Recognised as one of Gioachino Rossini’s most brilliant and innovative comedies, Il Turco in Italia (The Turk in Italy) is a laugh-out-loud opera buffa, full of energetic and buoyant music. With a libretto by Felice Romani, the work first sounded at La Scala in Milan on 14 August 1814. It was not considered particularly successful at its premiere and received only token performances in the first quarter of the 19th century. However, it was successfully revived in Rome in 1950 with Maria Callas taking the leading role.

Gioacchino Rossini: Il Turco in Italia, “Overture”

The Plot: Act 1

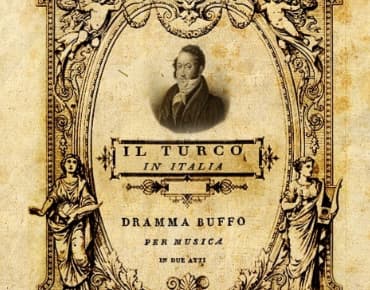

The young Gioachino Rossini

The poet Prosdocimo (bass) has a writer’s block and is in search of a subject for a comedy drawn from real life. At a gipsy camp near Naples he meets Zaida (soprano) who, as a slave girl in the Erzèrum harem, once loved the prince Selim (bass) but was forced to flee after slanders by jealous rivals had led Selim to sentence her to death. Zaida is still in love with Selim, and she now lives unhappily in hiding, longing to be reunited with him. Prosdocimo promises to help her.

Gioacchino Rossini: Il Turco in Italia, “Serva…servo”

Zaida tells the poet that a Turkish prince will soon arrive and that the news of her continued fidelity to Selim can then be sent to Turkey. In the bright sunlight of opera buffy, the handsome Turkish prince arrives in Naples looking for amorous adventures. In fact, the prince is Selim himself. In no time at all, he meets the vivacious young Italian wife Fiorilla (soprano), who is married to the frustrated and grumpy Don Geronio (bass). Fiorilla sings of the delights of her ever-changing lovers, when Selim arrives.

Gioacchino Rossini: Il Turco in Italia, “Siete Turchi, von vi credo”

Selim immediately rushes for Fiorilla, who feels an instant attraction to the handsome stranger. She invites him home for coffee, much to the horror of both her husband and her lover Don Narciso (tenor). The poet watches the unfolding events with great delight. The flirting of Selim and Fiorilla, the anger of Geronio and Narciso, the confusion when Selim and Zaida finally meet and recognise one another, and specifically when they are discovered in an affectionate embrace. Prosdocimo now realises that he has unwittingly assembled the perfect cast for his comedy.

Gioacchino Rossini: Il Turco in Italia, “No, mia vita, mio Tesoro”

The Plot: Act 2

Rossini’s Il Turco in Italia, with Maria Callas taking the leading role, 1954

Selim is determined to have Fiorilla, and he offers to buy her from her husband. Geronio is horrified, he refuses and the two men almost come to blows. Feeling left out, Fiorilla has decided that it is time for Selim to choose between herself and Zaida. Selim seems unsure, so Fiorilla hopes that a masked ball will give them the opportunity to slip away once and for all.

Gioacchino Rossini: Il Turco in Italia, “D’un bell’uso in Turchia”

At this stage Prosdocimo gets involved and warns Geronio of the plot. He suggests that he and Zaida should wear the same costumes as Selim and Fiorilla in order to confuse them. As expected, things don’t go exactly to plan as Narciso shows up in the same costume as Selim. The four young lovers all successfully make their exits, not necessarily with the correct partners, and Geronio is left alone and furious.

Gioacchino Rossini: Il Turco in Italia, “Oh, guardate che accidente”

The confusion of the ball has reunited Selim and Zaida, and they plan to return to Turkey together. While they get ready to depart, Geronio and Fiorilla must negotiate a tricky reconciliation. When her husband locks the door against her, she realises the errors of her ways. In the end Geronio does forgive her, and both couples celebrate their future lives together. Last but not least, Prosdocimo is overjoyed as he has gotten his happy end.

Gioacchino Rossini: Il Turco in Italia, “Non si dà follia Maggiore”

The Music

Rossini’s Il Turco in Italia cover page

Rossini was only 22 when he composed Il turco in Italia, but he responds to the buffoonery of the plot with an inspired and constantly amusing score. Il turco is essentially an ensemble opera with only Fiorella having an important series of solo arias. The solo numbers mainly occur in Act 2, and even Fiorilla, “cavilling hussy and sophisticated woman of the words, is characterized more by her role-playing in ensembles than by either of her cavatinas.”

Rossini’s Il Turco in Italia, Teatro Real de Madrid, 2023

The poet has no arias or duets and only sings in recitatives, and in the Act 1 trio and the ensemble within the Act 1 finale. A scholar writes, “the opera is dominated by ensembles and conversations, etched in with the most delicate strokes, in a style entirely appropriate to the drawing-room chatter of a piece full of double meanings, hypocrisy, smothered anger, forced smiles, and asides through clenched teeth.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter