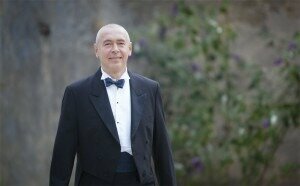

Credit: http://www.ivopogorelich.com/

And so it seems I should have enjoyed the Croatian pianist Ivo Pogorelich’s return recital at the Hong Kong Cultural Centre last night, since this artist clearly has bucket loads of personality and limitless passion. However, his idiosyncratic style comes in the guise of mood swings akin to those exhibited by a schizophrenic, which actually might have worked in the Schumann, with the struggle between the impulsive Florestan and the dreamy Eusebius characters, but more on this later.

From the start, when he signalled to his page-turner to sit on a piano stool instead of a chair with a back, to the end of the recital when he skillfully kicked his piano stool underneath the piano to inform the audience that there would be no encores – not to mention the way he tossed his scores onto the floor – I felt a little ill at ease.

The opening tritones (also known as the Devil’s interval) of Liszt’s Après une lecture de Dante surely sounded like the wicked mockery of the Devil, but as the piece went on, this overwhelming heaviness in sound became over-persistent, and as a result, the Steinway piano sounded more like a bad Kawai. The melodic lines were not sustained and neither was the momentum – Mr Pogorelich had a tendency to make rubatos whenever he felt like it – and the piece lost its architectural shape and form and did not seem to make sense musically. The more reflective and sensitive passages, instead of emerging from nowhere, appeared too matter-of-factly and in-your-face.

Credit: http://www.kamane.lt/

This weird interpretation of tempo seemed to be a recurrent theme, as Mr Pogorelich’s first movement of Stravinsky’s Three Movements from Petrushka also seemed ‘lost in translation’. The opening energetic rhythmic figures were infused so liberally with random rubatos that I felt the essence of the music – a dance – was lost. The other two movements were less odd, but again, his tonal palette lacked colour and the bravura passages sounded rather laboured.

The Brahms Paganini Variations fared better. Thanks to the structure of the work, we were able to detect a sense of momentum, which was unfortunately lacking in the other works. Each variation was short, sweet, and solid. I would have perhaps enjoyed a richer orchestral sonority as opposed to his mechanical one-dimensional approach.

Mr Pogorelich chose a demanding programme, and while some of the audience clearly enjoyed his deafening sounds and impressive gestures, I wonder whether he is still technically fit to play these pieces. Were the unconventional tempi chosen to compensate for his reduced physical prowess? Could it be that the pianist is going through a mid-life crisis yet wants to convince the world that he is still a young, able athlete? The more pressing question is, if an unknown pianist played in exactly the same way, would the performance be as well-received and would he/she have such a thriving career?