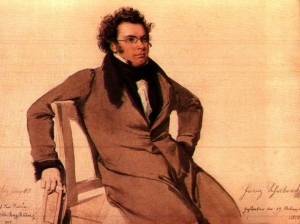

Schubert

Credit: Wikipedia

Brendel plays Impromptu in A flat, Op 90/4

Schubert famously and tragically died young, at 31, possibly from complications arising from syphilis, yet in his short life he, like Mozart, Chopin and Mendelssohn, produced a phenomenal amount of work, not all of it complete, much of it sublimely beautiful, absorbing and endlessly fascinating. When considering the piano music which came post-Winterreise – the two sets of Impromptus, the D946 Klavierstucke, the late piano sonatas, we may be tempted to label them “mature” works, yet they were written by a man who by present-day standards was “young”.

The Opus 90 Impromptus are works born out of the tumult of Winterreise, and are perhaps best tackled by a musician who has lived with the music for a long time.

They are often performed as a set, though sometimes a single Impromptu will be offered in a programme, or as an encore (Schubert himself told his publishers that the works could be issued singly or in a set), and the four pieces seem to present a kind of journey (‘Reise’), both musical and metaphorical, when considered together.

The first of the Opus 90, in C minor, opens with a bare G octave, and the ensuing lonely dotted melody sets the tone of the whole piece. In one recording I have, the work freezes, calling to mind the exiled fremdling (traveller) of songs such as ‘Gute Nacht’, from Winterreise. The chill never really thaws as the music continually struggles to break free of that portentous, restraining G: it never truly succeeds, despite the lyrical and nostalgic A-flat sections. The warm, major key offers little real solace, as the harmonic progressions constantly drag the ear away from the resolution it craves, and any pleasant recollections are quickly forgotten by the return of the chilling tread of the opening motif.

Brendel

Credit: http://intermezzo.typepad.com/

The streaming, scalic figures of the opening require wrist flexibility and suppleness, the wrist acting as a shock absorber to help shape the phrasing here. While the music is marked ‘Allegro’, there needs to be some give-and-take within the phrases, signaling shifts in mood and tone. There are measures of great charm and true Schubertian “prettiness”, but these are quickly offset by the darker, minor sections. This is not a moto perpetuo exercise in the manner of Czerny: it is an Impromptu, and by its very name it suggests romanticism rather than rigour.

The Trio suggests a rough, bohemian waltz, with a figure of widely-spaced bare octaves, and stamping off-beat accented triplets, alternating with a division of the beat into quavers, a stark contrast to the flowing triplets of the earlier sections. There are some moments of great melodic beauty and poignancy here, but the roughness and tension are never really smoothed, while a sobbing, repeated triplet figure acts as a bridge, leading us back to the opening material. The pieces ends, emphatically, in the minor key, signalling once again the confusion of Schubert’s lonely traveller.

The third Impromptu, in G-flat major, is probably the best-loved of the set, with its serene, nocturne-like melody redolent of Schubert’s Ave Maria, and its fluttering harp-like broken chords, which soothe after the torment of the previous piece. There are storms – bass trills, and a shadowy, frequently-modulating middle section – before the music returns to the same flowing calmness of the opening.

And so to my favourite, No. 4, in A-flat, and here at last all the uncertain tonalities of the preceding movements find a home. This is not prefigured at the outset: the piece opens in A-flat minor, though it is written in the major, with accidentals, and the harmonic ambiguity lingers until bar 31, when the graceful, cascading semiquaver figure is at last heard in A-flat major, beneath which the left hand has a fragile, ‘cello-like melody. At the centre of the piece is a lyrical Trio reminiscent of Schubert’s ‘Wanderer’ fantasy, after which the sense of alienation and tension from the earlier Impromptus is swept aside by the gradual acceleration of all the elements and the home key, A flat, becomes fully dominant, while a life-affirming dance-like figure takes over in the bass. The final cadence is an emphatic A-flat major descent and two forceful closing chords. Home at last.

It may be fanciful to assign such complex musical and thematic considerations to these pieces, but play or hear them as a set, and I think the sense of a journey is evident, if only in the progressive tonalities of each piece. In any event, these are poetic, timeless, and very personal works, which display a gravity and intensity far beyond the typical nineteenth-century drawing room Albumblatt or klavierstück.