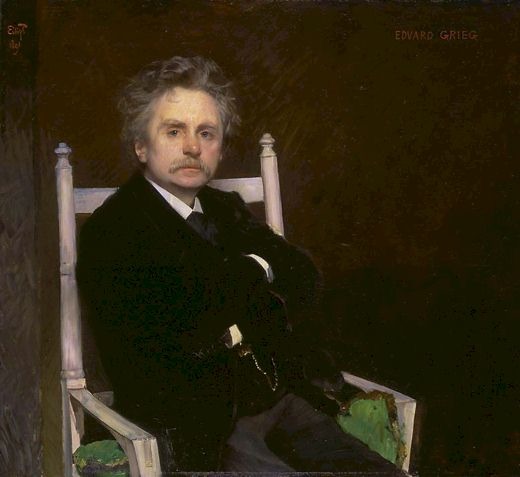

Edvard Grieg

Piano Sonata in E Minor, Op. 7

II. Andante molto

Edvard Hagerup Grieg (1843-1907) is widely acknowledged as a central figure in the emergence of a distinctively Scandinavian tone in nineteenth century music. Even the composer, in his own words, was “determined to create a national form of music, which could give the Norwegian people an identity.” I have always had some reservations about Grieg’s statement. Was it not the spirit of the people of Norway that gave musical expression in and through Grieg, rather than Grieg being a representative of his nation? A noted scholar and philosopher has rightfully suggested that, “the distinction between national style as a musical fact and nationalism as a creed imposed on music from without is far too crude to be an accurate reflection of the historical and aesthetic reality.” I recently came across a wonderful interpretation of Grieg’s Piano Sonata in E minor, Op. 7 by the young Russian pianist Boris Giltburg. In his liner notes Boris writes, [in this Sonata] “Grieg has managed to capture the essence of Nordic nature and landscape.” To me, this is a rather surprising statement as the music brims with the influences — not merely musical — Grieg had gathered and learned at the Leipzig Conservatory, then under the direction of Ignaz Moscheles.

Boris Giltburg

So when Boris talks about Nordic landscapes and nature in Grieg’s juvenile piano sonata — a connection that even Grieg could not claim for this work — he is imagining a set of assumed or inherited symbolisms and attributes. Boris, it seems, is thinking of Grieg’s Sonata retrospectively as the individual expression of a collective Norwegian musical identity. Fascinatingly, however, his musical interpretation intuitively addresses the actual musical aspects found in the score, including the opening Schumanesque Cipher, the figurations and turns of harmony in direct debt to Chopin, and the highly sophisticated yet deceptively simplistic melodic construction of Mendelssohn.

And that is precisely why I do like his interpretation. Maturity will almost certainly bridge the divide between talking about music and making it; for now we must simply acknowledge that Boris’s musical instincts are right on the money!

Official Website