there is a whole other area – that of movement and gesture. Performers use body language to convey the “story” of the music, expressive elements, drama and their own involvement in the music. This is an area of performance which, for me, has far more importance over the performer’s clothing. I believe gesture should serve the music, not obscure it. We have all witnessed exaggerated gestures at concerts – extravagant hand and arm waving, swaying across the keyboard, and gurning as if one has extreme indigestion – and now and then we have wondered what is the point of such pianistic gesticulation.

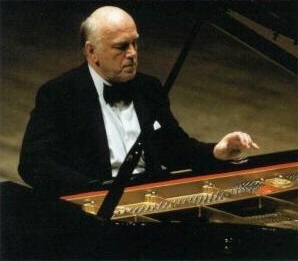

Sviatoslav Richter

Credit: http://www.luventicus.org/

The physical movements and gestures of the performer not only influence the character and quality of sound but also enhance the dramatic content of the work and “explain” the music to the listener. Music is emotional and expressive – even the most mannered passages of Bach are rich in expression – and the performer’s physical gestures communicate the content of the music being played. Sometimes, these gestures can seem extreme, and when the performer’s gestures get in the way of the music or have no connection to the ‘story’ in the music, it can be frustrating or impossible to watch. But at other times, with the right gestures, the performance is magically enhanced and heightened – for both listener and performer.

Gesture should always serve the music – not only in terms of the sound being produced but also in guiding the audience through the narrative of the music. At the end a performer may fling their hands away from the keyboard and the audience will know that the performance has ended and will take that as the cue to applaud. Or a performer may choose to allow their hands to remain on the keyboard, withdrawing them slowly to allow the memory of the sounds to continue to resonate with the listeners. The audience reads these gestures and will (hopefully) know not to applaud immediately.

The spectrum of gesture in piano playing is very broad, from almost complete concentrated stillness at the piano (Marc-André Hamelin, Stephen Hough) to exaggerated flamboyance bordering on the ridiculous. Sensitive performers will adjust their gestures according to the character and mood of the music. I have noticed a trend amongst certain younger performers to use gestures which seem unnatural and contrived, as if they have been “given” these gestures by teachers or mentors, or are trying to imitate another performer. Turn off the sound on the YouTube clip below and consider whether these performers’ movements have any value without the music?

By contrast, the late great Russian pianist Sviatoslav Richter liked to perform in darkness, with only a small lamp illuminating the music stand. He felt that this setting helped the audience focus on the music being performed, rather than on extraneous and irrelevant matters such as the performer’s grimaces and gestures. “What’s the point of watching a pianist’s hands or face, when they only express the efforts being expended on the piece?” he said. And at a concert hall in Bremen, Germany, concerts take place in complete darkness, owing to the venue’s design which avoids light leakage, allowing the audience a very special aural experience without any visual distractions.