Aida 2017: Francesco Meli (Radamès), Anna Netrebko (Aida)

© Salzburger Festspiele / Monika Rittershaus

Mozart’s Clemenza di Tito, directed by Peter Sellars, was widely praised for the racial and political exploration and the American director’s unmistakable commentary on religious fundamentalism.

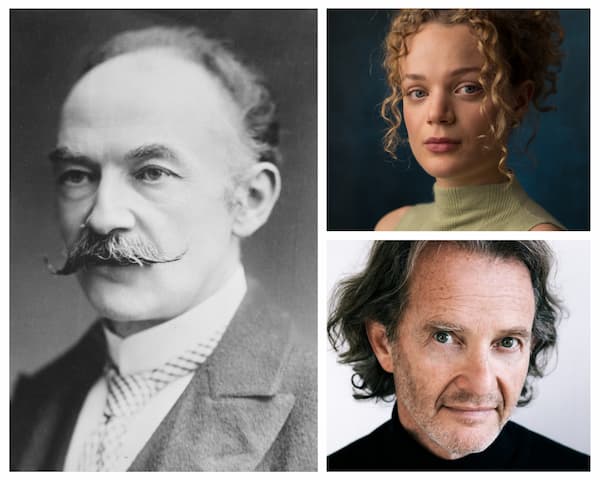

But the much anticipated production of Giuseppe Verdi’s Aida, directed by exiled Iranian visual artist Shirin Neshat and starring Russian uber-diva Anna Netrebko was possibly designed to catapult Salzburg to true global relevance.

Netrebko attacked the role with her customary professionalism. She demonstrated her stunning grasp of Italianate coloratura, with soaring and confident heights and knee buckling pianissimi. Her third act “Oh patria mia” was magnificently sensitive. Netrebko was vocally the princess, the passionate lover, the self sacrificing partner.

She was paired with tenor Francesco Meli – clearly a favorite counterpart – whose voice has matured since his Trovatore opposite the Russian diva two years ago. Though he could use an extra caliber or two of dramatic vocal strength, he portrayed a believable and empathetic Radames, starting with a restrained and nearly lyrical “Celeste Aida”. He cautiously unfolded his beautiful tenor over the next three acts, only occasionally showing signs of vocal overstretch.

Amneris, the jealous Egyptian princess in love with Radames, was ably sung by the Russian Ekaterina Semenchuk. While it took her time to warm up, she ultimately proved convincing. Luca Salsi was an impactful Amonasro, showing Italianate timbre of the finest sort and true dramatic drive. In the bit parts the young Benedetta Torre shined through as the High Priestess.

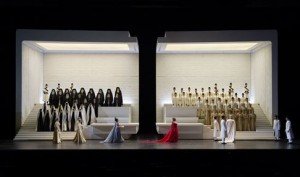

Aida 2017: Anna Netrebko (Aida), Ekaterina Semenchuk (Amneris), Roberto Tagliavini (The King), Concert Association of the Vienna State Opera Chorus, Supernumeraries

© Salzburger Festspiele / Monika Rittershaus

The much vaunted choice of Shirin Neshat, however, proved a miscalculation. The first time opera director who admittedly knows little about opera, though is a very fine visual artist in other fields, struggled to make sense of Aida. Her inexperience in matters operatic was painfully obvious in the static direction that made poor use of the stage and allowed the singers little gestural freedom. The result was wooden and often dull, forcing the singers into unfashionable park-and-bark positions, denying them movements and ultimately feeling.

The triumph march was hardly triumphal and the direction seemed to forget to supply any marchers, showing only a poorly rehearsed dance group and a neighborhood police squadron-sized Egyptian army. The slaves were barely more numerous, leaving the Egyptian dignitaries on the grandstand looking understandably bored.

The stage set consisting of two large white cubes did them no favors, looking like a high school auditorium designed by Swiss minimalist architect Peter Zumthor with generous use of white brick and cement. Like a victorious nation this did not look. The confused costume choices didn’t help, with the males looking like Coptic priests and the women like nuns of an undefinable order.

While the triumph march was underpopulated, the last act judgment scene was overpopulated. A seemingly interminable procession of judges, beards and hats included but now with red robes, filed into the back of the white cube. With so many judges it’s amazing they reached the quick quorum on Radames’ guilt. Occasional projections of unemotional judges added nothing at all.

Aida 2017: Ekaterina Semenchuk (Amneris), Concert Association of the Vienna State Opera Chorus

© Salzburger Festspiele / Monika Rittershaus

Shirin’s enthusiasm to direct further operas might be limited after the intense boos of opening night. One cannot help but think this remarkable artist was talked into this tricky assignment and then given insufficient support to help her succeed.

Regardless, Hinterhaeuser did deliver on his promise of power. German Chancellor Angela Merkel quietly sat in the audience, the powerful sponsors were out in full strength, and Netrebko showed the true extent of her star power. Her performances are hopelessly sold out with ticket requests exceeding seven times the available seats.

Performance attended: August 5, 2017